Fuse Interview: Greil Marcus on co-editing “A New Literary History of America”

The governing idea of “A New Literary History of America” is that it is about a made-up nation and a made-up literature. That means every time an author, a thinker, an actor in our national story sets out to do something that person discovers America for the first time. Each actor in the drama of the American imagination is his or her own Columbus. — Greil Marcus on “A New Literary History of America” (Harvard University Press)

Greil Marcus, co-editor of A New Literary History of America

By Bill Marx

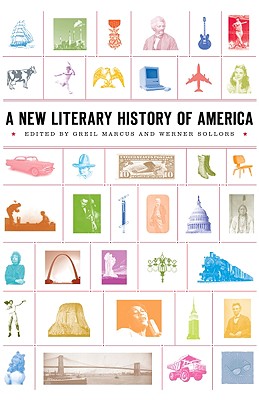

A New Literary History of America, edited by Greil Marcus and Werner Sollors, Harvard University Press, 1100 pages, $49.95

Greil Marcus’s vision that every American book is a voyage to a New Land suggests that he and co-editor Werner Sollors of “A New Literary History of America” must be a couple of hefty Columbuses themselves, reinventing our notion of literary history on the high seas of scholarship.

Made up of over 200 short essays, the book is not your usual bookish chronicle featuring a march of fearless men churning out classics for the edification of the nation. The topics in the nearly 1100 page tome range from cartoons and television to hip-hop and the Winchester Rifle, while the contributors have been chosen to kick-start light via intellectual sparks: Camille Paglia on Tennessee WillIams, Gish Jen on “The Catcher in the Rye,” Jonathan Lethem on Thomas Edison. The guiding principle appears to have been to avoid boilerplate.

No doubt the volume’s eclectic, opinionated vision of the story of American letters, which focuses on the mysterious intersection of events in real life and the imagination, was influenced by the celebrated cultural criticism of Marcus, author of “Mystery Train,” “Weird America,” and many indispensable volumes of music reviews.

I spoke to Marcus at a recent confab about “A New Literary History of America” at Harvard University.

Bill Marx: Why do we need a new literary history of America when some critics would argue that many people don’t seem all that familiar with the old one?

Greil Marcus: Well, if people are not aware of the old literary history of America that is why we need a new one or one that will take in the whole scope of the country and give any interested person an entrée into the story of the whole country. When you have a book with more than 200 hundred essays starting in 1507 and going right up to the present, to the election of Barack Obama, there is something there that will interest anybody.

And the way the book is put together, the way it seems to have either been assembled or seems to have assembled itself, any give piece will immediately spark thoughts and connections and questions. A reader will say ‘I wonder what they had to say about so-and-so … or such-and-such.’ And they will look and find an essay that either directly addresses or touches on that topic; a reader will find himself or herself jumping around until a bigger picture begins to reveal itself.

Marx: How did the project come about?

Marcus: The genesis of the book was that Lindsay Waters, an executive editor at Harvard University Press, had previously edited and shepherded a new history of French Literature and then a new history of German literature, both 1000 page books of 200 or so entries based on moments, events, turning points, drawing on scholars from many different fields. He wanted to do an American volume, but he always knew that it would be radically different from the earlier volumes. It couldn’t possibly restrict itself to literature as such. It will really be a volume about the sources, emanations, and accomplishments of the common imagination of the country itself.

What really makes an American literary history different is that Germany and France, as ideas, cultures, societies, are both extraordinarily old, they are organic societies that developed and took shape long before the emergence of modern nations, whereas in the United States you could certainly argue that the political formation, the invention of the country, the declaration that the country exists, the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, came about through fiat, an invention that the society and its literature develops out of. Just as the country is invented, the literature is self-consciously invented, made up and discovered rather than inherited.

It is also a question of what the American imagination is, assuming there is such a thing. In the course of the book readers will find many essays proceeding on the assumption, attempting to establish there is such a thing and others saying there is no such thing because these essays argue with each other. There is no party line in this book. It has to take in not only poetry and fiction, but also plays, music, political speeches, Supreme Court decisions, inventions.

For example, there is an entry on the Winchester Rifle. And somebody will ask what does that have to do with literature? Well, this is not a history of American literature; it is a literary history of America. That means it is about the imagination, but it is also about a written history. It is literary in the sense that each essay is driven by an attempt to re-imagine a certain turning point in the country’s history, while never losing sight of the story of the country itself.

