Book Review: “Ginster” — The Numbness, not the Glory, of War

By Thomas Filbin

The reissue of this novel now is valuable, beyond its considerable historical and aesthetic virtues, because it makes pertinent points about today’s world, bedeviled by war, misery, poverty, and the enticing lure of despotism as an answer to democracy’s shortcomings.

Ginster by Siefried Kracauer.Translated from the German by Carl Skoggard. Afterword by Johannes von Moltke. New York Review of Books Classics. 306pp. $18.95

Anti war novels, films, and art aren’t always strident, bulldozing attacks on man’s inhumanity to man. In fact, satire and black comedy can do a more effective job of communicating the insanity of mass murder for the sake of a cause. The admired Catch-22 (film and novel), nails the homicidal absurdity of war, while the great Paths of Glory (film and novel) takes a more grimly serious route. But here the craziness of warfare shines through the purported rationality of the story’s combattants. In Paths of Glory, when the French general explains that the pending execution of three hapless draftees as deserters will surely build morale among the rest of the regiment, the ironic revelation of the speaker’s inhumanity is plain. Visuals also take the same strategy. The World War One paintings of Otto Dix and Max Ernst say in paint what words often fail to convey about the inanity of war.

Anti war novels, films, and art aren’t always strident, bulldozing attacks on man’s inhumanity to man. In fact, satire and black comedy can do a more effective job of communicating the insanity of mass murder for the sake of a cause. The admired Catch-22 (film and novel), nails the homicidal absurdity of war, while the great Paths of Glory (film and novel) takes a more grimly serious route. But here the craziness of warfare shines through the purported rationality of the story’s combattants. In Paths of Glory, when the French general explains that the pending execution of three hapless draftees as deserters will surely build morale among the rest of the regiment, the ironic revelation of the speaker’s inhumanity is plain. Visuals also take the same strategy. The World War One paintings of Otto Dix and Max Ernst say in paint what words often fail to convey about the inanity of war.

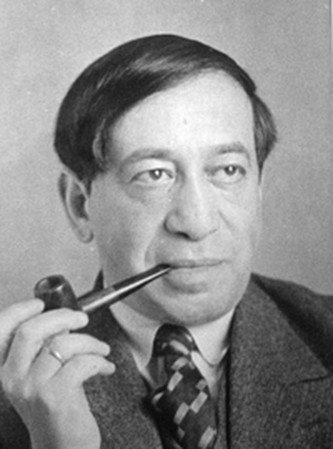

German writer, journalist, sociologist, cultural critic, and film theorist Siegfried Kracauer drew on an anti-capitalist perspective that has sometimes been associated with that of the Frankfurt School of critical theory. A brilliant but neglected analyst of modern art and society (at least in America), he adopts the insinuating satiric mode of antiwar advocacy in his fascinating 1928 novel Ginster. The book deals with the fallout of war, but not on the battlefield — it is in many ways a travelogue through a society that is in the midst of a nervous breakdown. Its dramatis personae do not respond to war’s horror with hysteria, but with a kind of numbness — this is a vision of death-in-life.

Protagonist Ginster is a nondescript nobody who is twenty-five years old when World War One breaks out. He has completed his architectural training and is initially deemed unfit for military service. Sporting an amorphous sensibility, he spends his time exploring the world, meeting new people and then unfailingly falling under their individual spells. In some ways, he is yet another variation on Voltaire’s Candide. He accepts the world as it is presented to him without question — until the scales eventually fall from his eyes.

In a flashback to Ginster’s school days, the reader is given a secret notebook that the character used to judge and grade his fellow students. He is both deeply insecure yet convinced, in a quiet way, of his own superiority. Ginster both envies and despises young men who are better adapted to succeeding at life: “He had often studied young fellows, hoping to figure out the tricks they used to mesmerize a girl.” He bluffs about experiences with women; he tells one girl he is friends with a Polish countess, but the woman is a creature of his cartoon fantasy. She has dyed red hair, travels the world, arranges a rendezvous with Ginster via a telegram.

As the war drags on, and increasing casualties deplete the ranks, Ginster is reclassified as suitable for war use, at least in an emergency. But by now he has seen through the false consciousness generated by authorities to sustain the war effort. He is cynical: “Hating the emotions, the patriotism, the huzzahs, the banners; they obstructed one’s view and people were dying for nothing.” He hears of front-line battles and “…wondered how it was that officers whose profession demanded courage dove into cellars as soon as the alarm signal was received.” He is assigned to be part of an artillery unit because this duty would be less arduous than marching continually as an infantryman. But when an architectural competition is announced for the construction of a military cemetery he enters and is part of the winning team. How to deal with heroes who come home dead? The government figures that society would be mollified and the corpses “feel better in beautiful graves at home.” Kracauer’s savage sarcasm comes out into the open here, deflating illusions of the splendor of memorializing the war.

Siegfried Kracauer Photo: Diaphanes

Winning the competition gives Ginster work, but building a cemetery dedicated to the dead raises its own peculiar problems. Some bodies are not recoverable — memorials or cenotaphs must suffice. A more serious issue: how large should the cemetery be? The fighting is raging on with no end in sight. Plans to make the cemetery infinitely large are, in ways, treasonous because it implies casualties will only continue to mount up.

Eventually, Ginster condemns human existence because it is essentially about the absorption of the individual into the mass, an organized effort at eradicating difference.

Despite his twenty-eight years, Ginster detested the necessity of becoming a man. All the men he knew had set views and professions…they were like heavy body masses confidently asserting themselves and refusing to share. Unlike them he would have liked to exist as a gas; at least he could not imagine ever solidifying into anything so impenetrable.

After the war ends, and the German government falls, Ginster has hopes for a better world. But he hasn’t the imagination necessary to project the future. He meets a woman and she asks him about his childhood. His answer: “I don’t know a thing. I don’t remember.” The old world is gone forever, but, without a sense of the trauma of what he and what society went through, Ginster is lost in time.

University of Michigan academic Johannes von Moltke’s illuminating afterword contextualizes Ginster as a ‘modernist’ antiwar novel. “Who, then, is Ginster?,” he writes. “The question occupied the earliest readers of Siegfried Kracauer’s novel but their perplexity might as well be ours…” He goes on to speculate that “Ginster becomes a medium for the fever dream that is Germany in the first decades of the 20th century…”. That “fever dream” is relevant today for obvious reasons. Kracauer grasped the disillusionment and nihilism generated by the First World War and its aftermath (Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms was published in 1929). The reissue of this novel now is valuable, beyond its considerable historical and aesthetic virtues, because it makes pertinent points about today’s world, bedeviled by war, misery, poverty, and the enticing lure of despotism as an answer to democracy’s shortcomings.

Thomas Filbin is a freelance book critic whose work has appeared in The New York Times Book Review, The Boston Sunday Globe, and The Hudson Review. His novel The Black Amphora of Halicarnassus has recently been published.

In film circles, Kracauer has not been neglected in America with his From Caligari to Hitler a major text for seeing how the desire for Nazism was reflected in German cinema of the 1920s.