September Short Fuses — Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, television, film, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Classical Music

An opera need not be grand. It can be short and use modest forces, as I have noted here in regard to recent chamber operas by Jonathan Berger, Marti Epstein, Eric Nathan, and Scott Wheeler. Well, here’s another: A Dill Pickle, composed by Clark University music professor Matt Malsky and based on a famously laconic 1917 story by Katherine Mansfield.

Malsky’s 52-minute one-acter requires two singers, a violinist, a’violist, and a cellist. (Malsky discusses the opera in another short video.) The opera takes place in an English café around 1914. A woman (named Vera) chances upon a man (unnamed) with whom she was romantically involved six years earlier. He dominates the conversation, and we hear her thoughts in lengthy asides that rephrase passages that Mansfield had entrusted to a narrator. We come to understand why Vera needed to break with this braggart but how disappointing her life has been since she wrote him a farewell letter (which he tactlessly mentions).

Malsky sets the characters’ “audible” exchanges in a fascinatingly quirky manner: the words are declaimed at a steady, slowish pace, helping them be heard but also reflecting, especially, the man’s grandiosity. Vera’s private thoughts use more flexible rhythms and often flower into short melismatic passages (i.e., with three or more notes on a single syllable). The harmonic language also now becomes more complex, ungrounded, suggesting the pain of memory and loss.

The CD (and digital download) release is supplemented by an online libretto, but I recommend that you also watch the fascinating video version (online open-access). This “pocket opera” (my term) has legs! The singers and string players put it across effectively. I predict that the work will communicate to somewhat different effect with each new soprano and baritone that master it and share it with audiences eager for something new, different, and—quietly, wittily—devastating.

— Ralph P. Locke

Not every string quartet has a secret superpower. Then again, not every one of those is the Danish String Quartet, an ensemble whose affinity for all the corners of the standard canon is only matched by their enthusiasm for Nordic folk music.

Not every string quartet has a secret superpower. Then again, not every one of those is the Danish String Quartet, an ensemble whose affinity for all the corners of the standard canon is only matched by their enthusiasm for Nordic folk music.

The foursome’s latest release, Keel Road, expands a bit geographically on the last with some Celtic and Irish tunes added to the mix. But the performances are as fluent, comfortable, and spirited as anything on Wood Works and Last Leaf, the group’s prior forays into the genre.

There are no weak links among the album’s fourteen tracks, which range from the plaintive “Mabel Kelly” and hymn-like “Når mit Øye” to the lilting “Carrolans Quarrel with the Landlady,” robust “Kjølhalling,” and a deliriously charming medley of three tunes (“Marie Louise,” “The Chat,” and “Gale”), all in arrangements by members of the Quartet. In fact, the only major complaint to log against the effort is that, at 52 minutes, it’s a mite too brief (though, in fact, Keel Road is the longest installment of the Danish’s folk music discography to date).

No matter: this way you can listen to it twice. Certainly, the ensemble’s command of the repertoire – their feel for its style, total grasp of all of the musical elements, exuberant virtuosity, and sheer vigor – rewards repeated listening. More than that, they clearly love this music and the feeling is contagious.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

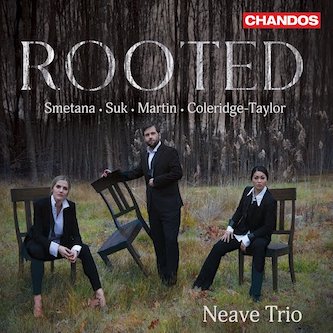

Rooted, the Neave Trio’s follow-up to their excellent last album, A Room of Her Own, is typically eclectic and varied. This time, though, the focus is a study of identity as understood by four composer who, today, stand on the fringes of the repertoire (if there).

Rooted, the Neave Trio’s follow-up to their excellent last album, A Room of Her Own, is typically eclectic and varied. This time, though, the focus is a study of identity as understood by four composer who, today, stand on the fringes of the repertoire (if there).

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s Five Negro Melodies sit at its center. Adapted by the composer from his solo-piano 24 Negro Folk Melodies, they considerably simplify some of the virtuosic keyboard writing of the original and lend his adaptations of Black spirituals and folk songs an enchanting glow. True, it may be a touch jarring to hear “Sometimes I feel like a motherless child” and “Didn’t my Lord deliver Daniel?” cast in Brahmsian garb – but when played as sensitively as by the Neaves, you can safely sit back and enjoy the ride.

