Jazz Commentary: String Quartet Omnibus, 2024

By Steve Elman

Three recent projects offer some fascinating examples of the futility of genre pigeonholes and some muscular engagements by “jazz” composers with the string quartet. But who will play these works in the future? Who will listen? And most importantly for the artists, who will buy?

Ryan Truesdell’s Synthesis Project; Wadada Leo Smith: String Quartet No. 17, world premiere performance by FLUX Quartet (April 20, 2024); FLUX Quartet & Oliver Lake: Right up On

(Editor’s note: The magazine customarily puts the names of CDs in italics and puts tune titles in quotation marks. But each of the 25 pieces under review could be programmed as a concert work, so we would ordinarily put them in italics. The decision has been made to put names of the two CDs, as well as all the works played, in italics. The titles of movements within works will be in quotation marks.)

What is the artist’s responsibility in a Time of Troubles? Many artists hunker down and do what they see as their job – to create Beauty, even if it is Ugly Beauty (in Thelonious Monk’s words). Some, despite the times, are compelled to scratch aesthetic itches that cannot be denied. Some seek to provide answers to the problems of the times – but there be monsters in those waters. The wisest artists use their work to pose questions rather than answers, in the hope of provoking the thoughts of their audiences.

Two recent CD releases and one live performance in our area give us the greatest opportunity ever to see how artists known primarily as jazz musicians engage with the inexhaustibly interesting medium of the string quartet – and how 17 of them work in our Time of Troubles.

But who will listen? And more importantly for the artists, who will buy?

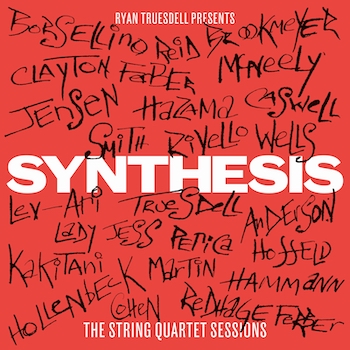

Ryan Truesdell is known primarily for his championing of the music of Gil Evans. His new project, Synthesis (artistshare, 2024), is the result of his interest in the string quartet. It includes three pieces of his own (two with additional instruments added to the quartet) and 14 pieces from other composers primarily known as jazz musicians. It is a rich kaleidoscope.

This engaging horizontal survey stands next to the greatest vertical adventure into the medium of the string quartet yet attempted by someone thought of as a jazz musician, the (so far) 17 string quartets of Wadada Leo Smith. The latest of those 17, The Capital, Washington, DC: An American Experiment in Democracy and Capitalism, had its world premiere in Cambridge on April 20.

In that performance, Smith’s quartet was played brilliantly by FLUX, a quartet led by Tom Chiu. That event offers me a chance to look back a bit and also discuss string quartet works by Oliver Lake played by FLUX in a 2016 release.

Because of the variety of works in Synthesis, it seems logical to begin there, and then look to Smith and Lake for their personal approaches to the medium.

Most of the pieces in Synthesis are contemporary responses to Truesdell’s call for short works, and in some ways, Synthesis presents an illuminating survey, across three CDs, of the ways in which composers deal with the idea of audience appeal.

The exceptions are Bob Brookmeyer’s Talking, a posthumous recording of a previously unrecorded work, and Rufus Reid’s String Quartet No. 1, which seems to be a work waiting for the kind of opportunity Truesdell offered. These two works (along with John Clayton’s Tidal Wave and Oded Lev-Ari’s Playground) strike this listener as the purest exercises in form in the collection. Their composers do not seem to be concerned with creating music that will have a particular impact or produce a particular reaction in their audiences.

On the other end of the spectrum are works whose composers seem genuinely interested in creating music with direct appeal. Jazz listeners should respond well to Christine Jensen’s Tilting World, a showcase for violinist Sara Caswell, who has an improvised solo in the middle over a bass line from the cello and something like comping from the other two voices. Another piece that should readily speak to jazzpeople is Alan Ferber’s Violet Soul, another feature for Caswell with similar support from the other three voices.

Australian composer Vanessa Perica, whose A World Lies Waiting in Synthesis will appeal to classical listeners as much as to jazz listeners. Photo: Pia Johnson

Classical listeners will find much to enjoy in Vanessa Perica’s A World Lies Waiting, which shows Perica’s ease and grace in writing for this idiom. These 7½ minutes could reside comfortably in the repertoire of any of the major quartets working today. And Truesdell’s own Suite for Clarinet and String Quartet is a worthy successor to landmark works for the same instrumentation by Mozart and Brahms. Like those pieces, it is a showcase for the abilities of a particular virtuoso – in this case, the dazzling Anat Cohen, who rises to every challenge and makes the Suite one of the highlights of Synthesis.

