Jazz Album Reviews: Moppa Elliott’s New Recordings — His Most Sincere Efforts to Date

By Steve Elman

Moppa Elliott makes eminently approachable music at a very high standard, with great ingenuity and sophistication. He has proven himself to be one of the most inventive and creative composers for small jazz ensemble since Charles Mingus.

Moppa Elliott: Advancing on a Wild Pitch (Quintet) – Disasters Vol. 2 and Acceleration Due to Gravity (Nonet) – Jonesville

Basset-composer Moppa Elliott. Photo: courtesy of the artist

Bassist-composer Matthew “Moppa” Elliott makes small group jazz, and that is about the only reasonable generalization to offer about his body of work. He has chosen such a wide range of materials and such a distinctive approach to them that it is dangerous to say anything definite, because he is likely to confound what’s been written with his next release.

Someone who approaches his releases without any previews may be daunted by Elliott’s eccentricity as a self-marketer (more about that below and in a companion post), but I encourage you to take the plunge and start listening to him, no matter what the trappings of his recordings might say to you. Elliott makes eminently approachable music at a very high standard, with great ingenuity and sophistication.

He is an excellent bassist, mostly playing acoustic on releases so far, and his skill and warm sound on that axe provide outstanding anchors for his compositions. On the amplified one, he is less distinctive, but he knows how to lay down the grooves needed. Over the past twenty years, nearly all of the more than 100 pieces he has recorded have been his own. He has gradually transcended his initial bad-boy persona and has proven himself to be one of the most inventive and creative composers for small jazz ensemble since Charles Mingus.

His two new recordings may be his most sincere efforts to date, and you would not go wrong to sample (and buy) one or both. Both were issued on traditional vinyl (collectors, take note), on CD (where the sleeve notes are almost unreadable), and via digital download on Bandcamp.

For the first time, they shed some of the irony and parody that marked the packaging of each of his earlier projects.

The two releases complement one another nicely. Although nothing Elliott does is “conventional,” Disasters, Vol. II is more straightforward, with a jazz quintet that behaves more or less as you’d expect – even though the front line is a pair of low-register instruments (baritone sax and trombone) and the tunes are intricately structured.

Jonesville, on the other hand, is music for a kind of modern jump band. The lineup is a nonet that plays with an anything-goes abandon – five horns in front, electric guitar (often taking fuzztone solos), piano, drums and electric bass. The repertoire on this one is . . . well, read on.

No matter how interesting Elliott’s music might have been in the past, the way it was presented was either intriguingly tongue-in-cheek (as it was to me from the very first) or off-putting (as it was to many others), with packaging that imitated the jackets of famous jazz recordings, deliberately obfuscatory liner notes, and tune titles drawn from the names of cities and towns in Pennsylvania, where Elliott was born.

(By the way, everything that appeared in the liner notes on those previous Elliott releases served as a warning to a writer about trying to “explain” his work, but words are what I do, and I hope that this post will whet your appetite to listen to what Moppa Elliott the composer has to say musically.)

I have prepared a separate post with a short history of Elliott’s recordings and an overall appreciation of his work, with some more perspective on the two recordings discussed here. If you want to take a deeper dive into his music (which I recommend), have a look at that one.

The total time of these new releases is about an hour The seven tunes on Disasters Vol. II are compact; only one is longer than six minutes. Jonesville is really a sort of EP, clocking in at a bit more than 20 minutes, and he has set himself an even greater challenge there: compressing his ideas and the soloists into tracks that would fit on 45 rpm singles – not one of the seven tunes on Jonesville is longer than 3:40.

But don’t be fooled: an enormous variety is packed within each frame on each of these recordings.

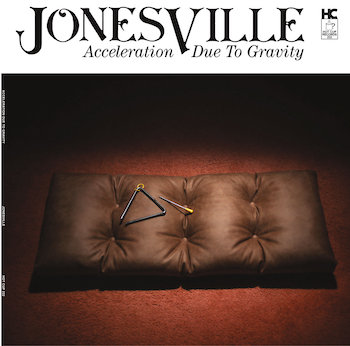

The cover of Jonesville. The triangle is a visual pun on the name of a group in which Sam Jones played bass.”

Jonesville (subtitled Music by and for Sam Jones) is a departure for Elliott, a tribute to one of his heroes, bassist-composer Sam Jones. In a career that lasted only 26 years (Jones died in 1981 at 57), he became a ubiquitous figure on the New York scene, making 12 LPs as a leader and recording with Cannonball Adderley, Oscar Peterson, Cedar Walton, Clifford Jordan, Grant Green, Bobby Timmons, and many more.