Ditto for Josef Suk’s Petit Trio and Frank Martin’s rollicking Trio. The latter adapts a series of “popular Irish melodies,” lusty and vigorous ones in its outer thirds, and a mournfully keening set in the central Adagio. In it, the Neaves imbue the former with punch and bite, while the latter sings touchingly.

Their account of Suk’s charmer, too, highlights the score’s economy of ideas and structural rigor. Also its play of contrasts: the passionate first movement, coy second, and impish Vivace are all strongly etched.

Bedrich Smetana’s Piano Trio channels both its composer’s Czech nationalism and his grief at the death of his young daughter. The Neaves performance doesn’t quite overcome the music’s verbosity or capture its extremes with enough relish – see the Kavakos-Capuçon-Trifonov Trio at Verbier for that. But the shifts between expressive states in the first movement are smoothly done and the finale – with its clear play of rhythmic dissonance and jazz-like piano -tuplet turns – impress.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

Is there any composer whose music is more closely (or immediately) associated with the city of Berlin than Kurt Weill? Fittingly, three of his works are highlighted on Joana Mallwitz’s debut album (The Kurt Weill Album) with the Konzerthausorchester Berlin, which she leads. Ironically, though, only one of them was penned in Germany.

That one is Weill’s First Symphony, a curious, single-movement effort that, this time around, gets a somewhat Mahlerian treatment. Mallwitz isn’t afraid to take a spacious approach to parts of it (notably the closing Larghetto) and, surprisingly, that pays dividends. Her reading, notably, runs about five minutes longer than HK Gruber’s recent account; while that one’s directedness seemed to highlight the Symphony’s shortcomings, this one reveals a more compelling – though still a touch long-winded – musical argument. Go figure.

Equally inviting (and as vigorous as Gruber’s while a bit more animated than Lahav Shani’s) is Mallwitz’s take on the Symphony No. 2. The outer movements snap – the Konzerthausorchester’s delivery of the finale’s hairpin swells are thoroughly menacing – while the central Largo sings as a searingly ambiguous lament.

In between comes The Seven Deadly Sins, a “ballet chanté” Weill concocted with Bertold Brecht after leaving Nazi Germany for Paris in 1933. Katharine Mehlring brings just the right mix of brassiness, acid, and irony to the role of Anna, while Mallwitz, the Konzerthausorchester, and Anna’s “family” – sung by tenors Michael Porter and Simon Bode, baritone Michael Nagl, and bass-baritone Oliver Zwarg – inhabit their parts with commanding style: this is a brilliant, timely, and impressive performance in every way.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

Jazz

I heard On Their Shoulders: An Organ Tribute (MOCAT) before I looked up Matthew Whitaker’s biography. Even before I learned he is a once-in-a-generation talent, I could hear right away that this is music with life in it. It’s music with heart and vision.

I heard On Their Shoulders: An Organ Tribute (MOCAT) before I looked up Matthew Whitaker’s biography. Even before I learned he is a once-in-a-generation talent, I could hear right away that this is music with life in it. It’s music with heart and vision.

Whitaker, blind since birth, was a child prodigy with perfect pitch and an ear that lets him instantly reproduce virtually any music he hears. He’s been the subject of a documentary (Thrive), a feature on 60 Minutes, and the subject of countless interviews and media stories. He’s so inexplicably talented that he’s been studied by neuroscientists. His visual cortex has been taken over by more music processing.

One of the Whitaker’s compositions is titled, “Yessaah”! There are highlights galore in this album: the Latin percussion jam on “Happy Cause I’m Goin’ Home” sounds like opening a window on a spring day via groove established by Whitaker’s horn arrangement; the catchy modern jazz melody over traditional gospel chords on “Pilgrimage,” the minor-key exotica of “In the Key of the Universe,” the dramatic build and unexpected misty conclusion of “Don’t Count Me Out.”

Throughout it all is Whitaker’s mastery of the Hammond B3 organ. He pays tribute to his organ inspirations here, but he developed his own strong voice. He solos with liberated fluidity, drawing on the blues, but avoiding clichés.

I have to single out “Expect Your Miracle,” with members of the New Hope Baptist Church stomping and clapping along in celebration. Whitaker doubles on organ and piano, a combination you don’t hear often. The pairing brightens and lightens the music. Thank the Lord Almighty for a record with real people clapping with real hands!

At once traditional and progressive, commercial and inspirational, this delightful listen is easily and strongly recommended.

