Opera Album Review: A Short but Virtuosic Opera from 1786 Receives Its First Recording

By Ralph P Locke

Even without international-caliber singers and players, Giovanni Piaisello’s Amor vendicato works much magic.

Amor vendicato (Cupid Vindicated), Giovanni Paisiello

Sabrina Santoro (Cupid), Roberta Andalo (Alcaeus), Marina Esposito (Daphne), Leopoldo Punziano (Apollo), Valeria La Grotta (Glory).

Giovanni Paisiello Festival, cond. Mariano Patti.

Bongiovanni 2589-90 [2 CDs] 95 minutes.

To purchase the CD, click here. To download or to try any track, click here.

I didn’t know there was a Paisiello Festival, but here is one of his operas performed at the 13th such festival (in Taranto, a coastal city on the inner heel of Italy’s boot). We hear a single performance, from Sept. 11, 2015, but with applause carefully edited out. The work is on the short side, and has only four characters, a chorus, and a fifth soloist (a chorus member, actually) who sings the “licenza” near the end in praise of the king and queen of Naples. The plot comes from Roman mythology, and this occasion was its first revival in modern times. But, as the fine booklet-essay points out, one aria did continue to be performed in recitals for some decades after Paisiello’s death. (The 19th-century novelist George Eliot referred to it in one of her early tales.) It helps that the booklet contains the libretto and a generally adequate translation.

I didn’t know there was a Paisiello Festival, but here is one of his operas performed at the 13th such festival (in Taranto, a coastal city on the inner heel of Italy’s boot). We hear a single performance, from Sept. 11, 2015, but with applause carefully edited out. The work is on the short side, and has only four characters, a chorus, and a fifth soloist (a chorus member, actually) who sings the “licenza” near the end in praise of the king and queen of Naples. The plot comes from Roman mythology, and this occasion was its first revival in modern times. But, as the fine booklet-essay points out, one aria did continue to be performed in recitals for some decades after Paisiello’s death. (The 19th-century novelist George Eliot referred to it in one of her early tales.) It helps that the booklet contains the libretto and a generally adequate translation.

The work is apparently a serenata (though the essay doesn’t use that term): a short opera, with a small cast, intended for performance at a court or private home, with minimal or no sets and costumes. Perhaps the singers even held their scores instead of having to memorize. Like many serenatas, Amor vendicato uses characters and allegorical figures from Graeco-Roman mythology, though, of course, their names are given in Italian. Hence Cupid is called Amor(e), though I use the English equivalents in the header.

The mythological characters play out a game of love that could just as well have been written for humans, or for fairy-tale shepherds and shepherdesses. Indeed, the original libretto calls the work a “woodland fable” (favola boschereccia). Musicologist Bruce Alan Brown reminds me (in an email) that this genre “originated in Tasso’s Aminta — i.e., in a spoken play (for a courtly setting), though one with links to both madrigals and early opera.”

The god Apollo mocks Amor, who gains revenge by making Apollo fall in love with Dafne, who resists him because she is in love with Alceo. As in the famous telling by Ovid, Dafne flees from Apollo and is turned into a laurel tree. But here, unlike in Ovid, Apollo feels remorse, and Amor, now satisfied to have been “vindicated” (as the opera’s title puts it), has a group of cupids break the tree’s bark open and free the nymph. Apollo, as if paraphrasing Aristotle’s principle of the “golden mean,” admits that too much attraction to another person can be harmful, and transfers his affections thenceforth to the laurel tree. In a short concluding passage, the cast and chorus, led by Glory (in Italian: Gloria), praise the rulers of Naples: King Ferdinando IV of Bourbon and Queen Maria Carolina of Austria. Some biographers of Paisiello propose that the serenata was composed to welcome the pair back from their long tour of central and northern Italy.

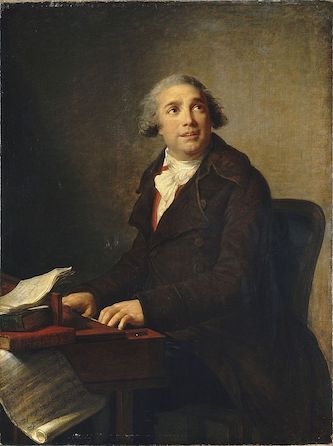

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Composer Giovanni Paisiello at the Clavichord, 1791. Photo: WikiCommon

The work was first performed in summer 1786 as part of an elaborate celebration marking the reopening (after a major renovation) of Naples’s Nobile Accademia di Musica delle Dame e dei Cavalieri (Noble Music Academy of Noblewomen and -men), a hall located near the royal palace and with a membership that rose at one point in its history to 600. The hall was often used for card games, billiards, dancing, and music. This special occasion included not only Paisiello’s serenata but, the booklet explains, “a sumptuous ball lasting until early dawn.”

