Book Commentary: Alberto Moravia’s 100th Birthday — A Giant Dissed?

By Bill Marx

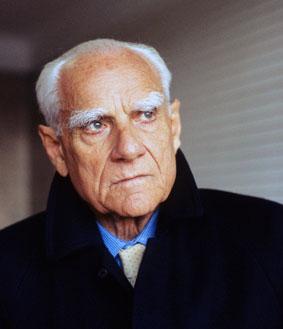

Alberto Moravia — One of the finest Italian novelists of 20th century.

A major Italian novelist with a worldwide reputation, Alberto Moravia, would have been 100 this year, but even in his homeland the parties are halfhearted. We should be breaking out the champagne and discovering this still subversive realist.

The excellent Literary Saloon recently sent me to an article in Il velino that rounds up a bunch of Italian literary scholars to explain why Alberto Moravia, once considered one of Italy’s greatest novelists, has so little contemporary appeal. Moravia’s homeland is celebrating his centenary this year (November 28 1907 – September 26 1990), but the parties are, alas, halfhearted. He should be toasted in Italy and around the world with gusto — Moravia is an unusual visionary, a wry subversive of a realist who, at his best, uses fiction to dramatize how the imagination can serve as a means to discover reality.

Predictably, the critical responses for the Italian downturn are not very illuminating: the writer’s anti-bourgeois slant and mordant pessimism have dated, literary tastes change, his weaker books are falling by the wayside. Still, Moravia is still a force to be reckoned with via lauded film versions of his novels, which range from Luigi Zampa’s The Woman of Rome to Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt, Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist, and Cédric Kahn’s L’Ennui.

In truth, Moravia already looked like an antique, at least to superficial readers and critics, back in the 1960s. His deadpan approach to erotic fantasies was considered tasteful rather than shocking; his focus (some would say obsession) on detailing the ‘male gaze’ was condemned by feminists as macho patronizing. His response to political correctness was 1971’s The Two of Us, a zany battle between a man and his feisty penis that won Moravia few friends and is, no surprise, out of print in English. Fans of Philip Roth’s The Breast should take note.

Before World War II, Moravia’s novels blended schematic plotting and forceful character delineation with a lucid – rather than difficult – brand of modernism. His analysis of fascist domination and middle class alienation was meticulous; his exploitation of Freud more ambiguous and/or satiric than he was (and is) given credit for. After the end of the Cold War, Moravia was dismissed as a musty relic, even though by the 1950s, in novels such as Contempt and Boredom, he had turned to more meta-fictional narrative techniques, dunking his hapless control freaks in a maelstrom of voyeurism. Now, in an age that likes it irony earnest, that playful self-consciousness works against him.

Back in 2000 I wrote an appreciation for the Boston Review of Steerforth Press’s gallant attempt to put Moravia back into print. The lineup included a fine new translation of his first novel, 1929’s The Time of Indifference, along with 1947’s The Woman of Rome, 1951’s The Conformist, and 1990’s Life of Moravia. 1954’s Contempt and 1960’s Boredom are available from New York Review Press. In a sense, Moravia is lucky – most of his major novels are available in English translation. But his charm ran out in the centennial year, given that the only new version of Moravia to appear, Conjugal Love, is a fine version of one of his minor efforts. Few readers will be inspired after reading it to tackle his other works. I would have preferred a selection of his finest short stories, since none of his collections are currently in print.

A bigger problem is that Moravia has found no champions. Outside of Italy, his novels have garnered little serious attention from today’s critics, which partly explains why his reputation around the world, not just at home, has faded. (Is there any connection with the fate of Moravia’s fiction and the continued neglect of Luigi Pirandello’s novels and short stories?)

Moravia’s diagnostic approach to the novel presents a pleasurable and provocative alternative to current tastes and prejudices. I tried to put my finger on why he is so good in the Boston Review:

Moravia is genuinely obsessed with the regularity we build around ourselves, the malevolent hydraulics of the psyche. What makes this fixation on fixation so compelling is that, with each return to his topic, Moravia delves deeper into the ideas shaping his characters’ spiritual and emotional paralysis. Moravia builds his narratives out of a limited number of primal situations; his figures examine, with skepticism and dogged determination, the reasoning that underlies their compulsion toward an imprisoning fantasy.

In other words, Moravia thinks art escapes the mechanical by accepting that it is more than a little mechanical itself. In the Life of Moravia (a collection of interviews with the author), the writer presents us with his unusual version of James Joyce’s epiphany, which he calls “illumination.” It is “a rational operation of dizzying speed. If you have a fan at home, and you turn it on, at a certain point you won’t see the blades anymore, you’ll see something of a blur. Now, illumination in reality is a fantastic acceleration of rationality.” Unlike many contemporary writers, who wall off thought from the imagination, Moravia sees reason serving as a necessary, though makeshift, bridge between our internal fabrications and a harsh reality.

In his essay collection Man as an End, Moravia argues that the modern novel should be revelatory rather than didactic. Fiction must concern itself with “the appearance of re-establishing the language of reason which is universal in its own right, and hence of re-establishing a relationship of some kind between narrator and reality.” For Moravia, imagination doesn’t replace reason. But fiction has the potential to reconnect reason with reality. The writer’s protagonists dramatize this possibility: they are self-involved, troubled dreamers wielding therapeutic scalpels on themselves. Moravia’s novels offer the serious pleasures of the diagnostic: the hope is that, by exposing forms of unreason, fiction will encourage more sophisticated, yet impulsive, understandings of the world.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: -Jean-Luc-Godard, -the-conformist, Books, Italy, alberto-moravia, bernardo-bertolucci, contempt, critics, italian-literature, modern-fiction