The Winchester Rifle, while not a literary creation, very quickly and permanently became part of the iconography of the country. And the Winchester Rifle itself becomes a character in countless movies, in countless novels, whether they are dime novels, whether they are Owen Wister’s 1902 novel “The Virginian,” whether they are more serious western novels, it becomes more than a symbol, it becomes something that people use to define what it means to be an American. One of the things being an American means is somebody walking alone toward the frontier carrying a Winchester Rifle. So that becomes part of the common imagination of the country, and that is why we have an entry on it.

Marx: The volume contains no explanatory material about its methodology. Given that you encouraged contention among the contributors, were you and co-editor Werner Sollors editors or ringmasters?

Marcus: We had an editorial board of twelve people and they were mostly younger academics but not completely – Gerald Early, Sean Wilentz, both distinguished professors but also cultural critics who write for general audiences. David Thompson, the great movie critic and film historian, is no longer young but he writes for many different kinds of audiences. We met and we asked each editor to suggest up to 50 subjects that the book ought to cover, asking that the focus always be on when something happened, when something changed — when a book was produced, a speech was given, a journey was undertaken –that left things looking different than they had before, when what had previously been seen as unthinkable suddenly came to seem inevitable. A turning point.

Marcus: We had an editorial board of twelve people and they were mostly younger academics but not completely – Gerald Early, Sean Wilentz, both distinguished professors but also cultural critics who write for general audiences. David Thompson, the great movie critic and film historian, is no longer young but he writes for many different kinds of audiences. We met and we asked each editor to suggest up to 50 subjects that the book ought to cover, asking that the focus always be on when something happened, when something changed — when a book was produced, a speech was given, a journey was undertaken –that left things looking different than they had before, when what had previously been seen as unthinkable suddenly came to seem inevitable. A turning point.

Altogether about 500 proposals were put on the table. Werner and I took it upon ourselves in a completely ruthless and in some ways pigheaded manner to go through the list and strike out about 300, leaving us with 200 selections. Then we presented that act of literary terrorism to the board and said ‘every time you disagree with one of our yeses or nos speak up and we will argue and discuss it.’ And we did it for two solid days from 9 in the morning until 7 at night.

And after mulling over everything, and of course during the discussion new topics emerged, some of which we decided to include, at the end of those two days we had 240 topics. Also, keep in mind that even though the sub-editors had significant expertise in certain fields, everyone had a say on the selections in the book. It wasn’t that the science person was only supposed to think about science, that person could weight in on which particular Poe book to focus on.

After that it was a matter of the editors talking about who should write which essay. Each sub-editor was responsible for between 15 and 20 entries. The sub-editors would suggest who should write which essay. Werner and I would think about that and we might suggest somebody else or maybe we would say that was fine. All in all, W and I were responsible for finally deciding on who would write what, and we were ringmasters in the sense of bringing this all together. But once the essays came in and we began to get a sense of the shape the book was taking the real editing began. And what that meant was being in extremely deep and substantive discussions with each author on how to bring out what he or she wanted to say.

There was never any attempt to get anyone to adopt a particular point of view or to change anyone’s mind or to soften anyone’s position. It was all a matter of making what a given author was trying to say both clear and credible. It was not a matter of saying “would you just drop in a reference here to such and such so this will key into the essay that proceeds yours, we just want to have a bridge here.” It was not done that way.

Somebody said that this book seems to start over with each essay and there is a way in which that is true and that might be a problem for some people, it might be irritating. But for me that reflects the governing idea of the book, which is that it is about a made-up nation and a made-up literature, which means that every time an author, a thinker, a creative person, an actor in our national story sets out to do something that person is discovering America for the first time, each actor in the drama of the American imagination is his or her own Columbus.

Marx: What did you discover as you read through the entries? In your criticism you proffer a strong idea of what America is about. Were those assumptions ever challenged or provoked?

Marcus: For me, I can’t speak for Werner, what was most revealing was the extent of my own ignorance. Again and again and again I would read an essay about something I thought I knew something about, something I knew a little about, something I knew nothing about and I would find grand vistas opening up. I would find treasure chests being opened. I would feel shame and humiliation – how could I have not known anything about this person, this story?

