Culture Vulture: Back to Laramie: Moises Kaufman’s Epilogue and Judy Shepard’s Memoir

By Helen Epstein

I saw “The Laramie Project Epilogue” at the Barrington Stage Company in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, one of a reported 150 venues around the world where staged readings took place this week, the eleventh anniversary of what has become perhaps the most famous hate crime in the world. In October of 1998, twenty-one year old Matthew Shepard, a gay student at the University of Wyoming, was kidnapped, badly beaten, and tied to a fence on the outskirts of Laramie, Wyoming where he went into a coma from which he never recovered.

I saw “The Laramie Project Epilogue” at the Barrington Stage Company in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, one of a reported 150 venues around the world where staged readings took place this week, the eleventh anniversary of what has become perhaps the most famous hate crime in the world. In October of 1998, twenty-one year old Matthew Shepard, a gay student at the University of Wyoming, was kidnapped, badly beaten, and tied to a fence on the outskirts of Laramie, Wyoming where he went into a coma from which he never recovered.

There are 18 to 20 reported gay homicides in the United States a year, director Moises Kaufman’s points out in his production notes, but the circumstances of this one brought together many contemporary themes that struck him as perfect for a work of theater. Like Truman Capote, living in New York City but riveted by the murder of the Clutter family in Holcomb, Kansas in 1959, Kaufman and eleven actors from the New-York-based Tectonic Theater Project began a series of visits to Laramie, Wyoming.

Instead of one weird outsider journalist walking up to strangers and asking for an interview in Kansas that is so memorably re-enacted in two movies about Capote, this time eleven outsiders with tape recorders descend on Laramie, each driven by his or her own interests. One looks up Matthew’s friends; others, the murderer Aaron McKinney and his accomplice Russell Henderson. Some are interested in talking with students and professors in the university community; others with local law enforcement officials, cowboys, farmers, lesbians and gays. Some actors attend the court trial and their own reactions (recorded in journals) become part of the play, along with edited selections from over 200 interviews and parts of the transcript. The only people the company decided not to interview were members of Matthew’s immediate family.

“The Laramie Project” premiered in Denver in 2000. Then it moved to New York where it garnered some stellar reviews, not least from picky critic John Simon who termed it “Nothing short of stunning … A theatrical event not to be missed.” In 2002, the Sundance Film Festival screened the film version, directed by Kaufman and featuring some TTP actors along with several Hollywood stars.

Like “The Diary of Anne Frank” and “The Vagina Monologues,” “The Laramie Project” became far more than a piece of theater. Widely read and produced at high schools, religious institutions and universities across the country, it has become a teaching tool, a vehicle for raising awareness of the consequences of bigotry, and a rallying point for civil rights for gay and transgendered people. As a theater piece, it evokes “Our Town” and “Spoon River Anthology” as well as courtroom drama and earlier interview-generated works like “A Chorus Line” and Anna Deavere Smith’s one-woman shows. Like her current piece on life insurance, “Let Me Down Easy,” “The Laramie Project” interacts with current events in Washington.

After a decade of stalling, the House last week voted 281 to 146 to pass Bill HR 1913, the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, named after Matthew and the African-American Texan dragged to his death behind a pickup truck that same year. If adopted by the Senate, this bill would expand the definition of violent federal hate crimes to those committed because of a victim’s sexual orientation.

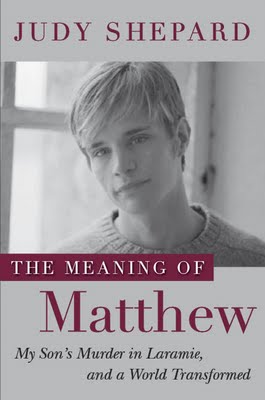

After a decade too, Hudson Street Press last month published Judy Shepard’s “The Meaning of Matthew: My Son’s Murder in Laramie and a World Transformed.” The book is not literary nor probing enough to qualify as a great memoir: Judy Shepard writes that “soul searching” for her is a private affair — not a promising personal quality for writing in this genre. But “The Meaning of Matthew” is literature of witness, so compelling a story that it trumps her proclivities and skills. Though laconic and, at times, self-protective (“I don’t know a lot of the details …” recurs in the narrative), it’s an important, affecting, Mom’s account of the short life Matthew had “before he was tied to that fence.”

Mrs. Shepard briefly describes growing up as the daughter of the postmaster in small town Wyoming, her marriage to fellow westerner Dennis Shepard and first pregnancy: her growing awareness of her smaller-than-average, blond, sensitive, theater-loving older son’s homosexuality; the family’s move to Saudi Arabia after the oil industry falters in Wyoming and Dennis takes a job with Aramco; their reluctant decision to send Matthew to boarding school in Switzerland. She tells us that because of her husband’s frequent absences, she and Matthew were extraordinarily close and recounts Matthew’s interest in Dolly Parton, as well as international relations and the problems of his friends and classmates.

