Book Review: “The Fine Art of Literary Fist-Fighting” — Punching for Respect

By David Daniel

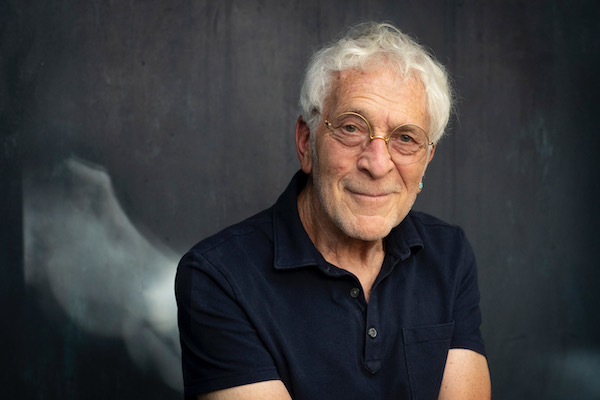

Over the years, Lee Gutkind has been one of the most persistent and impassioned voices making the case for the value of creative nonfiction.

The Fine Art of Literary Fist-Fighting: How a Bunch of Rabble-Rousers, Outsiders, and Ne’er-do-wells Concocted Creative Nonfiction by Lee Gutkind. Yale University Press, 304 pages, $35.

The lengthy title of this book is a précis of its combative arc. It is a chronicle of the pitched battles that took place during a decades-long war of attrition and détente, finally arriving at the culture’s capitulation to the idea of creative nonfiction as a distinct literary form. For anyone surprised that this verdict was ever in question, a remark by Larry McMurtry offers an explanation. “Nonfiction is a pleasant way to walk,” the versatile author of Lonesome Dove and numerous other works once observed, “but the novel puts one on horseback, and what cowboy, symbolic or real, would walk when he could ride?”

The lengthy title of this book is a précis of its combative arc. It is a chronicle of the pitched battles that took place during a decades-long war of attrition and détente, finally arriving at the culture’s capitulation to the idea of creative nonfiction as a distinct literary form. For anyone surprised that this verdict was ever in question, a remark by Larry McMurtry offers an explanation. “Nonfiction is a pleasant way to walk,” the versatile author of Lonesome Dove and numerous other works once observed, “but the novel puts one on horseback, and what cowboy, symbolic or real, would walk when he could ride?”

There is a conundrum in the marrow of a thing that is defined by what it is not. Creative Nonfiction? OK … sooo, what is it? Lee Gutkind admits his frustration at being incessantly demanded to give account of something that was “in the end indefinable.” But that hasn’t stopped him from making a persistent — and often lonely — case that creative nonfiction should be given proper respect, especially by the academy, which for decades ignored it as a literary form on the grounds that there was no covalent bond between “nonfiction” and “creative.” The ironclad conventional line was: works of fiction are fired by the imagination, nonfiction is the product of prosaic research and reporting. This book is a lively dispatch from the “fistfight” waged in the cause of getting creative nonfiction its well-deserved due.

Reaching back centuries for historical context, Gutkind tallies writers whose works were often cohabitations of fiction and nonfiction: from Daniel Defoe’s 1722 novel A Journal of the Plague Year on through to Charles Dickens, Mark Twain, Jack London, Stephen Crane, George Orwell, and others. He highlights two volumes of muckraking journalism that were also works of creative prose that exerted enormous social/political impact: Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, a novelistic exposé of the meat-packing industry, and Rachel Carson’s gracefully poetic Silent Spring, which detailed the ravages of pesticides on wildlife.

Further, Gutkind provides a sensitive discussion of the contributions of women (Nelly Bly, Ida Tarbell, and Martha Gellhorn) and writers of color (W.E.B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells, and Zora Neale Hurston). These were members of groups who were not traditionally welcome in the once prescribed world of professional journalism. They had to fight to be published, and their work offered courageous resistance against sexism and racism.