For instance, there’s an essay on poet Wallace Stevens by Helen Vendler, who has written a lot about Stevens and I have read some of what she has written and I have read Stevens, well I thought I had read Stevens but I hadn’t. It was in her entry on Stevens that I caught for the first time the special beauty of what he created and the way in which everything he wrote was unfinished, that he left the door ajar for the next poem, which might or might not be written.

Yet in spite of such historical or geographical allusions, much of Stevens’s poetry of America never identifies its country of origin at all. Instead it puts the problem of an America art abstractly, as in the poem “Somnambulisma,” where Stevens imagines a desolate land that never acquired an art of its own, that never produced a restless hovering bird of the imagination, a land whose inhabitants never were granted a vision of themselves though the “pervasive being” of art.

Without this bird that never settles, without

Its generations that follow in their universe

The ocean, falling and falling on the hollow shore,Would be a geography of the dead: not of that land

To which they may have gone, but of the place in which

They lived, in which they lacked a pervasive being.===========================

(excerpt from Helen Vendler on Wallace Stevens’s Collected Poems in A New Literary History of America)

That’s another idea that surprised me. So many of the entries in this book, particularly the literary ones, rather than music or Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address, or Grant’s “Memoirs,” are filled with suspense. You are reading and you think ‘My God, this might not get written.’ You know the book was written and that is why the entry is there, but as the process of creation is described, as you enter into the writer’s struggle with his or her material, you realize this didn’t have to happen. You get a sense throughout the book that almost nothing, large or small, in our story had to turn out as it did. And that may be true of any nation in any time and place, but I don’t know that it has ever come alive from beginning to end as it does in this book. When each essay starts the story of the country all over again one of the things that means is that everything is at stake, even in the tiniest piece of work.

Marx: I assume you have already heard from readers or commentators who object that some authors have been left out. Talk about how artists were included and excluded. Is there anyone who is not in the volume that you regret leaving out?

Marcus: We knew from the start that this was never meant to be an encyclopedia. It is meant to be a kind of epic, I suppose a collective epic. We never attempted or thought we could include everybody. And we didn’t want to. And some of our exclusions and inclusions are arbitrary.

For example, one of the last essays in the book is mine on the Richard Powers novel “The Time of Our Singing.” I would stand on the claim that that is the great novel written by an American in the last 20 years, maybe farther back than that. The book specifically addresses the American argument about how the nation came to be what it is, whether or not the country even exists, a country that betrays all of its own promises. Does our nation exist at all, that is the question raised in that novel.

For example, one of the last essays in the book is mine on the Richard Powers novel “The Time of Our Singing.” I would stand on the claim that that is the great novel written by an American in the last 20 years, maybe farther back than that. The book specifically addresses the American argument about how the nation came to be what it is, whether or not the country even exists, a country that betrays all of its own promises. Does our nation exist at all, that is the question raised in that novel.

It is not a political or didactic novel, it is a story about people and it is a tragedy, one whose last page will leave you smiling through your tears. And so there is a specific entry on this novel and there is nothing on John Updike, nothing on Don DeLillo, and nothing on John Cheever. Well, I would argue that this novel outweighs the life’s work of those writers. But we didn’t have that discussion on those terms – it was we want that book in this book, so it is here.

Readers will draw their own conclusion about what is in and what’s out, but the book is not a club, it is not a matter of who we want to have lunch with, who dresses well. It was a matter of trying to find entries that would strike sparks off of one another. The last couple of days in the midst of this conference we are having on the book people have asked about this and that, and there have been a couple of things that people have brought up that made me think, ‘we really should have done that, I feel terrible about this.’

The thing I feel worst about is that somebody mentioned that there is no entry on “Mad” magazine. And in terms of something that affected the sensibility of generations, and not just in the United States, that broke the dam of the 1950s, that introduced the notion that anything could be treated with disrespect, derision, suspicion, and contempt, that there were no sacred cows, that was a story we missed. “Mad” was shocking yet its subversion was pursued with such glee and delight by Will Eisner and some of the other creators. “Mad” is mentioned in the book but I would have liked to have seen the Mad world in there specifically.

So as Werner and I wend our way toward the ends of our lives I am sure we will have many regrets. People will say, ‘well, you are going to do a Volume Two of “A Literary History of America,” aren’t you?’ Somebody else will do Volume Two.

Tagged: A New Literary History of America, Greil Marcus, Havard University Press

Is this book as much fun to read as the interview makes it sound? Or as the cover promises (great cover!)?