Music Commentary: A Mystery Solved on the 50th Anniversary of the Release of “Queen II”

By Adam Ellsworth

It is well established that the lyrics to the song on Queen II that’s directly about the painting (called “The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke”) originate from a poem Richard Dadd wrote about his picture. What’s never been established though is exactly how Freddie Mercury became aware of this poem, or how he would have had the opportunity to read any of its lines (he couldn’t just Google it after all).

Before Queen entered the studio to record their second album, frontman Freddie Mercury organized a field trip.

Before Queen entered the studio to record their second album, frontman Freddie Mercury organized a field trip.

The group’s self-titled debut had only just been released, but thanks to the lengthy delay between when the record was cut and when it hit the shops, Mercury and his bandmates had already moved past it. They were ready for something more ambitious, more outrageous, more…Queen.

But what did that even mean? Freddie thought he knew and he wanted to show his collaborators, so he took drummer Roger Taylor and producer Roy Thomas Baker to London’s Tate Gallery to have them gaze upon Richard Dadd’s The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke.

In later years, “complex” is the word Taylor would use to describe the Victorian-era painting. He could just as easily have called it fantastical, “mad,” bursting with ideas. Yet its fantastical vision was compelling and, in its way, understandable. In short, The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke was everything Freddie wanted the band’s next album to be. Queen II, released 50-years-ago this month, would do with sound what Dadd did with paint.

The picture stands on its own, but Mercury likely mentioned at least something of the Fairy Feller’s backstory to Taylor and Baker. He might have brought up the fact that it was painted while Dadd was a patient/inmate of Bethlem (a.k.a. Bedlam) Royal Hospital. Or perhaps that the reason Dadd was placed in Bethlem in the first place was that he had killed his own father. Because the god Osiris told him to.

Prior to that unfortunate turn of events, Dadd had been a painter on the rise, a member of a group of young British artists known as “The Clique.” He was just starting to find success with some early fairy-themed works, when the opportunity arose to join Sir Thomas Phillips on a trip through Europe and the Middle East, working as a traveling illustrator.

The 10-month trek was taxing, and somewhere along the way Dadd started to crack. He found it hard to control himself, believing that he was receiving directives to cause others — including Pope Gregory XVI, whom he saw while in Rome — physical harm. Initially, a reported sunstroke suffered in Egypt was blamed for his strange behavior, but the more likely cause was that Dadd was schizophrenic. The demanding journey took an illness that had been dormant and brought it to the surface. The real tragedy (well, other than the soon-to-be committed patricide) is that Dadd realized what was happening and yet was powerless to stop it.

After Dadd finally returned home to England, his friends became alarmed at his eccentric behavior. He kept painting and, at times, even seemed like his old self. But inside he was continuing to fray. Only Robert Dadd, his devoted father, refused to believe that his talented son was dealing with anything more than a temporary ailment that would soon be overcome. Eventually though, Robert enlisted the opinion of the psychiatrist Dr. Alexander Sutherland, who deemed Richard dangerous and in need of hospitalization. In August 1843, two days after the advice was received, the son stabbed the father to death during a walk in Cobham Park. Osiris was real, after all, and his commands were law. For the rest of his life, Dadd claimed he was just following orders.

How much Dadd’s malady influenced the creation of The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke is debatable. On the one hand, it takes discipline to paint a masterpiece. On the other, the work is undeniably strange.

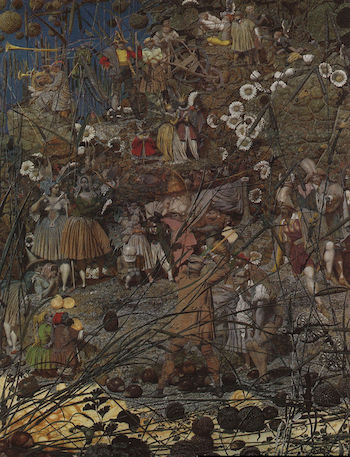

The oil on canvas that would eventually hang in the Tate depicts a gathering of fairy folk around a “feller,” who holds an ax with no blade above his head. He is about to split a hazelnut in half (or he would, if he had a blade … Dadd was transferred to the newly built Broadmoor State Criminal Lunatic Asylum before he had a chance to complete the work). The idea is that once the nut was cracked it would be used to make a carriage for Queen Mab, who is also present in the scene.

