Visual Arts Review: Firelei Báez at the ICA — No Question, A Star Is Born

By Trevor Fairbrother

The artist is currently facing the existential throes of art-world fame and fortune.

Firelei Báez with Untitled (Temple of Time), 2020, plus detail of left edge of the painting. Photo: courtesy of the ICA

Firelei Báez was born in 1981 in the Caribbean city of Santiago de los Caballeros. Her parents exemplified the sovereignties and the main ethnic groups that have divided the island of Hispaniola since the mid-19th century: her mother Dominican, her father of Haitian descent. Aged 10, accompanied by her mother and sisters, she moved to Miami. Pursuit of an art school education led her to New York City (BFA from Cooper Union in 2004 and MFA from Hunter College in 2011), which remains her base.

A detail from Firelei Báez’s Can I Pass? Introducing the Paper Bag to the Fan Test for the Month of June, 2011. Photo: courtesy of the ICA

Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art has organized the first North American museum survey of the artist’s work (on view through September 2). Visitors will find paintings, works on paper, and installations abundant in vivid colors, patterns, and textures. Báez focuses on women of color, envisioned in situations ranging from energized abstract fields to montaged maps, architectural diagrams, written texts, and emblems of Black empowerment. Spectacle and confrontation work hand in glove to generate magical, symbolist, surreal, and sociopolitical reverberations. She says her emphasis on the body “serves as a tool for navigation in questioning and re-imagining normative histories.” The introductory wall text in the ICA’s exhibition quotes her thus: “My works are propositions, meant to create alternate pasts and potential futures, questioning history and culture in order to provide a space for reassessing the present.”

An early work indicates that Báez’s evolution as a questioner involved exercises to calibrate her singularity in the spectrum of Afro-Caribbean identity. It is a suite of 31 self-portraits painted on matching panels that are hung in a tight gridded arrangement. Each head is an area of hastily applied light brown paint set against a solid white ground. The artist details just two attributes — her hair reduced to an intricate linear outline and her eyes rendered with realistic precision. She made these portraits on a daily basis in the course of one month in 2011. Each day she mixed a paint sample to match the color of her forearm. The title Báez crafted — Can I Pass? Introducing the Paper Bag to the Fan Test for the Month of June — flags bogus practices used to categorize people as Black or white. In the early 20th century one gauge in the US was to see if the skin was lighter or darker than a generic brown paper bag. (In 2015 the artist noted that the supremacy of Beyoncé and President Obama depended in part on meeting that criterion.) In Báez’s homeland, nightclubs and other gathering places used electric fans to enforce restrictions: those Dominican citizens whose hair moved freely in the breeze were deemed white. In most of the panels of Can I Pass? the eyes look defiantly at the viewer. The artist has observed, “I retained the gaze out of a need for personal agency, to act as a counterbalance to the inherent psychic violence in those two tests.”

Firelei Báez, Sans-Souci (This threshold between a dematerialized and a historicized body) with detail, 2015. Photo: courtesy of the ICA

Báez brings the vocabulary of Western European portraiture into play as she interrogates racialized histories. In 2015 she imagined a historic woman of color in a painting on linen that is nine feet tall: Sans-Souci (This threshold between a dematerialized and a historicized body). The first words of the title are French for “no worries” or “carefree.” They also resonate in Caribbean history. Sans-Souci was the majestic royal palace built in Haiti by Henri Christophe, a former slave who became a general in the revolutionary war against the French colonizers; Christophe crowned himself king in 1804. And Jean-Baptiste Sans Souci was another Black military leader who fought the French in the same war. The headdress in the portrait recalls the tignons or knotted scarves that all women of color in New Orleans were legally bound to wear when the city was under Spanish rule. While the “tignon law” was intended to discourage interracial marriage by visibly identifying women who were not white, it inadvertently inspired all women of color to subvert hierarchy by fashioning sumptuous and elaborate headwear. Close inspection of the fabrics in Sans-Souci reveals such motifs as raised fists, broken chains, and attacking panthers, used by activists in different countries and eras. The woman’s skin combines different colors that flow and mix. Pouring paint is a favorite studio practice of Báez, who uses it for experimentation and “happy accidents” that spur her to visualize compositional possibilities.

A detail from Firelei Báez’s Man Without a Country (aka anthropophagist wading in the Artibonite River), 2014–15. Photo: courtesy of the ICA

Brooklyn’s annual West Indian Parade gives Báez, a self-described “Caribbean hybrid,” the opportunity to put her own resilience into context. The ICA’s show includes two large full-length portraits of dancers at the carnival: Anayansi (2010) and Cybil (2011). The artist construed the costumes, especially the feather headdresses, as attempts to “perform” constructed Native American identities, adding, “This act seemed like a safeguard against the painful histories of colonialism and slavery.” Thus, she improvised embellishments that are ambiguous: on the one hand they recall 16th-century European depictions of indigenous peoples in the Americas, yet are equally compelling as homages to latter-day participants in the West Indian Parade.