Understandably, The Fine Art of Literary Fist-Fighting takes a deep dive into the New Journalism of the ’60s and ‘70s. This was the period when writers such as Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, Joan Didion, Hunter S. Thompson, Nora Ephron, and many other trained journalists went beyond the standard formula of “who-what-where-when and maybe why.” They were out to mine the untapped potential of their subjects and stories. Truman Capote’s 1965 “nonfiction novel” In Cold Blood birthed the true crime genre, setting the template for Helter Skelter, The Executioner’s Song, The Devil in the White City, and thousands more. Didion, in essay collections like Slouching Towards Bethlehem and The White Album, gave harrowing, at times elegiac, accounts of what lies under the placid veneers of “ordinary” American life. Among other examples: the long profiles by the durable John McPhee; George Plympton’s wry, participatory embeddings in the action; John Sack’s and Michael Herr’s respective immersions in the war in Vietnam; and a gush of pieces by Norman Mailer on diverse topics: the NASA moon Landing, Muhammad Ali, Women’s Lib, and the Antiwar protests of the late ’60s.

Gutkind devotes deserved space to Tom Wolfe, whose 1963 California hot-rod culture piece in Esquire and a spate of other pieces about pop culture, including 1968’s classic The Electric Kool Aid Acid Test about the psychedelic subculture, made him the poster boy of New Journalism. A natty young Virginian and Yale grad, he skipped about on a high wire of fired-up vocabulary (and typographical trickery: screaming out in ALL CAPS, using punctuation &%#!!, and comic-book epithets “WHAP!” “ZAM!”). His was a “look Ma, I can write” bravura that others raced to emulate. Kurt Vonnegut noted that Wolfe’s special genius was an ability to call attention to himself. This sounds like both praise and a diss — the truth is, Wolfe’s aggressive attitude and prose excited readers.

What Wolfe and others were doing (as did their forebears Defoe and Twain) was to draw on fictional techniques to report on real people and events. Among their rambunctious tactics: structural experimentation, vivid scene-setting and character description, and imaginative use of dialogue, including suggesting the private thoughts of their subjects via interior monologue.

Tom Wolfe in 1997. Photo: Wiki Common

There was some critical pushback, of course. A wealth of new writing was pouring out, much of it via long-form magazine pieces, and the antic playfulness offended (understandably) the sensibilities of journalistic purists. Hunter S. Thompson’s “gonzo” reports in the big rattling pages of Rolling Stone — with Ralph Steadman’s illustrations coming off like blood spatters at the scene of a crime — no doubt bombed readers’ synapses, at times to the point of comic absurdity. The determined allegiance to excess could be exhausting; but there was no denying that new writing had the kind of charismatic appeal that once had been the exclusive domain of fiction.

Still, underlying questions remained. Creative nonfiction: what exactly was one talking about here? Personal essay, memoir, journalism? Some editors tagged it a “bastard form.” Talese’s classic “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold” is a masterpiece of the non-profile; Mailer’s prize-winning account, The Armies of the Night, bears the subtitle: History as a Novel, The Novel as History. There was plenty of head-scratching. John Hersey’s tour de force “Hiroshima” occupied an entire issue of The New Yorker in 1946. That made him one of the progenitors of new journalism, and he was legitimately puzzled by what he had wrought — at what point does nonfiction become fiction?

Beyond the scope of Gutkind’s book, and thus unheralded in its pages, is the crucial role played by innovative editors in the evolution of creative nonfiction. Byron Dobell and Harold Hayes at Esquire, Clay Felker at New York Magazine, Willie Morris at Harper’s, William Shawn at the New Yorker, Victor Navasky at the Nation, Jann Wenner at Rolling Stone, along with editors at the Atlantic, Vanity Fair, Village Voice, etc., were open to change and risk. It was a golden age for creative journalism and the long-form essay, and it opened the gates for later writers. Of course, all of this was before the age of digital.