Elsewhere in the painting, there’s an arch-magician, who presides over the affair. Also on hand is the pedagogue, or critic, who will judge the job done by the feller. Other witnesses include a soldier, sailor, tinker, tailor, ploughboy, apothecary, and thief of childhood rhymes. There’s also a tatterdemalion and a junketer, a politician, and a satyr, peeking under a girl’s dress. If this weren’t enough, Oberon and Titania, a fairy dandy, and a dragonfly playing a trumpet are also present. It’s a kitchen-sink-piece of fantastical art, and Dadd squeezes everything into a canvas less than two feet tall and not even a foot and a half across.

Richard Dadd. Fairy Fellers’ Master-Stroke. 1855–1864. Oil on canvas. Photo: WikiCommon

This is exactly what Freddie Mercury had in mind for the band’s next move. When it came to recording Queen II, no musical idea would be too wild, no production technique too far out. More was more and nothing was off limits. “Anything you want to try,” he told producer Baker at the Tate, “throw it in.” One way or another, they’d make it all fit.

And so they did. While the band proudly declared (as they would on record sleeves throughout the ‘70s) that “nobody played synthesizer,” every other instrument was on the table. The finished album featured tubular bells, Stylophone, castanets, harpsichord, marimbas, and a gong, along with the group’s more traditional guitar, piano, bass, and drums (no wonder Over the Top was floated as a potential title). On at least one of the album’s more extravagant tunes, tracks were layered on top of each other until the recording tape became transparent. If they added anything else, the record would have literally fallen apart.

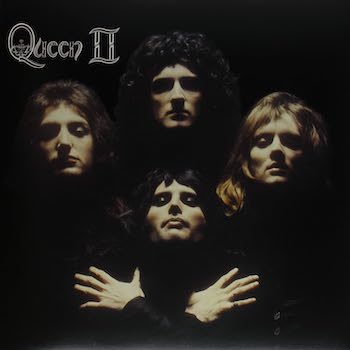

Clearly, Queen II aspired to grandeur. The cover, an iconic photo by Mick Rock showing the band dressed in black against a background of the same color, looking like a four-headed monster, ensured listeners would recognize ambition before they even heard a note. Rather than appearing on “Side 1” and “Side 2,” the songs were assigned to “White Side” and “Black Side,” with the former comprised of four cuts by guitarist Brian May (plus one sore thumb of a track by Roger Taylor that doesn’t fit at all) and the latter featuring six contributions from Mercury. There are epics (“Father to Son” and “Black Queen”), ballads (“Nevermore”), rockers (“Ogre Battle”), and for the first time in Queen’s career to date, a hit (“Seven Seas of Rhye”).

In the most obvious and direct tip of the cap to Dadd and his influence on proceedings, there’s also Mercury’s “The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke,” perhaps the Queen II-iest of all the tracks on Queen II. Like the artwork for which it was named, the song is a tight composition stuffed with surprises. In just over two and a half minutes, harmonies are stacked, odd time signatures are utilized, and the aforementioned harpsichord is deployed. Vocals pan from one speaker to the next, making the song “one of our first major experiments in stereo I think,” Taylor recalled during a 1977 interview with the BBC.

“Could have only been a studio creation,” is how May quite rightly summed up the song for Mojo in 2019. Unsurprisingly, the tune was only very rarely performed live.

As for the lyrics, in the same BBC interview where Taylor noted the song’s use of stereo, Mercury shared that he did “a lot of research” on The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke, and that he wanted what he sang to describe “what [he] thought [he] saw in it.”

When asked directly by interviewer Tom Browne what he discovered in his research, Freddie sidestepped the question, unwilling or unable to shed any more light on the song’s genesis.

“Um, it’s just because I mean I’ve come through art college and things like that,” the songwriter replied, “and I just, I basically liked the sort of artist, and I sort of liked the painting, and I thought I’d like to sort of write a song about it.”

What Freddie actually learned, even if he wouldn’t share it with the BBC, is that Dadd wrote a poem that describes the characters and scenes contained in The Fairy Feller, and Mercury’s lyrics can be traced back to this work.

Dubbed “Elimination of a Picture & its subject – called The Feller’s Master Stroke.” Dadd wrote the poem in 1865, shortly after his transfer from Bethlem to Broadmoor (where he’d lived the rest of his life, dying there in 1886), yet its existence was unknown to scholars until the early ’70s. Once uncovered, David Greysmith quoted from it in his 1973 biography Richard Dadd: The Rock and Castle of Seclusion, as did Patricia Allderidge, first in her September 1972 Sunday Times Magazine article “Midsummer Nightmare” and later in her 1974 bio The Late Richard Dadd.

That Freddie’s lyrics have their origins in Dadd’s poem is well established. Less explored is how the singer became aware of the poem’s existence in the first place, or where he would have been able to read at least parts of it.

As it turns out, both of the above mentioned biographies were among Freddie’s possessions auctioned by Sotheby’s last September, but “Midsummer Nightmare” was the primary, if not only, source he used to write his song. The Late Richard Dadd can definitely be ruled out, because it hadn’t even been published until after Queen II was released, and while it’s possible the singer referred to Greysmith’s book as he drafted his lyrics, there are certain words and phrases from “Elimination” (specifically “harridan,” the politician with “senatorial pipe,” and a “pedagogue…squinting”) that are present in “The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke,” but are nowhere to be found in The Rock and Castle of Seclusion.

All of these words and phrases, however, can be found in “Midsummer Nightmare.” Though misattributed to Julián Doyle by Sotheby’s, the article, which chronicled Dadd’s life from promising painter to asylum patient, was definitely written by Patricia Allderidge and Freddie definitely had a copy of it.

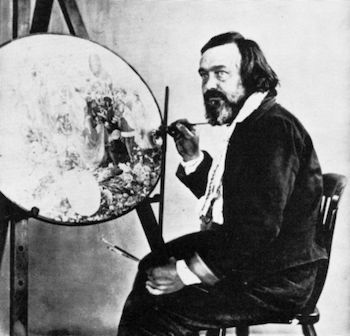

Portrait of Richard Dadd working on the painting “Contradiction: Oberon and Titania.” Photo: WikiCommon

A color reproduction of The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke that Freddie removed from its binding and framed was included in “Midsummer Nightmare,” plus a caption running alongside the picture that identified all the characters and scenes the frontman needed to craft his lines. It’s not hard to imagine Mercury staring at the image and trying to spot Waggoner Will, the harridan, and the rest of Dadd’s motley crew, all the while working out how he could spin what he saw in the picture and read in the caption into something that could roll off his tongue.

It’s of course possible Mercury had other sources as well, but based on available evidence, “Midsummer Nightmare” is the only work he obviously referenced. Whether or not that constitutes “a lot of research” is in the eye of the researcher, though for someone who was famously not much of a reader, that there was any effort at all to understand what was going on in The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke speaks to just how enthralled and inspired Freddie was with Dadd’s work.

In the end, it was a fascination that paid off. Queen II was the breakthrough the band had been looking for, due in no small part to their miming of “Seven Seas of Rhye” (another compact song with phantasmagorical lyrics) on Top of the Pops. The single shot to number 10 in the U.K. charts following the performance, while the album, which was released only after its sleeve was reprinted to correctly identify the group’s bassist as John Deacon, rather than “Deacon John,” climbed all the way to number 5.

Not that any of this commercial success mattered to the rock press. Queen II was “overproduced” the scribes complained. And they were not wrong, but excess was the point. Wounded, the band would reign themselves in (sort of) in the follow-up, Sheer Heart Attack, though they never really surrendered to minimalism. Why should they? Queen now knew who they were and what they were capable of. They had their template and going forward, “over the top” would always be a club in their bag. Thanks to The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke, they knew how to swing it.

(Special thanks to Nicholas Tromans for providing me with a copy of “Midsummer Nightmare,” and helping to crack the nut.)

Adam Ellsworth is a writer, journalist, and amateur professional rock and roll historian. His writing on rock music has appeared on the websites YNE Magazine, KevChino.com, Online Music Reviews, and Metronome Review. His non-rock writing has appeared in the Worcester Telegram and Gazette, on Wakefield Patch, and elsewhere. Adam has an MS in journalism from Boston University and a BA in literature from American University. He grew up in Western Massachusetts, and currently lives with his wife in a suburb of Boston. You can follow Adam on Twitter @adamlz24.

Tagged: “Midsummer Nightmare”, Freddie Mercury, Nicholas Tromans, Queen rock group, Richard Dadd

Interesting article. There are some great songs on Queen II. “Nevermore,” “White Queen,” “March of the Black Queen,” among them. It was the band finding their wings. Brilliant album cover too. My daughter has a poster of it in her room today which shows the timeless appeal of this band.