— Allen Michie

Books

In With the In Crowd, (University Press of Mississippi) named after Ramsey Lewis’ 1965 hit, has two major threads. One details the lives of performers whose music was popular in the Black community in the ’60’s and the infrastructure — radio and record labels — that brought that music to listeners. The second thread lays out the case that jazz which was popular in the Black community during the ’60s has been overlooked by jazz historians. Author Mike Smith argues that more serious attention should be paid to performers like singer Nancy Wilson and Ramsey Lewis. Instead, the focus has been on the evolution of the avant-garde — Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane and a few others.

Smith believes that reason for the neglect is the need to “elevate” jazz from a popular musical form to one “equal” to European and other Western music. Early attacks on jazz, he argues, “led to a defensiveness and a need to seek legitimacy…”

Smith finds the absence of Nancy Wilson from jazz history the most irritating. He points out that she sold millions of records and received many honors. He says that, because the media loves conflict, writers’ attention has been drawn to the dramas that surrounded musicians like Billie Holiday and Nina Simone. He believes that the music made by Wilson and others reflects a more non-conflictual perspective on Black life, which was not just about struggle and trauma — there was beauty as well.

Smith has much to say about the organists of the era — Jack McDuff, Jimmy Smith, and others. And that pays off: he supplies a fascinating history of the Hammond organ. Inventor Lorens Hammond developed patents for 3-D movies and the first electric clock and he used that technology to create a compact organ. In the ’30s, he sold his organs as replacements for pipe organs in Black churches.

Smith observes that, unlike the compositions of the avant-garde, much of this music was danceable, pointing to the grooves in “Watermelon Man” and “Sidewinder.” He also details how important DJ’s were to the propagation of the music. Local authorities understood their status in the community; they turned to DJ’s to try and quell violence in the wake of the killing of MLK. Smith insists that, in 1960, the most trusted man in white America might have been Walter Cronkite. But in Black America “that title would probably have gone to a deejay. Probably Daddy-O-Daylie.”

Great music was created in that era and Smith makes a compelling case about how the music was made, distributed, and thought about. Whether or not the music has received due appreciation — that remains an open question.

— Steve Provizer

Part of the argument of Andrew Krinks’ White Property, Black Trespass: Racial Capitalism and the Religious Function of Mass Criminalization (New York University Press, 312 pages) is that the 18th century saw the beginning of “modern police and prisons” and since then policing and incarceration have served not only as a “means of establishing and defending the hierarchies of racial capitalist order by controlling Black, Indigenous, and other dispossessed people,” but also as vehicles “best understood…as a religious phenomenon.”

Part of the argument of Andrew Krinks’ White Property, Black Trespass: Racial Capitalism and the Religious Function of Mass Criminalization (New York University Press, 312 pages) is that the 18th century saw the beginning of “modern police and prisons” and since then policing and incarceration have served not only as a “means of establishing and defending the hierarchies of racial capitalist order by controlling Black, Indigenous, and other dispossessed people,” but also as vehicles “best understood…as a religious phenomenon.”

An independent scholar, educator, and movement builder based in Nashville, Tennessee, Krinks goes well beyond undercutting how various Europeans — well intentioned or not — defended their conduct as necessary to “save” the Indigenous people they enslaved or slaughtered. His all-or-nothing contention is that “whiteness is best understood as a manifestation of the aspiration to godlike transcendence and power, a means of exercising near total control over people and planet.”

Assume that that sense of absolute entitlement continues to this day, and it follows that undoing the oppressive work of police and prisons will require more than the rise of transformative justice, but the practice of what Krinks calls “the religion of abolition.” In keep with this sentiment, he closes his ambitious and challenging book with “May it be so. Amen.”

— Bill Littlefield

Strapped for cash, the young scholarship student dropped out of New York’s Art Students League. He took a union job with an outdoor advertising company that operated across the city’s five boroughs. Working from small photos and layouts, he and his crew hand painted marquees, backdrops, and gigantic advertising signs high above the city, often repainting the same walls and billboards over and over. At age 25, he was head painter for another firm. That year, two of his friends fell from the scaffolding while working and died. He quit his job, took a downtown studio, and became one of the leading figures of the 1960s Pop Art movement.

Strapped for cash, the young scholarship student dropped out of New York’s Art Students League. He took a union job with an outdoor advertising company that operated across the city’s five boroughs. Working from small photos and layouts, he and his crew hand painted marquees, backdrops, and gigantic advertising signs high above the city, often repainting the same walls and billboards over and over. At age 25, he was head painter for another firm. That year, two of his friends fell from the scaffolding while working and died. He quit his job, took a downtown studio, and became one of the leading figures of the 1960s Pop Art movement.