Author Lee Gutkind — he wants creative nonfiction to receive its due, in academia and elsewhere. Photo: courtesy of the artist

Part of creative nonfiction’s appeal remains its commitment to democratization. Anybody with a story to tell, “no matter how personal and intimate, no matter their background or education,” per Gutkind, “was provided a forum and a vehicle to express themselves and justify and share their lives, their work, and their beliefs.” Inevitably, as an unintended byproduct of this interest in anything (viz the Internet), marched in the bad and the ugly along with the good. The popularity of the memoir, for instance, has spawned a glut of tell-all books, effusions from people with slim-to-nonexistent claims to celebrity or notoriety. And there are outliers who crossed ethical lines: Joe McGinniss writing about Dr. Jeffrey MacDonald in Fatal Vision; Clifford Irving’s “con-fiction” on Howard Hughes; and James Frey’s A Million Little Pieces.

As with any battle report, the chaotic nature of conflict often muddies up a throughline. The rumble becomes a bit of a ramble. And that is true of The Fine Art of Literary Fist-Fighting, though Gutkind does a good job of wrangling a lot of material into 300 pages. Still, there are occasions when words and phrases go bumper-to-bumper, like cars at rush hour on the Expressway. Consider this 77-word sentence: “Tom Bissell, who writes mostly creative nonfiction about travel, once provided an intriguing example of the challenges of the nonfiction writer who tries to do the legwork necessary to be a responsible gatherer of information and piece together all the facts and make the work creative, even when the final product is to the best of the writer’s ability and in their own hearts true and honest, may not, as written, be exactly, upon examination, literally true.”

But these are quibbles. Gutkind has been dubbed the “godfather of creative nonfiction,” a handle about which he seems simultaneously amused and abashed. Still, the rep has given him entrée. Here, with an even hand, he lays out the antipodean camps: traditional teachers and scholars of literature versus a smaller, partisan force claiming that creative nonfiction is a distinct genre. The “fist-fighting” of the title smacks of poetic license: the fisticuffs in question likely took the form of Latinate epithets lobbed from behind cocktail glasses at academic conferences. Still, it is an apt metaphor, and Gutkind is a feisty pugilist. A self-proclaimed lightly credentialed, leather-clad, motorcycle-riding hippie from Pittsburgh, he never got on the officially “approved” path to an academic career. Nevertheless, with Steel City grit, in time he became a full professor and department chair.

Questions remain about where to set the boundary lines between the “creative” and “nonfiction,” style and substance, truthful reporting and falsification. The fact is, literature has always been about blurring borders — truth and fact and invention were seen to be as slippery as eels. What does the familiar disclaimer — “Inspired by True Events” — in books (and on almost everything streamed on Netflix) really mean? Wisely, Gutkind doesn’t waste any of his time punching away at the unanswerable. What his slugging will hopefully do is prompt new generations of writers and readers to find inspiration in the nonfiction of James Baldwin, Annie Dillard, Malcolm X (as told to Alex Haley), Joyce Carol Oates, Susan Sontag, and Gore Vidal.

A regular contributor to the Arts Fuse, David Daniel is author of 10 novels and four collections of stories.

Tagged: Creative Nonfiction, Lee Gutkind, Norman-Mailer, The Fine Art of Literary Fist-Fighting

Great read. An example of the very thing he is writing about. To scoff at creative non-fiction is like saying poetry doesn’t need words. Everything written has a creative center to it. Why should we pretend otherwise?

A lovely, lively , learned, wise review. Itself an eloquent piece that seems to bridge genres. Essay? Review? History? All of the above, surely, and thus three masterclasses in one. Thank you Mr Daniel!

I was thinking that creative non fiction writing was just a blend or amalgam of the historically true embellished with some solid make believe storytelling. But every revolution has its backstory. Daniel lays out a solid cultural etiology that traces how we got to the present day product. I am elated to hear that CNF sprung from the gonzo motif. That leads me to believe that all those rejection letters I received over the years noting my “funky and off the wall” prose may have been misguided.

The academic snobs who malign CNF as an unimportant genre are probably the same effete critics who resented Dylan’s receiving the Nobel Prize for poetry. Literary barriers exit to be breached. Daniel gives us important understanding about how this prosaic revolution unfolded.

This rich article, as pointed out above, reflects the energy highlighted in the material reviewed. It could have been titled “WHAP! ZAM! &%#!!”

Whew!