The sincerity of Elliott’s tribute extends to the cover picture: a brown button-tufted pad serves as the cushion for an orchestral triangle and the tool used to strike it, both artfully posed. What does that image have to do with Sam Jones? It’s a visual pun. Jones was the bassist in a quartet led by Clifford Jordan, with the other three members (Jones, Cedar Walton, and Billy Higgins) called “The Magic Triangle.”

There are three Jones originals on Jonesville, all given radical transformations, and four Elliott tunes that use shards of Jones’s work as foundations. Elliott says in the notes, “Each one [of the originals] contains snippets of material from Sam Jones’s recordings, altered and expanded often beyond recognition.” Elliott calls the nine-piece group he has assembled for this release (and for an eponymous recording issued on Hot Cup in 2019) Acceleration Due to Gravity.

The four original compositions have a character similar to that of Eliott’s transformations of the three Jones tunes that make up the rest of the release – lots of rhythm (though interpreted freely) and lots of excitement, in snappy sharp-edged boxes. In 2019, Elliott described this group as “a dance band.” If you feel that you can’t dance to the tunes here, remember Dizzy Gillespie’s famous quip: “You can’t dance to it.”

Perhaps “Cedar Run” is the most immediately earcatching of the originals. A rocking foundation, strong trumpet lead from Bobby Spellman, slippery chords, fuzztone guitar fills from Ava Mendoza, soulish backup horn figures, sparkling piano from George Burton, a high-energy baritone solo by Kyle Saulnier (run through an amplifier with a wah-wah pedal), and a sudden ending make it a joyous merry-go-round ride that lasts a bit more than 3 minutes.

But there’s so much more, on these tunes and on the Jones covers. Each member of the nonet gets a chance to shine, and each one makes the most of their solo spots. Trombonist Dave Taylor shows how much he knows of his instrument’s history, with growl and mute stuff that does him proud. Drummer Mike Pride has to hold things together through lots of intricate shifts, and he never loses his footing. And every time saxophonists Matt Nelson and Stacy Dillard play, the tunes go into orbit.

The three covers are noteworthy for how much they vary from the proto-R&B originals.

“Del Sasser” and “Unit 7” are Jones’s best-known originals, both written when he was a member of Adderley’s quintet, but Elliott ignores them here. There are, after all, so many covers of these two tunes that more stabs at them must have seemed like wastes of time to the leader. Instead, Elliott looks to the early years of Jones’s career in early R&B for tunes, and he dusts off three that were originally issued on 45s.

The members of Acceleration Due to Gravity. From left to right. First row: Dave Taylor, Kyle Saulnier, Bobby Spellman; Second row: George Burton, Moppa Elliott, Ava Mendoza: Third row: Stacy Dillard, Matt Nelson, Mike Pride. Photo: Peter Gannushkin and Nathan Kuruna

However, no 45 ever had soloists like the ones in Acceleration Due to Gravity. They play on the beat, float around the beat, ignore the beat, adhere to changes, scream beyond the changes . . . in short, they offer as wide a variety of jazz approaches as you might hear in a night of club-hopping in Manhattan or Brooklyn. Elliott says of his process, “At least one musician is always creating an improvised solo while the music around them repeats through cycles or loops that never recur without undergoing some change.”

In its original form, “Miami Drag” was a slow, rocking 32-bar tune recorded by Sam Jones with Paul Williams, who had a major hit with “The Hucklebuck.” It’s elemental: a riff theme for a small band, with Williams offering a counterpoint figure on baritone sax, followed by a bari solo punctuated by simple calls from the horns. Elliott’s version is recognizable but freewheeling, using the baritone and riff figures, shifting keys frequently and letting the soloists go wherever they choose.

“Choice” is a tune Jones wrote for Tiny Bradshaw in the mid-1950s. Its simple 32-bar format has a rollicking jump feel, with an insistent ostinato bass line reminiscent of many other tunes in the R&B era. Elliott rejects that bass line, along with nearly every other aspect of the original Bradshaw recording. The grooving tempo is there, and some of the basic melody is preserved, but Elliott works a dazzling transformation, shifting keys, offsetting soloists with sharp ensemble passages, and offering what must be a dozen musical surprises in two minutes and forty seconds.

The third Jones original ostensibly comes from Tiny Bradshaw’s book as well. “Stack of Dollars” was a 12-bar riff blues that would be entirely appropriate for Count Basie’s band, with some nice stop-time breaks for the soloists. Elliott’s version is so different that I wonder whether it is a cover of another Jones composition. On Jonesville, the tune titled “Stack of Dollars” has a 32-bar structure and there is a loose island-y feel. This doesn’t prevent the performance from being outstanding on its own, whatever its derivation.