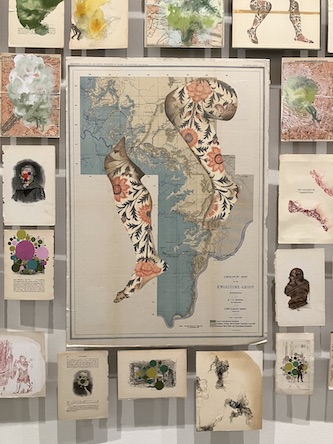

This line of enquiry led to the remarkable 2014–15 multimedia work Man Without a Country (aka anthropophagist wading in the Artibonite River). It features 225 individual pages culled from books of various sizes and ages that had been deaccessioned from institutional libraries in New York. Báez added imaginary figures and colorful abstract patterns to the sheets and gave each a backing support that allows wall-mounting. When installed, the asymmetric ensemble, over 20 feet wide, hovers in front of the wall like a school of fish. The opposite of an absolutist map or diagram, it is a gathering of oblique strategies to be consulted ad hoc. As a student, Báez was surprised to learn that Cooper Union periodically removed old, unused outmoded publications from its holdings: “It was almost a divesting of ethics and ideas, the old guard, or things that were not in sync with the present.” She decided to alter and reanimate these colorless academic castoffs with fanciful decorations and folkloric imagery and invite viewers to journey freely through her cosmos-like creation. The title of this work alludes to Haitian geography and colonialist allegations of cannibalism. The artist has said that in the Dominican Republic the natural and civil rights of people of Haitian descent are often disregarded.

The largest work on view at the ICA — A Drexcyen chronocommons (To win the war you fought it sideways) — is a 2019 mixed media installation that invokes a bower or sanctuary on the ocean floor. Visitors enter a place where starry light arrives through the hand-perforated blue tarps covering the ceiling and walls. The illusion of a nurturing grotto is boosted by bold tropical foliage and printed blue-and-white fabric patterned with symbols of Black self-determination. Two large paintings of seated nude women with indigo tignons are focal points. The grace and iridescence of the figures may trigger diverse associations: Aretha Franklin’s joyful Afrocentric phase? Mughal court portraiture? psychedelic sirens? or esoteric priestesses? A comment by Báez quoted in the ICA’s label text confirms that this is a site of veneration: “To psychologically inhabit a femme space is a transformative gesture. It is a radical positioning that could truly enable a different way of organizing space and bodies and nature and spirits — an otherwise world order.”

Firelei Báez, A Drexcyen chronocommons (To win the war you fought it sideways), 2019. Photo: courtesy of the ICA

Báez has a penchant for elliptical and discursive titles. She thinks of them as independent works that further the speculative and poetic reach of her art. A Drexcyen chronocommons (To win the war you fought it sideways) is a case in point. The ICA’s wall label rightly focuses on the first part — a reference to an electronic music duo from Detroit whose debut vinyl release was Deep Sea Dweller. From 1992 through 2002 a myth germinated in Drexciya’s techno recordings and narrative fantasizing. They imagined an aquatic Black community descended from the unborn children of pregnant women thrown overboard from transatlantic slave ships. I had to search the internet for the phrase Báez inserted parenthetically in her title. It comes from Major Gentl and the Achimota Wars, a 1992 anticolonialist Afrofuturist novel by Kojo B. Laing (“[They met] in the middle of their minds, with all inessentials gone: to win the war you fought it sideways.”).

The ICA is showing nine splendid and ambitious paintings from 2019-22 in which Báez supersizes her successful tactic of adding pictorial additions on top of printed matter. First, she uses inkjet printing on canvas to make a monumental enlargement of a historical map, chart, or engineering diagram. Then she makes painterly improvisations on that substrate. The finished works are magnificent, running the gamut from abstraction to still life and figuration. One with a palette of greenish yellow, puce, and pale blue may well be completely abstract. Another looks like a magnification of marbleized paper in orange, blue, and lavender; but scrutiny will reveal a maelstrom of celestial horses, large and small.