In what turns out to be a horrific precursor to the events in Laramie, she describes getting a telephone call from Matthew in Marrakech where he is visiting with other students from his school. Her son tells her he was attacked and raped by three adult men who took his shirt and shoes, then fled into the night. Although he reported the attack and was well-treated by the Moroccan police, Matthew never, in his mother’s view, recovered from that rape. “After the attack,” she writes, “he seemed to assume the attitude of a beaten-down victim: His posture was slumped, his gait became more of a shuffle, and he purposely chose to wear clothes that were way too big for him, as if he wanted to hide in the fabric…. By far the most disturbing episodes of the aftermath were the nightmares…”

Although the Shepards try to find Matthew a therapist to address the trauma, what goes on in the Shepard family in the immediate aftermath of the rape is skipped. It’s unclear how the parents and younger sibling dealt with their son’s rape, whether they talked about it with Matthew, how long he actually was in therapy (in Switzerland? Saudi Arabia?) before high school graduation and going off to college in North Carolina.

These omissions are characteristic of the author’s self-acknowledged aversion to painful material as well as most emotional and psychological matters and are clear examples of the difference between content and writing. Given the dimensions of the tragedy, it seems callous to point out that Mrs. Shepard is a reluctant memoirist, disinclined to deeply probe “the meaning of Matthew.”

But the fact is that her memoir is more of a distanced narration of events, including her family’s learning of their son’s murder, the trial, the issues and the media circus that followed. It aims to correct inaccuracies about the family that crept into media coverage and to bring attention to the work of the Matthew Shepard Foundation that Judy and Dennis Shepard co-founded to promote tolerance and support for human rights regardless of sexual orientation.

But the fact is that her memoir is more of a distanced narration of events, including her family’s learning of their son’s murder, the trial, the issues and the media circus that followed. It aims to correct inaccuracies about the family that crept into media coverage and to bring attention to the work of the Matthew Shepard Foundation that Judy and Dennis Shepard co-founded to promote tolerance and support for human rights regardless of sexual orientation.

The media, old and new, left and right, have been abuzz with reaction to Shepard’s murder and its significance for years, especially since the ABC program “20/20” did a piece five years after the fact representing the murderers as methamphetamine-crazed robbers rather than gay-haters. The Right was quick to embrace the “20/20” version. Congresswoman Virginia Foxx of North Carolina claimed last spring that Shepard’s horrific murder was a “hoax.” “We know that that young man was killed in the commitment of a robbery. It wasn’t because he was gay.” There are many more byzantine and wacky explanations of the murder up on the net but I won’t waste space by reprinting them here.

Dr. Judith Herman, in her classic book, Trauma and Recovery writes about the difficulty both individuals and societies have in retaining accurate memory of unspeakable events: “In the absence of strong political movements for human rights, the active process of bearing witness inevitably gives way to the active process of forgetting. Repression, dissociation, and denial are phenomena of social as well as individual consciousness.”

Given this very large context, “The Epilogue to the Laramie Project” isn’t just an update but a work of artistic witness. The reading I saw in Pittsfield was absorbing but only indicated the work’s performance potential. In the script, Kaufman and his company revisit Laramie a decade later to examine how both the passage of time and deliberate revisionism combine to eradicate the memory of what happened there. The fence to which Matthew Shepard was tied, they find, is now gone. Too many memorials, too many tourists for the owner of the land to deal with. The Fireside bar where Matthew Shepard and his murderer met has been sold, its name changed.

There is a bench dedicated to Matthew at the University of Wyoming (“Beloved Son, Brother and Fried; He continues to make a difference; Peace be with him and all who sit here” ) but new undergraduates interviewed by the TTP have only a vague idea of who Matthew Shepard was.

The company revisited many of their original interviews –- Father Roger, who urges them to try to interview the murderers and discover what Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson have to teach us; University Professor Catherine Connolly, who was galvanized to run for the Wyoming State Legislature where she has become the first openly gay member and Laramie’s chief law enforcement officer Dave O’Malley who in the aftermath of Matthew’s murder made a 180 degree change, went to D.C. to lobby for hate crime legislation and says in the Epilogue, “What I had been doing all my life was precluding a fine group of individuals from my friendship.”

On the other hand, there are people in Laramie quoted as saying “I do think it’s time to let the boy go” and, as an editorial in the “Laramie Boomerang,” the town newspaper, put it: “Laramie is a community – not a project.” A gay man who found his significant other during the aftermath of the murder and lives in the relative safety of the university community, says: “Finding your safe pocket is what we gay people do – not just in Laramie but everywhere.”

Attending a reading of “Laramie:The Epilogue” and reading Judy Shepard’s memoir raise far more questions than answers. They are of a nature more conducive to the long and reflective process of writing a book rather than a blog post: questions about art, personal and social psychology, law, revisionism, memory, history, the relative strengths of journalism, film, or theater in representing a momentous event as well as who gets to interpret its meaning.

These questions are overshadowed by a far more pressing reality: Senator Carl Levin has reported that the FBI recorded reports of more than 77,000 hate crimes from 1998 through 2007 and that crimes based on sexual orientation were on an upward trend.

Helen Epstein is the author of “Joe Papp: An American Life,” “Children of the Holocaust” and a new book of essays on memoir in French titled “Ecrire La Vie.”