The cover of Disasters, Vol. II. The photo evokes “The Donora Smog,” a tune named after a poisonous combination of steel mill pollution, output from a zinc works, and dense fog that resulted in the deaths of around 70 people in 1948 in the town of Donora, PA.

It would be logical to look back to the last Elliott release (Disasters Vol. I by Mostly Other People Do the Killing [Hot Cup, 2022]) as a precursor to Disasters Vol. II, but the new release is entirely independent from Vol. I, with mostly new music and completely different musicians. Vol. I was played by the rhythm section of MOPDtK, with Elliott, pianist Ron Stabinsky and drummer Kevin Shea. Vol. II is played by a quintet called Advancing on a Wild Pitch, which was introduced on an eponymous recording in 2019 (also on Elliott’s own label, Hot Cup). The name is a nice pun on the members’ interest in baseball and the musical meaning of “pitch.” (Two compositions that appeared on Vol. I are given new clothes in Vol. II, but you don’t have to hear the two versions to appreciate the way they are played in each of the two releases.)

The theme of both releases is man-made disasters that took place in a number of Pennsylvania towns and neighborhoods. The music in each composition does not reflect the disaster that gave it a title. In fact, in the notes on the sleeve, Elliott (for the first time that I know of) says explicitly that his compositions and their names are not related: “I have been titling all of my compositions after cities and towns in Pennsylvania, initially as a way to obscure the link between title and content . . .”

Which does not mean that he is unserious in purpose, or that the titles are meaningless. He describes each of the disasters in the notes, and those accounts make for sobering anti-corporate reading.

The music has a different message, expressed here in the final sentence of one of the paragraphs in Elliott’s notes: “With the ‘Disaster’ compositions, the titles bring to mind the tragedies that befell the residents of these places and the news-tickerlike way we are faced with more and more of these events, often far off, on a daily basis. Yet we, and the places, carry on.”

If I give less space here to the individual performances in Disasters Vol. II, it’s only because Jonesville is so distinctive in Elliott’s work that it deserves special attention. The music in Disasters Vol. II is superbly crafted and intelligently played, with Elliott and drummer Christian Coleman providing sympathetic support throughout. I’ll just point to two rather different tracks to whet your appetite.

The members of Advancing on a Wild Pitch. Left to right: Christian Coleman, Charles Evans, Sam Kulik, Danny Fox, Moppa Elliott. Photo: Bandcamp

“Cobb’s Creek” is in swinging 3/4, with a hard-bop feel. There are two themes – the first in a minor key, ending with five step-up figures and punctuating smears by horns, and the second in a major key, also ending with smears. The minor-major changes underpin excellent solos by pianist Danny Fox and trombonist Sam Kulik, who picks up a plunger for his few minutes. There is no closing head; Kulik elides from his solo into the five step-up figures, and things come to a definitive halt.

If you aren’t paying attention, “Mud Run” may seem conventional, but it’s not. Over an easy swing, Kulik and bari player Charles Evans play Elliott’s tuneful theme in unison twice, with harmony appearing only briefly. The length of the phrases is irregular; you may think you know where they’ll land, but you’ll be fooled. Kulik and Evans then exchange improv spots, following the irregularity of the theme’s bar-lines. Danny Fox has another attractive piano solo, with some out-of-tempo decorations that push the edges of the harmony. A modified version of the theme closes it out, adding some punchy riffs. Finally, there’s a Basieish tag, but Elliott has the horns play four punctuations, instead of the conventional three, for a final ear-fooler.

Moppa Elliott sounds like he and his bandmates are having a great time on these two releases. They passed my personal test for great music: as soon as I had finished listening, I wanted to hear them again.

More:

Nearly all Moppa Elliott’s work is downloadable and buyable on Bandcamp.

Both of these new releases, along with some other Elliott projects, are also hearable on Spotify.

In the first paragraph here, I generalize about Elliott’s music as “small group jazz,” but he has characterized his groups in different ways — notably “dance band” (his characterization of Acceleration Due to Gravity) and “rock band” (a term he used to describe the band in the 2019 Hot Cup release called Unspeakable Garbage). This reflects how wide-ranging his interests are, but I submit that no one will mistake his work for anything other than music built on the various traditions of jazz.

Steve Elman’s more than four decades in New England public radio have included 10 years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host on WBUR in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, 13 years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB.