Book Review: Bora Chung’s “Your Utopia” — A Deep, Rich Well of Imagination

By David Mehegan

The stories in this collection are uneven, although to my mind the beauty and brilliance of the best outweigh the others.

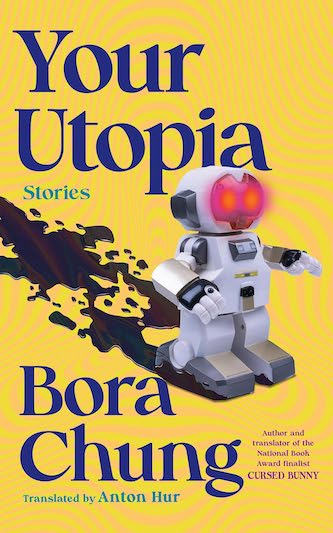

Your Utopia: Stories by Bora Chung. Translated, from the Korean, by Anton Hur. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. 241 pp. Paper. $18.95.

The eight stories in Bora Chung’s Your Utopia, like those in a previous collection, have been variously categorized as comedy, horror, science fiction, fantasy, though surprisingly seldom as social and political commentary. Such adjectives as spooky, funny, gross, haunting, terrifying, uncanny, chilling, powerful, disturbing, and unnerving spill from reviews. Rightly so. One can easily imagine Hollywood leaping to make a movie of one or two of her stories, though the extensive publicity campaign described in the uncorrected proof makes no mention of film rights. (It does promise a “buzz campaign” and “extensive influencer outreach.”)

The eight stories in Bora Chung’s Your Utopia, like those in a previous collection, have been variously categorized as comedy, horror, science fiction, fantasy, though surprisingly seldom as social and political commentary. Such adjectives as spooky, funny, gross, haunting, terrifying, uncanny, chilling, powerful, disturbing, and unnerving spill from reviews. Rightly so. One can easily imagine Hollywood leaping to make a movie of one or two of her stories, though the extensive publicity campaign described in the uncorrected proof makes no mention of film rights. (It does promise a “buzz campaign” and “extensive influencer outreach.”)

Born in 1976, daughter of two dentists, Korean writer Bora Chung earned a master’s degree in European and Russian Studies from Yale and a PhD in Slavic Literature from Indiana University. She has taught at Yonsei University in Seoul, where she lives, and has translated Polish and Russian literature into Korean. Meantime she has written three novels and three short-story collections. Her only previous work available in English, also translated by Anton Hur, was Cursed Bunny, a book of stories that burst on the international English scene in 2022 when shortlisted for the UK’s International Booker Prize and last year longlisted for the U.S. National Book Award for translated literature. It won neither but garnered plenty of attention.

Most of these tales are strangely unsettling (another adjective!), each told by a first-person human or humanoid robot narrator in the plainest of styles, conveying a sense that the seemingly weird goings-on are perfectly normal and completely understandable.

“The Center for Immortality Research” is the most overtly comic, told by a low-level functionary in the private institute who is tasked with helping to arrange a celebration of the group’s 98th anniversary by inviting a celebrity actor to make an appearance. Most of the story is taken up with the detailed accounting of her frustrations with internal bureaucracy as she works on the project. The unnamed narrator (another Chungian feature: no one in the book has a name) could be any overburdened, unfairly treated underling in any business or government agency. Sometimes work-life is hell, to be sure, for the proletariat. The event turns out to be a disaster, and we know what that normally would mean. But neither the functionary nor anyone else in the organization will leave or be fired for a startling reason that we are matter-of-factly told on the last page.

“The Center for Immortality Research” seems like everyday life, but the second story, “The End of the Voyage,” takes us far from Kansas. Though it starts on earth, most of it takes place in a spaceship launched into space with a crew chosen to escape a raging plague and, sometime in the future, if possible return to restore humankind. The disease has one symptom: an irresistible impulse to kill and eat other people. It starts in a small Iowa town when members of a family fall upon and eat one another and eventually spreads throughout the earth. The narrator, another nameless woman, drily explains all that has happened. Her job is to keep in touch with earth and report what happens on board. Soon there is no answer from below and the conclusion is obvious. To her there seems no hope. Where can the spacecraft find safety?

