Jazz Album Review: Rich Halley’s “Fire Within” — Free, But Still Together

By Michael Ulmann

This doesn’t sound like any other quartet I know.

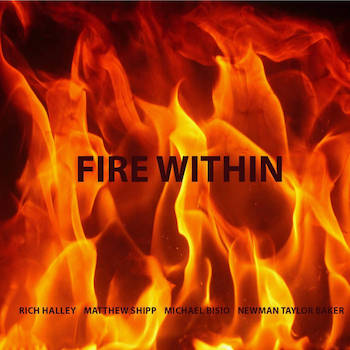

Rich Halley, Fire Within (Pine Eagle Records)

This is saxophonist Rich Halley’s third recording with the quartet of Matthew Shipp, piano, Michael Bisio, bass, and Newman Taylor Baker on drums. They are all stars in my firmament, partly because they seem to understand each other so well. “Fire Within” (the title tune) begins with Halley playing solo in a resonant space. He opens with a series of short, similar phrases, rhythmic devices as much as melodic fragments. He seems to be offering intriguing suggestions as he lays the foundation for the confident performance that will follow. When Halley deviates from his patterns via a downward flurry, Shipp takes that to be a sign to come in. Initially, the pianist plays a phrase that derives explicitly from what Halley has already done. Obviously this is free playing: but soon we realize that the sympathetic sensibilities of the players will keep the music coherent and cogent.

This is saxophonist Rich Halley’s third recording with the quartet of Matthew Shipp, piano, Michael Bisio, bass, and Newman Taylor Baker on drums. They are all stars in my firmament, partly because they seem to understand each other so well. “Fire Within” (the title tune) begins with Halley playing solo in a resonant space. He opens with a series of short, similar phrases, rhythmic devices as much as melodic fragments. He seems to be offering intriguing suggestions as he lays the foundation for the confident performance that will follow. When Halley deviates from his patterns via a downward flurry, Shipp takes that to be a sign to come in. Initially, the pianist plays a phrase that derives explicitly from what Halley has already done. Obviously this is free playing: but soon we realize that the sympathetic sensibilities of the players will keep the music coherent and cogent.

Thanks to the thoughtfulness, as well as daring, of the rhythm section, the improvisatory sections of “Fire Within” take on a vigorous development from Halley’s opening. Shipp solos and then, around six and a half minutes in, he plays a simple rhythmic figure that immediately calls the saxophonist to order: Halley re-enters playing it. Yes, the strong rhythmic phrases act as a stimulus, but they are also a way for the group to structure their improvisations into contrasting sections. “Fire Within” seems to be winding down a few minutes later; what appears to be a kind of resting place turns out to be only temporary. The halt opens up a space for Taylor Baker’s drum solo. When he is ready to finish, the drummer deliberately calms the surface, which invites Halley to return with a dignified version of the melody. The ending seems to slowly unwind; Halley drops out and then the rhythm section eddies still.

Rich Halley is an interesting person. He was born in 1947 and raised in Portland, Oregon, where his dad was a professor of economics at Portland State. He says he spent a lot of his boyhood hiking, fishing, and camping. He took up clarinet when he was 11. When he was twenty he was in Cairo, and from there he went (in 1966) to the University of Chicago. He was at the U of C during the 1966-67 and 67-68 academic years. He told me that he played in a rhythm and blues band called Home Juice during the second of those years. I was also there between 1967 and 68. It was a good time to be in Chicago: Muddy Waters and Howling Wolf were holding forth at their local bars. Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk and others were appearing at the Plugged Nickel, and in Mandel Hall and the Reynolds Club at the University. Various groupings from the then emerging AACM were playing their own evolving, and sometimes mystifying, music. Nonetheless, Halley went back home; he describes himself in those years as investigating both music and the mountains (as well as the jungles of Central America). His interests were wide. From the University of New Mexico, he received an M.S in biology. His specialty was rattlesnakes.

Saxophonist Rich Halley. Photo: Bandcamp

Fire Within consists of five numbers, the longest being the last, the almost sixteen minute “Following the Stream.” The title of the session suggests the quality I hear in the music: its nuanced embrace of passion and control. There’s no choruses of impassioned (maybe hysterical) squealing that seems intended to obliterate the rhythm section. Everything Halley plays refers to members of the ensemble in ways that engage or invite the musicians. Bassist Michael Bisio introduces the second number, “Inferred” with his large, centered tone. In this two-minute solo, he sounds peaceful. He ends with a definitive low note that brings on Halley and Shipp. Taylor Baker taps in the background. That tapping takes on more significance as Halley continues to solo and seems to refer to what the drummer is doing. Shipp plays increasingly thick chords, heavily pedalled. Baker takes this as a sign, I am guessing, to bring out his sticks on snares. Whatever was inferred before becomes very explicit. Shipp drops out temporarily as if to try out a different texture. He returns as an unaccompanied soloist, his two hands in lively conversation with each other.

“Angular Logic” gives us Halley jumping about the horn while Shipp thumps as if to ground the jittery procedure: later the band races temporarily into double time. The shortest cut (at four and a half minutes) is “Through Still Air” and it begins with a barely audible high-pitched and under-nourished wail that continues throughout the song. I believe it comes from the bass. The other instruments, in my reading, are playing almost without tempo through the still air represented by that lonesome wail. The piece ends mellifluously.

“Following the Stream,” by contrast, begins with a quiet drum solo on tom toms, rims…no snares or cymbals for the first minutes. When the hi-hat arrives it comes in quietly — it almost sounds like a reluctant visitor. The cymbals become a part of the conversation and the drum set seems to spread over the sound stage. Finally, after three minutes or so, Halley and Shipp and Bisio enter. Our ears (at least my ears) are still tuned to the drums, however. Soon Halley is exchanging phrases, including the occasional honk, with Matthew Shipp. The pianist’s strategy, or at least one of his maneuvers, is to express himself through increasing intensity, often by repeating the same chord, as if stuck. Then he might float off in untethered single note lines, which supply a different kind of insistence. The band is nothing if not free in the way it investigates its material, but it is also what we used to call “together.” It doesn’t sound like any other quartet I know.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: Fire Within, Matthew Shipp, Michael Bisio, Newman Taylor Baker, Pine Eagle Music, Portland, avant-garde jazz, free jazz