This famous tale opens the short essay that begins James Rosenquist: Collages, Drawings, and Paintings in Process (Princeton/No More Rulers, 2024). Sarah C. Bancroft, head curator of Rosenquist’s estate, recounts how the artist adapted the techniques he had learned in a now-vanished form of commercial art into monumental and mysterious paintings that blended the cropped, scaled-up, decontextualized imagery he found in sources like Life Magazine, juxtaposed to create enigmas as unsettling as the surrealist collages from a generation before.

The rest of the volume is a picture book reproducing preparatory studies for some major Rosenquist paintings. They show how the artist fragmented and repurposed printed advertisements into near-abstractions that boiled down the visual obsessions of mid-century America into work that is both commentary and homage. Beautifully printed, the clippings, sketches, and color studies stand up to the finished work in aesthetic quality. Larry Warsh, editor of the No More Rulers series (disclosure: I wrote for his publications for more than a decade) writes: “It’s our hope that the series… inspire visual thinking… and the inner artist in us all.”

— Peter Walsh

Damir Karakaš’ ironically titled novella Celebration (Two Lines Press, translated from the Croatian by Ellen Elias-Bursać, 116 pages) probes the making of a fascist, but the protagonist’s commitment is not driven by his acceptance of a racist ideology. His choice appears to be propelled, almost innocently, by a prosaic current of amoral brutality, the Darwinian struggle for survival among the underclass. The opening section (“House’) has Mijo nervously hiding in the woods around his farm. In 1941, he had joined the Ustaše, a terrorist group that, in the name of fighting for Yugoslavian independence, engaged in a succession of terrorist activities, including the mass killing (in the hundreds of thousands) of Jews, Serbs, and Roma.

Damir Karakaš’ ironically titled novella Celebration (Two Lines Press, translated from the Croatian by Ellen Elias-Bursać, 116 pages) probes the making of a fascist, but the protagonist’s commitment is not driven by his acceptance of a racist ideology. His choice appears to be propelled, almost innocently, by a prosaic current of amoral brutality, the Darwinian struggle for survival among the underclass. The opening section (“House’) has Mijo nervously hiding in the woods around his farm. In 1941, he had joined the Ustaše, a terrorist group that, in the name of fighting for Yugoslavian independence, engaged in a succession of terrorist activities, including the mass killing (in the hundreds of thousands) of Jews, Serbs, and Roma.

The war is over and members of the Ustaše are being hunted. We learn nothing from Mijo regarding what he did with the Ustaše: is he repressing his experiences? Instead, along with treasuring memories of work and family, he concocts a puerile fantasy, hoping that “when he first set foot outside of his hiding place, a different world would be out there where enemies would no longer be enemies and he would no longer be somebody on the run: all would be as if he’d been born again …” The religious sentiment cuts against much of what follows. Karakaš leaves this episode unresolved, as well as the three others in the book. The narrative jumps back in time, detailing Mijo’s hardscrabble, at times agonizing, existence. He is surrounded by the beauty of nature, to which he is sensitive (Karakaš details that response with an artful delicacy smoothly conveyed in Ellen Elias-Bursać’s translation), but Mijo is beset by the afflictions underlined in Ingeborg Bachmann’s poem “No Delicacies”: “Hunger/Shame/Tears/and/ Darkness.”)

“Dogs” takes place in 1935. The authorities decree that, after an officer is attacked by a dog, all of the canines in the village must be done away with. Mijo is sent out to kill his puppy. Set in 1941, “Celebration” has Mijo, accompanied by his future wife and her brother, making the long trip by foot to town to take part in an observance of Croatia’s independence. The most harrowing episode, 1928’s “Father,” is the last. The family is starving; there are too many mouths to feed. Mijo’s father takes his ailing father out to the forest to die. Disobeying his father’s command that he stay away, Mijo trails him on his pitiless mission. At one point, the father thinks “how in this world the only abundance was of evil and trouble, and with these words he was overcome with bleak and vague forebodings.” The Ustaša (“Insurgence”) movement would form a year later.

— Bill Marx

Maybe it is because Swiss writer Max Frisch’s Biedermann und die Brandstifter is being staged in Boston this month, but Swiss playwright/visual artist Ariane Koch’s zany first novel, Overstaying (Dorothy, A Publishing Project, adroitly translated from the German by Damion Searls) struck me as an wonderfully entertaining update. This is an exercise in tragic-comic absurdism squared.

Maybe it is because Swiss writer Max Frisch’s Biedermann und die Brandstifter is being staged in Boston this month, but Swiss playwright/visual artist Ariane Koch’s zany first novel, Overstaying (Dorothy, A Publishing Project, adroitly translated from the German by Damion Searls) struck me as an wonderfully entertaining update. This is an exercise in tragic-comic absurdism squared.

Smooth-talking firebugs moved into an incurious bourgeois home in Frisch’s play. Koch’s volume, which in 2021 won the Aspeckte Prize for debut German fiction, introduces a shape-shifting visitor into the ten-room home of a nameless young female protagonist who despises her small town but is too afraid — or vituperative — to leave. The woman may be a hunchback (?) whose egomania — driven by her condescension to all around her — resonates with the misanthropic wordsmithing of Thomas Bernhard. But few of the latter’s talkers skitter so quickly between optimism and pessimism, hop so unpredictably between self-congratulation and despair.

And Koch’s narrator projects a goofily surrealistic world that’s far from Bernhard’s glum atmospherics. Woven out of linguistic overkill, this askew context ends up making a kind of imaginative sense. Who is the visitor? Well, he assumes countless roles: servant, pet, lover, vampire, opportunist, muscleman, etc. Does he control her? Or she him? At one point she worries that he is “chafing me raw with his solicitude”: “He takes delight in woodworms, in tractors driving by, in balloons going up. Just like that the visitor has become a blithe spirit, happy to spend hours doing the most boring things … the visitor’s new optimism vis-à-vis life is like a screeching power saw in my ears. His intact moral state is like a thorn in my eye. The visitor is exemplary but I don’t need any exemplars. I need a cleaning man or lady for my house and home, especially my house, since I don’t exactly have a home.” The woman says that her favorite animal is the chameleon, and that beast is Koch’s daffy muse for this satiric study in domestic domination and submission.

— Bill Marx

Electronic Music

When Seefeel emerged in the early ‘90s, the barriers that had been set between rock and electronic music were much stronger than they are today. Associated with the shoegaze scene, the group quickly developed a form of ambient music that drew on guitars (processed through samplers.) In 1994 Seefeel signed up with the legendary dance music imprint Warp. They’ve broken up and gotten back together several times, but the 2021 box set Rupt & Flex may have revived their interest in making new music.

When Seefeel emerged in the early ‘90s, the barriers that had been set between rock and electronic music were much stronger than they are today. Associated with the shoegaze scene, the group quickly developed a form of ambient music that drew on guitars (processed through samplers.) In 1994 Seefeel signed up with the legendary dance music imprint Warp. They’ve broken up and gotten back together several times, but the 2021 box set Rupt & Flex may have revived their interest in making new music.

Now down to the duo of Mark Clifford and Sarah Peacock, Seefeel’s new 6-song ep Everything Squared (Warp Records) continue their penchant for deforming recognizable sounds. “Sky Hooks” is startlingly minimal, with Peacock’s voice pitched up and edited into a birdlike chirp. The song becomes complex, but it begins with barely more than percussion and faint keyboards. Throughout, the band composes via this strategy, starting off with a skeletal track and adding further loops to it. “Lose the Minus,” the only song with audible guitar, begins with a brief series of notes that echo into the distance. “Antiskeptic” soaks its drums in cavernous reverb, turning them into monstrous footsteps.

The mood of Everything Squared is forlorn. The music’s prettiness can’t conceal its underlying depression and loneliness. Part of darkness comes from Peacock’s voice. She hints at direct expression, but the production chops up her vocals. She is left just on the verge of singing actual words. Songwriting formulas function because certain common chord progressions and patterns of notes tend to be psychologically satisfying. Seefeel avoid them. Rather than writing melodies, Seefeel juxtapose and repeat textures without an interest in resolving them into satisfying patterns.

Ambient music has become background music to ease workers through their day Everything Squared delivers a dissident, bleak version. The impact of this album won’t fade away easily; the emotions it generates are impossible to ignore. Seefeel know how to make machines ache.

— Steve Erickson

Tagged: "Everything Squared", "In With the In Crowd", "Keel Road", "On Their Shoulders: An Organ Tribute", "Overstaying", "Rooted", "White Property Black Trespass", " A Dill Pickle", Ariane Koch, Damir Karakaš’, James Rosenquist: Collages Drawings and Paintings in Process", Joana Mallwitz, Konzerthausorchester Berlin, Matt Malsky, Matthew Whitaker, Mike Smith, Neave Trio, Seefeel, celebration