Those who favor the trappings of pop will likely respond to the only work here for quartet and tape, Paper Cranes by Berklee faculty member Joseph Borsellino III, a saxophonist and pianist who also holds a degree in composition from the New England Conservatory. This is an immediately appealing, radio-friendly piece with a lot packed into 6:43. The tape elements, prepared by Borsellino, simulate minimalist keyboard figures at first and later settle into the role of drum kit under the quartet’s development of a motif that resembles a lick from Paul McCartney’s “Listen to What the Man Said.”

In between these extremes are works with a variety of goals, all well-achieved.

Asuka Kakitani’s Melt is carefully-wrought, a bit bluesy, and seems to do just what its title suggests – it follows the progress of a solid into a liquid, and then drips away into silence.

Miho Hazama, who leads her own little big band and writes impressively for it, contributed a work with a misleading title. One might think that Chipmunk Timmy’s Funny Sunny Day would be a light, whimsical piece, but this one is serious, mirroring the activity of a chipmunk from waking to sleeping (We may find chipmunks’ antics amusing, but for them, life is serious business, and Hazama seems to be taking Chipmunk Timmy’s point of view.)

Jim McNeely’s Murmuration and Adagio is an attractive piece, showing the sensibility of a jazz player, with lyrical thematic material in the most interesting section, built like a jazz soloist’s interpretation of a ballad.

Dave Rivello’s Two Reflections for String Quartet, with movements titled “Sorry” and “Not Sorry,” is effective, with unison chords at beginning and end bookending to a progression from a mournful mood to an energetic one. It is not dark to light or sad to happy, but something more sophisticated, emphasized by the fact that the quartet plays the two movements attacca (that is, without a pause).

Ryan Truesdell, composer and impresario of Synthesis. Photo: Marc Santos

Truesdell himself offers two pieces in addition to his clarinet quintet, and each of them is well worth hearing. His Dança de Quarto has a distinctly Brazilian feel and some of the most elegant counterpoint in the entire set. His Heart of Gold features cellist Jody Redhage Ferber and bassist Jay Anderson, who adds warm richness to the bottom of the ensemble; Ferber contributors a soulful melody statement here built on a theme that is reminiscent of “If I Fall in Love,” and Anderson’s wonderful sense of pulse infuses the piece with a delicately jazzy feel.

I looked forward to hearing John Hollenbeck’s Grey Cottage, but I was a bit disappointed. Hollenbeck is one of the most important current jazz composers, leading his own large ensemble and writing excellent music for it. But Grey Cottage is slight. It consists of seven mood pieces for the string quartet, exploring different approaches and effects, with marimba, trap set, and piano (all played by the composer) added for color. Each has a distinct character and particular message, but the whole is nothing more than the sum of its parts.

Sara Caswell, first violin on most of the Synthesis works and featured artist on three of them. Photo: Emma Mead

Finally, there is Nathan Parker Smith’s Where Can You Be? I was puzzled by Truesdell’s decision to use this work as the leadoff to the entire set. It has a fast – slow – fast structure with a strong middle-eastern feel, but little in the way of direct appeal to an audience; many of the other pieces have more immediate impact.

Hearing all three CDs of Synthesis gave me a great deal of pleasure and intellectual satisfaction, but I am not the average listener; I love the string quartet as a medium, live with jazz as my home music, and find classical music a rich source of aesthetic enjoyment across all its genres. I applaud Truesdell for his effort and the results, but I still wonder: who will listen? And who will buy?

Listeners (and buyers) were on hand at Harvard’s Paine Concert Hall in Cambridge on April 20 to hear Wadada Leo Smith’s latest string quartet. It was not a large crowd – perhaps 200 people – but they were attentive and enthusiastic, and they heard one of the world’s greatest new-music quartets play Smith’s piece with deep commitment and fire.

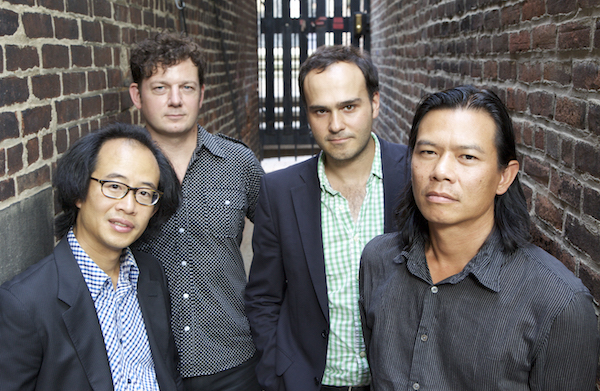

The performers were FLUX, a quartet led by first violinist Tom Chiu. Second violinist Conrad Harris is core to the group, but these two play regularly with sympathetic guests in the other chairs. For this evening, violist Carrie Frey and cellist Meghan Burke filled their roles admirably.

Smith’s music and his titles are not exactly independent of one another, but his titles do not offer a road map to his music. This was my first experience of hearing a Smith quartet in live performance, and it was deeply rewarding – not just for the music, which was great in substance, but for the fire and empathy of the quartet. Chiu was clearly the leader, and his visual cues to his partners were instructive to me in seeing the “bones” of the work.

Smith’s 17th quartet has the general title The Capital, Washington, DC: An American Experiment in Democracy and Capitalism. Each of the five movements also has a title, and the notes handed out at the concert, presumably reflecting Smith’s ideas, provided generous comments on his inspirations.

FLUX Quartet, showing the personnel that performed on Right up On. Left to right: first violinist and leader Tom Chiu; second violinist Conrad Harris; violist Max Mandel; cellist Felix Fan. Photo: courtesy of the artist

As an example, take the second movement, “The Lincoln Memorial.“ The notes said that it “looks at the monument where ‘activists and people of consciousness’ have gathered to resolve issues – Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s ‘I Have a Dream’ speech being one notable example.” But anyone looking for a declamatory statement like King’s speech or something like Aaron Copland’s inspirational music in “A Lincoln Portrait” would be nonplussed. The movement was marked by high notes from Chiu with almost constant comments from the other voices, followed by a long section of nearly-consonant music that dissolved into a passage of spontaneous performance (Smith is careful not to refer to this aspect of his writing as “free improvisation,” because he carefully defines the direction he wants his performers to take, often with graphic scores.)

On the other hand, the concert notes were pointed in describing the last movement, entitled “January Six: the Falcon Uplifted the Unity with Love.” The notes said that it “deals not with that now-infamous day’s uprising, but the spiritual unity that allowed the insurrection to be overcome.” And yet, this may have been the most directly programmatic movement, with a long spontaneous performance crescendo in the middle – possibly depicting the overcoming of the riot.

Wadada Leo Smith, unlike some of the composers represented in Synthesis, is not experimenting with the string quartet or venturing into the medium as a novice. He has refined (one might even say annealed) his language for the string quartet into a passionate voice with singular definition. As I noted above, he is not an artist who is trying to provide answers to the serious problems of our Time of Troubles. He is asking questions, and he invites his listeners to think deeply. Sometimes his questions are abstract, implied in his music. Sometimes they are specific, as in the case of the third movement of the 17th quartet, entitled ”The US Supreme Court, Can It Survive?”

Wadada Leo Smith, composer of 17 string quartets (so far). Photo: Michael Jackson.

When considering all the string quartet musics of the composers I heard for this post, that of saxophonist Oliver Lake is perhaps the least approachable for the average listener. There are no “pretty” themes. The quartet frequently works in an active interplay where it may be hard for a first-time listener to follow the voices. His own descriptions of his pieces do not offer clear guidelines for interpretation. But all of these caveats might be applied to the music Lake has been successfully making on his own as a saxophonist and flutist for almost 50 years.

Since his emergence as a major artist as one of the four masterful voices in the World Saxophone Quartet in the late 1970s, Lake has followed a personal path through many media, often in duets. Among his most interesting records are joint projects with trombonist Joseph Bowie (Live at A-Space [Toronto], Sackville, 1976), pianist Donal Fox (Boston Duets [recorded live at the Regattabar, Cambridge], Music & Arts, 1992), pianist Borah Bergman (A New Organization, Soul Note, 1999), and bassist William Parker (To Roy, Intakt, 2015).

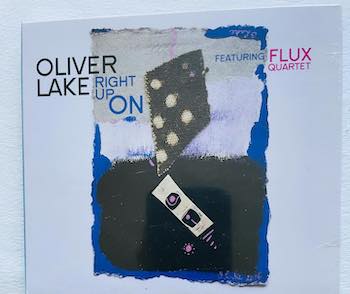

The cover art by Oliver Lake himself, showing off yet another example of this composer-saxophonist’s aesthetic.

His CD release Right up On (Passin’ Thru, 2017) puts the spotlight mostly on FLUX and Lake’s writing for string quartet, although the composer joins the group on alto saxophone for two of the seven works and has a very brief moment in one of the others.

FLUX shines throughout this release, as you might expect from their collaborations with Lake that have been going on since 2002. As in the 2024 performance, Tom Chiu and Conrad Harris are the first and second violins. Here Max Mandel is the violist and Felix Fan is the cellist, but the same sense of passion and intelligence that was on display in Paine Hall is here in abundance.

