Poetry Review: “Wheatley at 250” — Rescuing Her Imagination, and Ours

By Kevin Gallagher

Wheatley at 250 poignantly responds to the poet’s voice and experiences in order to help us understand ourselves in the 21st century.

Wheatley at 250: Black Women Poets Re-Imagine the Verse of Phillis Wheatley Peters, edited by Danielle Legros Georges and Artress Bethany White. Pangyrus Press, Cambridge, 120 pages, $18.

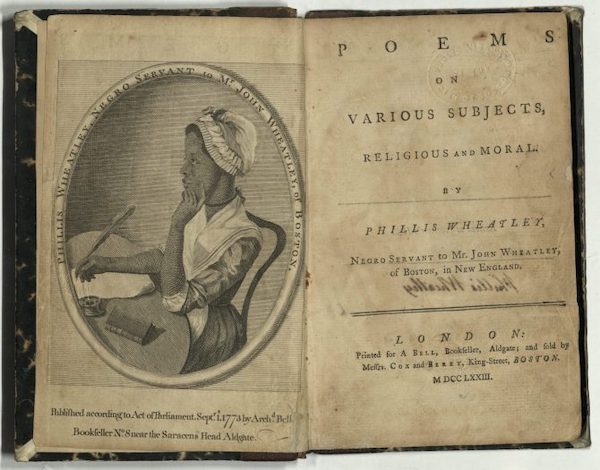

The first edition of Phillis Wheatley’s collection of poems, printed in London in 1773. This copy is signed by Wheatley Peters. Photo: BPL

Today, a little Chimney Sweep,

his face and hands with soot quite Black,

staring at me, politely asked:

“Does you, M’lady, sweep chimneys too?”

So reads Robert Hayden’s “reinscription” of the verse of Phillis Wheatley. As practiced by the contributors to this new anthology, Wheatley at 250: Black Women Poets Reimagine the Verse of Phillis Wheatley Peters, Hayden takes and re-sings the voice of Wheatley, evoking the social concerns of her time while also lamenting and praying for our own. In the beginning of Hayden’s poem in Wheatley’s voice, published in his American Journal (1978), the speaker is en route to London in 1773 to procure a publisher for her first book of poems. She is alluding to her own Middle Passage from West Africa to slavery in Boston in 1761:

I could not help, at times,

reflecting on that first—my Destined—

voyage long ago (I yet

have some remembrance of its Horrors)

and marveling at God’s Ways.

“Phillis” is the name of the boat that took her to Boston. “Wheatley” is the name of the family who purchased her, as a slave at the age of seven, to assist their domestic life at the corner of King and Kilby streets near Boston’s Long Wharf. Mark Peterson, in his study City State of Boston, describes Wheatley’s urban status as a “nobody from nowhere, as lowly a person as it was possible for a person to be in mid-eighteenth century Boston.”

Still, the Wheatleys were a well-to-do and solidly connected family in Boston and England. Phillis was Susannah Wheatley’s servant. She became her owner’s missionary pupil, learning Latin, Greek, and English, and reading poetry. Susannah encouraged Phillis’s development as a poet: she published widely in newspapers and quarterlies on both sides of the Atlantic. Before sending Phillis to London to secure a publisher, however, Susannah summoned Boston’s most prestigious elite to “prove” to them that these poems were written by an African slave. Governor Thomas Hutchinson, future governor James Bowdoin, and John Hancock were convinced that Wheatley’s poems “were (we verily believe) written by Phillis, a young Negro girl, who was a few years since, brought an uncultivated Barbarian from Africa.” Yusef Komunyaka sardonically comments on this belief in his poem “Lament and Praise Song”:

I wonder if the tongues

of that tribunal of good men

quizzing her turned to dust

on pure Latin & Greek.

We are blessed if we can see her

on the streets of Cambridge

in her heroic couplets,

rescued by our imagination.

Boston can claim a long line of firsts in American poetry. Anne Bradstreet was the country’s first published woman poet. Phillis Wheatley the first African-American poet to publish a book in the Americas. The Legos Georges/White anthology is a compelling homage to this pioneer. The volume brings together 20 contemporary Black Women poets (including Tracy K. Smith, Sharan McCallum, and Sharan Strange, co-founder of Boston’s Dark Room Collective). As the editors write in their compelling introduction, each poet has been asked to “reinscribe, translate, or interpret” a Wheatley poem alongside its original and to write an accompanying “compositional note.”

The two co-editors engage with two of Wheatley’s most powerfully relevant poems. In these, Wheatley displays her double vision: she is able to see herself and to suggest that she knows how she is being seen by others. In other words, she mirrors herself looking at her owners and their looking at her. Legros Georges reinscribes “On Being Brought from Africa to America.” In this poem, Wheatley meditates on her paradoxical position as a poet and an enslaved person; she is grateful to be given the language to sing for herself, but uses the opportunity to tell her hypocritical masters that true Christians should not be holding slaves. Legros George’s reinscription amplifies Wheatley’s message:

Mercy you showed

My soul to me, taught

Me to understand that God exists

—That something Greater exists too.

Wheatley’s original hints that her enslavers may not be pure enough to reflect that higher power:

Remember, Christians, Negroes, black as Cain,

May be refin’d, and join the’ angelic train.

Artress Bethany White takes on Wheatley’s other great poem of contrast between Black and white, “To the Right Honourable William, Earl of Dartmouth.” In this poem Wheatley compares the British colonization of America to her own experience as an enslaved person:

No more, America, in mournful strain

Of wrongs, and grievance unredress’d complain,

No longer shalt though dread the iron chain,

Which wanton Tyranny with lawless hand

Had made, and with it meant t’enslave the land.

White focuses on the comparison with slavery, specifically Wheatley’s use of ‘Afric’:

I young in life, by seeming cruel fate

Was snatched from Afric’s fanc’d happy seat.

White elaborates on that sentiment:

Afric, short of course

for Black Sorrow on American shores,

the endless wait for emancipation day

to firmly cast off manacled slavery.

Her 1773 volume Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral was published when Wheatley was an African slave. Just three months after the book’s release, her neighborhood near Long Wharf was drawn into the war zone for American independence. Wheatley’s master was a loyalist and he flew the coop. Susannah remained in the city and died in 1774; her two children passed during the Siege of Boston. Phillis Wheatley found herself having to find a way to survive in war-torn Boston. In 1778, she married a free Black man named John Peters. They had three children — all died as infants. For work, Phillis became a scullery maid at a boarding house; she developed pneumonia and died on December 5, 1784, at the age of 31, after giving birth to her daughter, who died the same day as her. Wheatley at 250 poignantly responds to Wheatley’s voice and experiences in order to help us understand ourselves in the 21st century.

Kevin Gallagher is a Boston-area poet, publisher and political economist. His recent books of poetry are And Yet it Moves and The Wild Goose. He edits spoKe, a Boston annual of poetry and poetics and works as a professor of global development policy at Boston University.

Tagged: Artress Bethany White, Black Women Poets, Black Women Poets Re-Imagine the Verse of Phillis Wheatley Peters, Danielle Legros Georges, Pangyrus Press