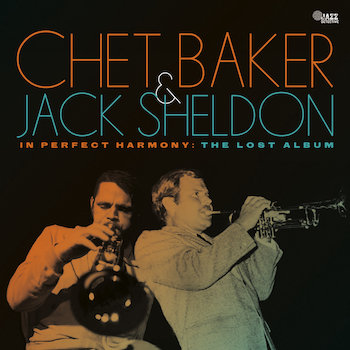

Jazz Album Review: Chet Baker and Jack Sheldon — “The Lost Album”

By Steve Provizer

The music works. The session is among old friends. The rhythm section cooks and every solo holds one’s attention.

In Perfect Harmony: The Lost Album. Chet Baker and Jack Sheldon – trumpet and vocals, Jack Marshall – guitar, Dave Frishberg – piano. Joe Mondragon – bass, Nick Ceroli – drums. Recorded 1972, Tusin, CA

I find Chet Baker and Jack Sheldon fascinating as individuals and as a binary system, in eccentric orbit around each other. Check out links to my other Arts Fuse pieces on the pair below.

Much of my musing has focused on why Baker became an icon of cool, while Sheldon, though he had a successful musical career, never achieved iconic status outside the jazz world. I chafe against the most glib answer — which, unfortunately, may be the most salient — appearance. Until his drug taking began to overtly ravage his body, Baker was chiseled, swoon-inducingly handsome. Sheldon, on the other hand, looked like a slightly elfin, twinkly-eyed version of your high school math teacher.

Baker came from Oklahoma and Sheldon from Florida (his mother chased his reluctant dad across the country). They were almost the same age and both ended up in Southern California. Both were bad boys: they caroused and sat in at clubs together in the early ’50s. Eventually Jack cleaned up his act but, as we know, Chet never did. For both, Bop was foundational, though Baker took an understated approach while Sheldon was likelier to erupt into virtuosic forays. Sheldon didn’t start singing publicly until the ’70s, while Chet Baker Sings was released in 1954. As vocalists, they inhabited different planets.

As time went by, Chet’s musical introversion — especially in vocals — only deepened. His public presentation, certainly whenever I saw him, was relaxed, but no-nonsense. On the other hand, if extroversion can expand over time, Jack’s did. He was a gifted, genuinely funny (and often dirty) humorist — another reason he didn’t acquire the kind of mystique Baker did. Comic performers seldom are mythologized the way “serious” actors are. Ironically, until the end of his life, Sheldon practiced daily and worked hard to improve his playing. He also developed his singing and was able to access a wider range of vocal dynamics. Baker was content to use his enormous natural gifts; his voice and playing remained largely unchanged over the years.

Both lives were rife with tragedy. Baker’s was mostly self-inflicted, or at least, drug-propelled, while Sheldon’s was inflicted from without. Within a fairly short period, his mother was killed by a garbage truck, his son died of cancer, and a daughter in a plane crash.

Sheldon never shared his grief. He was the entertainer, eager to please audiences yet willing to take risks in his playing. Baker was more cautious, yet more precise as well; occasionally letting bits of his personality peek through the performance facade. These occasional bursts of candor seduce the listener into thinking the performer will reveal himself — but he never fully does.

This session was recorded in 1972, one year before it’s generally thought Baker undertook a “comeback” after the loss of his teeth in a fight. The recording was Sheldon’s idea, his way of helping his pal get back into the scene. In order to make things as low key as possible, it was recorded in an out-of-the way studio in Tustin, CA. Fifty years later, tapes of the session were unearthed from the garage of the session’s guitar player, Jack Marshall.

Chet Baker. Photo: Bandcamp

There are 11 tracks in this album and I’ll take a closer look at some representative examples.

Sheldon sings “This Can’t Be Love” with an approach that is partly droll, partly satiric, partly romantic — it is the hybrid space his vocals often inhabit. Chet then sings with just bass accompaniment; it’s as though a gauzy layer of silk has been thrown over the microphone. He stretches the time in his characteristic way as Sheldon does Chet-like trumpet obligatos in the background. It feels like something else should happen in the song, but they’ve kept the length of almost all the tracks to 2-3 minutes in length.

“Just Friends” is Chet’s vocal. Again, he stretches the tempo; Sheldon accompanies. The latter solos, using the full range of his horn. Sheldon often slurs between notes, and it almost has a vocal resonance — it certainly evokes his own singing. Baker’s vocal takes it out, pushing his voice a little past where it can comfortably go.

“Too Blue” is a Sheldon original, done in a medium up tempo. A short Baker trumpet intro is followed by Sheldon’s vocal, which alternates between intimacy, bringing out the double entendre, and pushing the lyric toward the comically absurd. Both men have a slight twang in their voice. I don’t hear it as specifically midwestern or southern, just the way those accents came about, filtered through the laid back California experience. Sheldon uses some vibrato; Baker mostly eschews. Pianist Frishberg stirs the pot and, in a long vamp out, Baker is joined by Sheldon, who adds a bit more flourish. If Sheldon means to push Baker, Chet doesn’t rise to the bait — or the challenge.

“Historia de un Amor” is a ballad written by C. Eleta Almaran. Sheldon handles the Spanish lyrics well, accenting their romanticism. He occasionally edges into the maudlin, but this may be the impression because of the contrast with Baker, who avoids the mawkish at all costs. Baker plays some simple lines behind the melody, then Sheldon plays the melody on trumpet with small horn fills by his partner.