I have in recent years had occasion to praise new (or first) recordings of two Paisiello comic operas (La grotta di Trofonio; Le gare generose) and one serious opera (Zenobia in Palmira, in American Record Guide, January/February 2018). So I was not unprepared for the delightful arias and duets heard here, which sometimes include prominent concertante passages, especially for oboe. One of the original singers, Franziska Danzi, was married to a renowned oboist, Ludwig August Lebrun, who often traveled with her and for whom the prominent parts for each of them were presumably written. Franziska published compositions of her own. She came from an important musical family — one of her brothers was the Franz Danzi whose works have been much recorded — and, because of her splendid vocal gifts and wide range, was much prized by such prominent composers as Salieri and Holzbauer. The tenor in the first performances was the renowned Giacomo David, future teacher of equally remarkable tenors, such as his own son Giovanni David and G.B. Rubini.

As has been revealed in unprecedented detail in a recent book by Nicoleta Paraschivescu (The Partimenti of Giovanni Paisiello: Pedagogy and Practice), Paisiello taught as well as published widely on the principles of composition (including the art of turning a bass line into a full contrapuntal texture). His skill and sensitivity are on full display here, as is his apparent willingness (analogous to Mozart’s) to shape a vocal part to display the skills of the available performers. The parts for the two sopranos go quite high, into stratospheric Queen of the Night territory. But the one written for Franziska Danzi (Dafne) is even higher and more florid than the one (Amor) for the castrato Francesco Roncaglia. The general style is quite close to that of Haydn, early Mozart, or Cimarosa.

In this recording, the castrato role of Amor is taken by a woman (not, say, a countertenor), as is the role of Alceo (Dafne’s beloved, originally sung by a woman). It took me some adjusting, and careful reading, to realize that the only true female role here is that of Dafne, even though we are hearing three female voices and a single male (tenor). Matters are further confused by the listing of the characters and roles on the jewel case and in the booklet, which switches two of the three “A” names: Apollo and Alceo. (I give the correct assignments above.) Furthermore, in the metadata that may scroll by on your listening machine, the singers’ names that show up are often not the ones we’re hearing in that particular track.

A look at the performance of Amor vendicato (done semi-staged, with a bit of costuming) at the 2015 Paisiello Festival in Taranto, Italy. Photo: GBOPERA

The singers are all capable, which is saying a lot, given how florid the writing is and how high the roles of Dafne and Amor go. They are all native Italian-speakers, so the recitatives are done well. Elsewhere, several of the singers sound impure in pitch, or pressed by a strictly held tempo. The tenor seems unable to trill and shouldn’t have tried. (Maybe just a little mordent, or nothing at all?) The orchestra is a bit scrappy. Unfortunately, the oboist is the weakest of the woodwinds playing here. I found myself longing for a recording of the work with truly stylish singers (the modern equivalents of Franziska Danzi and Giacomo David), a major oboist, and a truly elegant chamber orchestra.

Despite all this, I was delighted to be allowed to hear a fine opera by a major 18th-century composer. If you know only one opera by Paisiello, probably his version of La serva padrona (recorded several times, though not nearly as often as the libretto’s first setting, by Pergolesi), here’s your chance to see what else this skilled craftsman could do. I’d also recommend the more elaborate La grotta di Trofonio, whose plot may have inspired Mozart and da Ponte’s Cosi fan tutte and whose recorded performance (from the Festival della Valle d’Itria in Martina Franca) is classier. Indeed, any of the Paisiello operas that I mentioned would make a fine effect if performed today in a smallish hall by singers with light, clear, flexible voices and good training in Italian. If this sounds like a hint to the New England Conservatory and other music schools with opera programs or even some college with an enterprising student-run opera/theater program … it is! (But make sure you have a first-rate oboist if you’re choosing Amor vendicato!)

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.