She makes one friend in the crew, not a lover, just a friend named “that guy.” They talk about their lives and families and philosophy. All the others aboard are scientists or medical researchers who talk only about STEM. Inevitably, the disease shows up onboard. Promptly, crew members and others greedily attack and devour one another, until only the narrator and “that guy” are left. He proposes to bring the ship back to earth, which she thinks is madness and resists. But he tricks her into it. When they arrive and find nothing alive, he says to her, “Hope exists if you think it to existence. If you don’t have any, you can just make it up. And we’re here, together. … We can be each other’s hope. We’ll start everything from the beginning. We’ll reconstruct humanity. Create new meanings. Us two.”

It would be pretty to think so, but this is Chungland, far more sinister than Greeneland. I can see the movie now: Night of the Living Dead Meets The Martian.

In “A Very Ordinary Marriage,” set in Korea, a man becomes disturbed at his wife’s mysterious phone calls. He overhears one – it is in a strange language that sounds unearthly. Of course it is, and gradually she confesses the truth of who she really is and where she is from, and his place in the assignment she has been given. She warns him of what will happen to her if her disclosure is found out. No surprise: no happy ending.

Bora Chung — a writer rich in ideas. Photo: courtesy of the artist

Perhaps the most humane and non-bizarre story is “Maria, Gratia Plena.” Using advanced scanning technology, a specially trained technician is assigned to read the images in the memory stored in the brain of a hopelessly comatose woman. Part of a violent drug gang, the woman had taken an overdose from which she cannot be wakened. The chief investigator is trying to find evidence against her collaborators. The technician’s job is essentially to see past events through the eyes of the woman’s memory and report to the investigator. Inevitably, though, as the technician sees this life (and we see it too), she gains increasing understanding and compassion for the torments of the woman’s past, especially the extraordinary family violence of her father. She begins to think the woman might actually be innocent.

What is that line about not being able to understand another person’s acts and decisions without having “walked in her shoes”? Yet this tale reminds us that even in so doing, tapping into the true experience of another’s life is limited. “There’s no way of knowing which scenes stored in her brain are real and which are dreams or hallucinations,” the narrator thinks. “The human brain does not differentiate between storage spaces for experience and fantasy.” All that is clear is that this brain is a warehouse of fear and sorrow.

In the title story, “Your Utopia,” and “A Song for Sleep,” the narrators and protagonists are robots, and we are not surprised when they prove to be more humane than most humans.

The stories in this collection are uneven, although to my mind the beauty and brilliance of the best outweigh the others. The last two, “Seeds” and “To Meet Her,” have a dashed-off, not fully realized feeling. In the first, a bunch of trees in a forest fight back against human exploitation of Nature. The narrator is an oak tree. In the last, an old woman is injured by a terrorist attack while standing in line to meet a famous, apparently transgender author. Eventually she recovers enough to get in line again at a subsequent appearance. There is a strong political theme.

In a curious “Author’s Note: The Act of Mourning,” at the end of the book, Chung explains the hurried genesis and real-life background of “To Meet Her,” and writes, “I hope my readers find it acceptable, … but a part of me does wonder if I’m only messing things up more for the real-life person the story is based on, regardless of my intentions.”

Bora Chung is a writer rich in ideas with an impressive power of controlled narration and tone. Everything is thoughtful and quiet, even amid horrifying details. There is doubtless more richness lurking in her deep well of imagination. However much new writing is to come, at least we can hope to read English versions of her other four previous books.

David Mehegan is the former Book Editor of the Boston Globe. He can be reached at djmehegan@comcast.net.

Tagged: "Your Utopia: Stories", Anton Hur, Bora Chung, Cursed Bunny, Korean fiction, horror