Chet plays the melody of the Jobim bossa nova “Once I Loved.” His playing is fairly straight — for a chorus — and then he plays jazz on it, maintaining his lyricism for the most part, using the low register effectively — a trademark. In the vamped outro, Baker is joined by Sheldon, who then spins more complicated lines and high end bursts around Baker. Some lively back and forth eventually gets going between them but, for some reason, the producers chose to fade out the track just it was starting to get interesting. As noted, all the tracks are short; I’m not sure what the thinking was behind this. Sometimes brevity is the soul of wit and sometimes it’s the wrong choice.

Trumpeter Jack Shelton. Photo: Bandcamp

“You Fascinate Me” is a Coleman-Leigh tune associated with Blossom Dearie. The song lends itself to a patter song approach, and Sheldon takes up a half sung, half spoken approach, aside from the bridge. Baker comes in with some trumpet background and takes over for the next chorus. His chops sound a little weak here. Sheldon occasionally pushes into a half-yodel in some of his more excited vocals, and he does that here on the coda.

“When I Fall In Love” is the longest track in the set, clocking in at 5:05. Sheldon starts with a trumpet intro, followed by Baker embracing his sweet spot: a ballad vocal. Sheldon enters with some brief, simple trumpet background and Baker finishes the chorus. Frishberg’s piano makes a short transition to Chet on trumpet — here one hears so clearly the congruence between his horn and his voice. Baker comes back in to finish on vocal, and it’s hard to not hear some fluctuations in his intonation. The group plays a nice game of tag with Baker’s voice and Sheldon’s trumpet.

This is the only recorded collaboration between the musicians that I know of and I don’t know why. Perhaps behind the camaraderie there was something else going on. They were running buddies, yes, but as Sheldon says, he had to work like a dog to play and Baker could just do it. They were both drinkers and pot smokers, but Baker eventually turned to harder drugs. It’s almost as though when Baker hit rock bottom, his friend offered the opportunity to reconstruct and reconfigure their relationship. According to the album notes, Sheldon said to Baker: “Just think, Chetie. If we do an album together, you’ll only have to play on half of it.”

Whatever the subtext, the music works. The session is among old friends. The rhythm section cooks and every solo holds one’s attention. There may be a few weak moments in Baker’s playing and some strain in his singing, but the yin and yang of their teaming up, 50 years after, is still compelling.

Jazz and the Single Trumpet Player

Jazz Remembrance: Jack Sheldon

Jazz Commentary: Chet Baker — The Climax of Cool

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Very fluent.

Nice review. As an add — I have an old Jack Sheldon LP very much of the 1950s West Coast school that Chet Baker appears on.

It’s not on his Discogs page but here is the one:

https://www.ebay.com/itm/303953426685

Enjoyed your album review — good stuff.

As an aside, Baker did appear on an earlier Jack Sheldon LP, one very much of the West Coast 1950s Cool variety.

Don’t see on Jack Sheldon’s Discogs page but it’s here:

https://www.ebay.com/itm/303953426685

Thank you. That’s interesting. It’s two separate sessions, with Baker on the latter. I could only find one track on line w. Baker, and he doesn’t solo.

Wonderful piece, Steve! I love both the info and the song analysis. I do have a question, though. Why do you say that the common answer concerning Chet Baker’s popularity beyond the realm of jazz-heads — his looks –is a glib answer. Looks don’t count as much among pure jazz fans, true. But one can safely state that Miles Davis would’ve sold far fewer discs if he didn’t exploit his perfect visual image over multiple decades. Baker wasn’t just good-looking. He was — no exaggeration — a gorgeous 1950s matinee-idol. Like Miles, the music fit the image. Beauty isn’t the glib answer for his appeal, it is the true and only one. (Plus he sang… with a limited voice — attaining a convincing lovelorn ennui.) His looks were movie-star spectacular, like a deeper, moodier, more chiseled version of Tab Hunter. It wasn’t that he was handsome FOR a jazz musician! He was a perfect 1950s Hollywood glamour boy , but with more soul, more of a searching, broken-hearted quality. For females he was a dreamboat. For gay males, ditto. For straight male jazz fans, he was an ideal of what they wished they looked like. And, of course, for folks who only occasionally listened to jazz… he was one of the few known entities in jazz. Put in few words –he had cross-over appeal.

Unfortunately, your article had no dreamy 1950s photo of Baker, just one from his utterly ruined heroin-addict 1970s, And even in that period, disgusting as it was, he had an appeal to some: heroin chic. The semi-fake documentary, “Let’s Get Lost” about Chet, was directed by fashion photographer Bruce Weber, and he had the gall to place a dying Baker in a convertible and hire a batch of pretty female Los Angeles models to act like their were enamored of this near corpse of a man. That brought heroin chic to a new obscene level! Baker died before the film was released. In the ’50s, when jazz was selling pretty well but not a the top of the pop charts, Baker broke through with pop-star appeal. Put it this way: 1950s Chet and 1950s Miles both played love ballads that a non-jazzhead could feel deeply. Both men outsold Clifford Brown, who excelled at heartfelt ballads. Brown was no looker. Baker was. And Miles sold a hip image and had ultra-cool good looks to spare. Even in jazz circles, looks once possessed some appeal. Even jazz-fans are human!

Thanks, Dan. In the article I say that I chafe against looks explaining Chet’s crossover appeal. I know that looks have always played a part in audience response to an artist, but the part it plays seems like it’s on a steep upward curve. Now, with AI and other technologies, we can pretty much make anyone look and sound like we want. The 10,000 hour investment in an art is not necessary to crank out a consumable product. What is lost in skirting this level of investment in time and energy is innefable but palpable.

This will play out over time, and I don’t think it will end well. I fear art will follow the course politics has taken and we will get what we deserve.

Nice review! I bought this vinyl and for whatever reason I play it all the time. It’s live session jam feel and solid drum and bass add a dimension that just makes it really fun to listen to. Plus as a child of the 70s Jack Sheldon singing makes me smile.