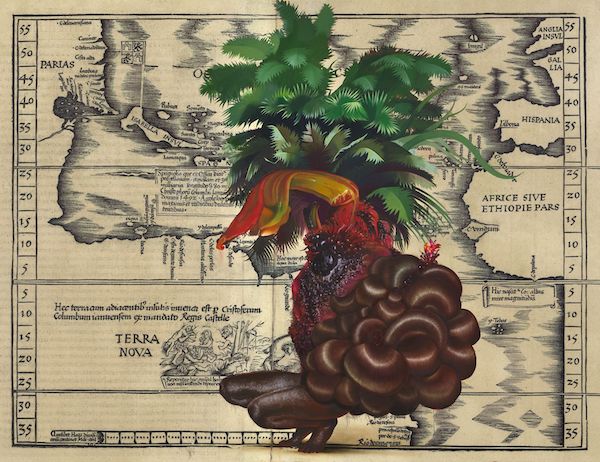

Firelei Báez, Untitled (Terra Nova), 2020. Photo: courtesy of the ICA

The painted image in Untitled (Terra Nova) evokes a wild female creature from Dominican folklore: the wily and elusive Ciguapa. She is a lethal wood-dweller who elicits wonder and caution about the power and unruliness of nature. Báez depicts a crouching Ciguapa, armored with buns of straightened black hair and camouflaged with succulent plant matter. She lies in wait, ready to resist all that is symbolized in a map of the Atlantic Ocean engraved by Laurent Fries, published in France in 1535 and 1541. Two telling details in the left half of the map reveal the mindset of colonizing Europeans: the vignette next to the words “Terra Nova” (South America) depicts indigenous people engaged in cannibalism, and a Spanish flag has been raised over the island “Isabella Insul.” (Cuba).

Multicolored vector lines converging in a golden yellow center make Untitled (Temple of Time) uncommonly riveting. The effect is technically nonobjective, but viewed in relation to the printed composition that underlies it, one can imagine the portrait of a supernova — sparkling light that is the remnant of an exploding star in this or a more distant galaxy. The inkjet substrate of this work presents an equally eye-popping chart published in New York in 1846 by the educator and feminist reformer Emma Willard. The author of history and geography textbooks, Willard believed her students remembered information that was delivered in a graphic format. In Willard’s Map of Time (aka The Temple of Time) the educator juxtaposed numerous timelines in the form of an Ionic temple viewed in one-point perspective. The present occupies the foreground and the edifice tunnels back to 4004 BCE, with a column for each century. The columns nearest the viewer are incomplete because Willard’s creation originated in the middle of that century. She divided the ceiling into five bands presenting lineages of important figures in different fields, including “Theologians” and “Warriors.” The most recent space in the category of “Poets, Painters &c.” names four male writers: Scott, Byron, Coleridge, Goethe. In overpainting Willard’s map with her rainbow supernova, Báez foresees an era when history is not exclusively “Western Civilization” set in stone, when efforts to understand the present and the past reach for a continuum that feels liberated and open-ended and “abstract.”

Eva Respini curated this exhibition and edited the handsome catalogue. The publication has eight essays written by women: a professor of American Studies and Ethnic Studies and seven museum professionals. One intriguing component is the contribution by Firelei Báez: a 40-page “Sketchbook” in which she illustrates a diverse array of works on paper alongside handwritten annotations. The artist writes informally about her thinking as a maker. The catalogue deftly balances essays in a “scholarly” format, plentiful color reproductions of Báez ‘s finished works, and the disarming informality of her “Sketchbook” contribution.

The cover of the ICA’s catalogue. A detail from the painting Untitled (Les tables de géographie réduites en un jeu de cartes), 2022.

The artist is currently facing the existential throes of art-world fame and fortune. In September 2023 ArtNews reported that Báez “has joined Hauser & Wirth, the global market juggernaut with more than a dozen galleries.” In October 2034 Denmark’s Louisiana Museum of Modern Art opened a large exhibition of recent work, her first solo exhibition in Europe; it is titled Trust Memory over History. In March 2024 the president of the mega-gallery told ArtNews that he sold a new painting by Báez at the Freize art fair in Los Angeles for $415,000. A month later the ICA unveiled its project, and the credits for the exhibition included this statement: “Major support for Firelei Báez is provided by Hauser & Wirth, the Henry Luce Foundation, and The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.” (I’m not dissing the ICA for taking money from a commercial gallery; it happens nowadays. The presentation of a Raqib Shaw exhibition currently at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum is funded in part by White Cube and by Pace Gallery.) The promotional blurb for the ICA’s accompanying catalogue says, “This exhibition will offer audiences a timely opportunity to gain a holistic understanding of Báez’s complex and profoundly moving body of work, cementing her as one of the most important artists of the early 21st century.” No question, cemented or otherwise, a star is born. Thankfully, for Bostonians, the ICA has finessed a very rewarding project and it already has a major work in its permanent collection (Man Without a Country …, 2014-15).

Trevor Fairbrother is a curator and writer. In the last century he worked on a few projects for the ICA: in 1988, for example, he was co-curator (with Elisabeth Sussman and David Joselit) of the exhibition American Art of the Late ’80s and contributed to the accompanying catalogue.

Trevor Fairbrother © 2024