Theater Review: “Stand Up If You’re Here Tonight” — You Have to be There to See for Yourself

By Martin Copenhaver

This is one of the more engaging pieces of theatre I have experienced in some time.

Stand Up If You’re Here Tonight, written and directed by John Kolvenbach. Staged by the Huntington Theatre Company at the Maso Studio in The Huntington Theatre, 264 Huntington Avenue, Boston, through March 23.

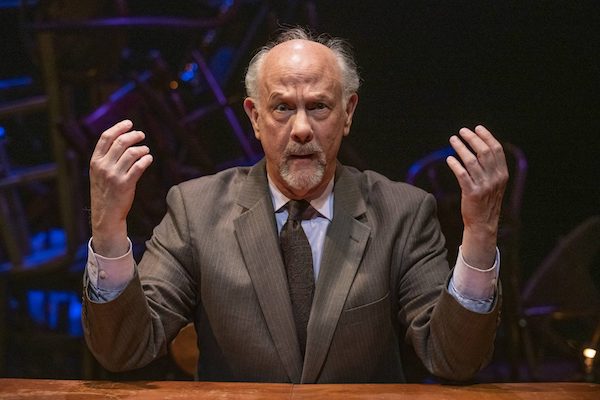

Jim Ortlieb in Stand Up If You’re Here Tonight in the Maso Studio at The Huntington Theatre. Photo: Nile Hawver

Any description of Stand Up if You’re Here Tonight, runs the danger of making it sound unappealing. There is nothing resembling a plot. The monologue is desultory, a seemingly free association of observations, quips, and entreaties. And, worst of all, there is a heavy dose of audience participation. At various points the audience is asked to sigh or clap on cue, to stand or sit, to hum, to read lines, to come onto the stage to answer questions. This is the sort of thing that normally would have me heading for the exit.

Comparisons to other types of experiences don’t help. At first, at least, the play can sound like a self-help seminar. Early on, the protagonist, identified simply as “Man,” tells the audience: “You’ve tried everything. Yoga. Therapy. You juiced, you cleansed, you journaled, you quit smoking, you volunteered, you married, you divorced, you tried monogamy. You ate only rinds for three days and nights. You reached out, you looked within. You have tried. And yet, here you are.”

What is this? Well, quite simply, it is one of the more engaging pieces of theatre I have experienced in some time. By our usual measures — or mine, at least — it shouldn’t work. But it does.

The play begins with “Man,” played brilliantly by Jim Ortlieb, shuffling onto the stage while some audience members are still finding their seats and the house lights are still on. (In fact, the house lights stay on throughout the show, making clear that the audience has a role to play in this drama and that there is no place to hide.)

Then Ortlieb sets up a make-shift desk on saw horses and begins to speak to the audience — haltingly, at first, like a car with an old battery trying to get started on a winter morning. He wonders aloud why everyone came and speculates about all we had to abandon or overcome to get there. Then he begins to pace like a man possessed, by turns assertive and self-doubting, making hilarious observations about the human condition, often immediately followed by poignant confessions about the same. He may be rambling, but it is with a purpose. It soon becomes clear that he has designs on the audience. He seeks connection. He is an evangelist for human relationships.

It would not be accurate to call this a one-person play because the audience is treated as another character. John Kolvenbach, who wrote and directed this play, is known for writing “relationship plays” about love found and love lost. And this is another such script, although in this case the focus is on the relationship between the actor and the audience. It could be entitled, with a nod to Pirandello, “One Character in Search of an Audience.”

Most commonly, the word “audience” is used to describe an assembly of spectators. But “audience” can also connote more of a two-way engagement—as in, “she sought an audience with the president.” In Stand Up, both definitions come into play as “Man” seeks an audience with the audience. He longs for a tangible connection, to have something “schmeared” (his word) between him and the audience.

The primary focus is on the relationship between actor and spectators, but a secondary focus, and a recurring theme, is the relationship between children and their mothers. Along with the frequent references to mothers, “Man” intermittently addresses his own mother in the audience, seeking reassurance and comfort without embarrassment. The cumulative effect creates a mother-haunted play. In Ortlieb’s performance the effect is poignant rather than maudlin, but it is not clear how the focus on mothers fits within the broader narrative.

Inspired by the title of the play, throughout the performance “Man” implores the audience to be fully present: “Be here—that’s the only rule.” No need to worry that the audience will miss the point — the word “here” is repeated throughout, in different contexts but always with the same urgency. By the time he instructs, “Raise your hand if you are here,” you know there is only one acceptable answer to that question.

Jim Ortlieb as Man, a performer seeking an audience in Stand Up If You’re Here Tonight. Photo: Michael Brosilow

Stand Up was written at the height of the recent pandemic. Although words like “Covid” and “pandemic” are not uttered, that period of human disconnection provides the context for a script that addresses the dynamics of a longing for relationship that is characteristic of every era.

Ortleib inhabits the character of “Man” so completely that it is no surprise that Kolvenbach wrote the play with him in mind. It is also not surprising that he has played this role on other stages — including Los Angeles (twice) and Chicago. The character does not seem to be wearing borrowed clothing. The role fits perfectly. At the same time — perhaps due to the inevitable variations that each specific audience provides — Ortlieb brings fresh energy to the role even though he has now played it on various stages for weeks at a time. Kolvenbach says that he wrote the play in response to an unusual request from Ortlieb: “[He] asked me to write a show for him, a show that he could do for the rest of his life.” A tall order. I think he succeeded.

Even before the beginning of the play, this production breaks through the fourth wall. Audience members don’t enter via the main entrance of the theatre, but rather are instructed to go down an alley, up flights of stairs to a space that looks like backstage. It is strewn with what Kolvenbach describes as an “artful pile of junk” — doors, eclectic lighting fixtures, saw horses, a birdcage. It looks more like the detritus of past productions than the stage of a current show.

Moving around the theatre requires that you cross the performance space and then, in the show itself, members of the audience are invited onto the stage. In that same spirit, after the production, the audience is invited back onto the stage to share a drink and to converse with the cast and the playwright/director. Even when the play is over it seeks to facilitate human connection. The fourth wall is nowhere to be found.

As I said from the outset, Stand Up is hard to describe and I am sure I have not entirely succeeded here. So, you will have to see it for yourself. Be there — that’s the only rule.

Martin B. Copenhaver, the author of nine books, lives in Cambridge and Woodstock, Vermont.