Perhaps the most immediately approachable of the works for quartet alone is the title composition, Right up On. Lake says it is “written with the concept of filling the space, each player right after the other,” and it unfolds as a single line of thought, working towards a conclusion of sorts. The harmonic language has the same pantonality as that of the other pieces, but there is something of a song-quality to some of the lines here, and it works logically towards a conclusive end, with a short tentative coda.

The major work on the CD is the 20+-minute Einstein 100! It was premiered in 2005, the 100th anniversary of the publication of Einstein’s theory of relativity, first put forward in a paper published in the German physics journal Annalen der Physik on June 30, 1905. Lake says it “contains solos for each member of the quartet, and provides the space for improvisation.” The “solos” are integrated fully into the piece, although there are brief moments in which each player has the spotlight to himself. It has a pulsing energy that works towards an acoustic fadeout, and the interest never flags despite its length.

Of the pieces in which Lake has a role, the most personal may be “5 Sisters,” dedicated to the memory of Lake’s mother and her four sisters. It is tempting to see the five voices here as representing the five women, but the music does not lend itself immediately to that interpretation; it is a constant flow of ideas back and forth, except for the end, where Lake’s saxophone disappears and the quartet has some spare figures to conclude – perhaps the four other sisters mourning Lake’s mother?

Oliver Lake n 2019. Photo: Charles Martin

There is no commonality of purpose among the 25 works I examined for this post – this is not surprising, since you would be hard pressed to find commonality among 25 classical works for quartet chosen at random. But these 25 share a common dilemma: who will perform them again?

Wadada Leo Smith has a great advantage in this regard over the other composers. As the only one who has been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, he has some cachet in the world of art, and he has been fortunate to cultivate relationships with academic institutions that have provided forums for his wide-ranging interests as composer and performer. He has built strong bonds with performers who understand his goals and methods, especially the RedKoral Quartet, which he helped to create, so his performances have passion as well as authenticity.

But even Smith’s music has not “crossed over” into the repertoire of major classical quartets; his music is like that of Heitor Villa-Lobos, another composer who wrote extensively for string quartet but whose works are rarely performed by today’s leading ensembles.

Ryan Truesdell has done a great service by putting his efforts into a showcase for “jazz composers” and we can hope that major quartets will take notice and embrace some of these works. Truesdell and the other composers provide detailed and interesting notes on the works in the liner notes, along with a listing of which string players are playing on which pieces. I heard all of these pieces without those notes, and I was pleased to see that, for the most part, my impressions lined up with the ideas of the composers, perhaps proving that the music really does speak for itself.

Oliver Lake surely will continue on his own creative path. The notes to Right up On indicate a longstanding interest in working with string quartets, and FLUX has an extensive history of collaboration with him. In addition, at least one other major quartet, the Arditti, has commissioned a work from him.

Here is music of depth, music to hear and to think about in a Time of Troubles. But who will play it again? Who will listen? And who will buy?

MORE:

Composers who are associated with jazz have been intrigued by the string quartet – it is so like a jazz ensemble and yet so unlike it at the same time. Ornette Coleman and John Lewis wrote pieces for it in the 1960s, but it is only within the past thirty years or so that the performance practices of classical string players have risen to a level that allows composers who are improvisers at heart to realize their visions fully.

Ryan Truesdell’s Synthesis is being made available as a “limited edition” CD set or as a download from artistshare. His Gil Evans Project orchestra has two CDs that masterfully revisit Evans classics and make the case for Evans pieces that had never been recorded previously (Centennial [ArtistShare, 2013] and Lines of Color [Blue Note / ArtistShare, 2016]).

I have already written about Wadada Leo Smith’s first 12 string quartets in a Fuse post. His quartets 13 – 17 have their inspirations in American issues past and present, and they all ask important questions in a Time of Troubles. He promises that a recording of these five will eventually come to pass, and it is likely that his work in the medium will continue as long as he does.

A live 2014 performance by Oliver Lake and FLUX (with the same members as those performing three years later on Right up On) at The Stone in New York City has been posted on YouTube. It shows the passion that Tom Chiu and his colleagues bring to their work, and there is more of Lake in these performances than there is on the CD. The works include pieces that were not part of those recorded for Right up On – Input, Stone 2, and Stone 1.

Another notable recent work that incorporates the traditional string quartet (in this case, the Harlem Quartet) is Jeff Scott’s Passion for Bach and Coltrane (Imani Winds Media, 2023). This is such a distinctive piece of music that it goes beyond the bounds of this post, and deserves a spotlight to itself; I discuss it in a stand-alone post to come.

Steve Elman’s more than four decades in New England public radio have included 10 years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host on WBUR in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, 13 years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB.