Opera Album Commentary: Maria Callas — Believe Her

By Jon Garelick

A massive, comprehensive new box set once again shows us the diva’s indomitable place in the history of opera.

I once interviewed a musician who told me about sitting in a college classroom with the great jazz saxophonist and multi-instrumentalist Yusef Lateef. The students and their teacher sat in a circle with their horns, taking turns playing a short phrase, no more than four or eight bars. Each student would take their turn playing the same phrase and then Lateef would play. The students listened in silence, but the universal unspoken reaction was, “God damn!”

I once interviewed a musician who told me about sitting in a college classroom with the great jazz saxophonist and multi-instrumentalist Yusef Lateef. The students and their teacher sat in a circle with their horns, taking turns playing a short phrase, no more than four or eight bars. Each student would take their turn playing the same phrase and then Lateef would play. The students listened in silence, but the universal unspoken reaction was, “God damn!”

How could Lateef sound so different from those 10 or 12 students? They were all trained, college-level musicians, playing the exact same phrase, with no improvisation — no musical variation, no added or subtracted notes. But Lateef’s playing of that one simple phrase was in another realm. Was it embouchure, tongue, breath? The attack and flow from short to long notes? Or something about the instrument itself — the reed, the mouthpiece?

Call it that unquantifiable mystery of personal artistic voice. When it comes to the performing arts, how can excellence be imitated or reproduced by others? When the difference between falseness and truth is uncountable, how do you measure greatness?

Those questions were only deepened recently as I delved into the new La Divina: Maria Callas in All Her Roles — a deluxe box set from Warner Classics: 131 CDs, 3 Blu-rays, a DVD-ROM (including libretti and liner notes), and 148-page hardcover book. It’s not a brick, more like a cinder block.

The purported occasion is the great opera diva’s centennial, on December 2 (she died in 1977). One other immediate question the box’s release raises: Who is going to buy it (list price $399.98, though obviously available with discounts)? After all, just about every scrap of this box (except for a new disc of “alternate takes and working sessions”) has been previously available. And it still is — even the recordings of Callas’s legendary 1971-72 Juilliard master classes are on iTunes. And how many people are buying CDs at all?

But that’s probably irrelevant to Warner. How many copies will they sell? Enough. (The box is being released in a limited edition of 3,000.) The important thing is their ongoing investment in the Callas legend. Warner now owns essentially all of Callas’s recorded output — including a valuable trove of live complete-opera recordings that were once traded as bootlegs (and also eventually released in an “official” 42-CD/3 Blu-ray set). For academic study alone, a collection this comprehensive is invaluable.

What’s more, as the old record industry saw goes: Every part of the product sells every other part. Even in an era where “everyone listens online,” sales in physical media — including cassettes — have surged. It’s common practice these days for vinyl or CD purchases to come with a “free” download. If the hoopla around the Warner box whets your appetite but is too extravagant for your pocketbook or your living space, you can “complete your collection” with individual discs — or grab the new vinyl reissue of the 1953 Callas Tosca.

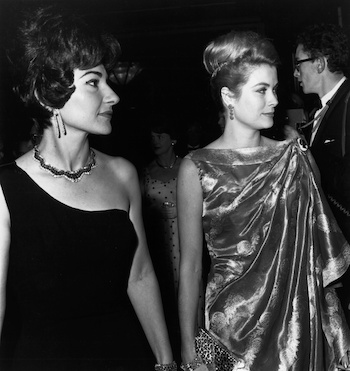

Maria Callas in 1959. Photo: ullstein bild/ullstein bild via Getty Images

Even aside from a core audience of rabid Callas fans (the “crazoids,” as at least one critic has called them), Callas’s towering influence on the history of opera is undeniable. She is credited with almost single-handedly reviving the dormant bel canto Romantic operas of Bellini, Donizetti, and Rossini. She also brought reassessments of the importance of stage acting to the genre. Though Callas’s acting is not often described as “naturalistic,” it was uncommonly precise, expressive, stylized even, but stripped of excess. “I don’t think she did more than 20 gestures in a performance,” said the Italian stage director Sandro Sequi. “But she was capable of standing 10 minutes without moving a hand or finger, compelling everyone to look at her.”

In Callas’s total conception — which she said derived from the score — not only every note, but every word, every gesture, counted. As acting students like to say, she committed. (“We have to have an explanation for these embellishments,” she dryly advises one student about Mozart during a Juilliard class.)

When she died, at 53, Harold C. Schoenberg wrote in the New York Times,

“In the large‐scale operas, such as ‘Aida,’ ‘Norma’ or ‘La Gioconda,’ she sang with such focus of concentration that it could be almost a terrifying experience. Even when her voice was not under control, the intensity of her conception made one forget her struggles with pitch and high notes.”

The conception vs. the voice was an issue for a lot of Callas naysayers who didn’t like the sound of that voice; the variable timbre of her low, middle, and, especially, upper register; the go-for-broke attitude that could sometimes result in loss of control; the “wobble” of her pitch in later years.

As a jazz and rock fan who loved classical music but was a latecomer to opera, I found Callas an acquired taste. Weren’t there other opera singers around with more beautiful voices — Joan Sutherland and Leontyne Price, or, in different repertoire, Lucia Popp and Marilyn Horne, or Callas’s arch-rival of the ’50s, Renata Tebaldi?

But gradually I was won over (not least because of an opera-loving friend’s devotion to Callas and a lot of A-B comparative listening sessions). And whenever I had OD’d on Callas and wanted to move on to other singers (or other operas outside her repertoire), I would eventually come back to her and hear something else in that voice, an emotional quality, that I wasn’t getting elsewhere.

Chalk it up to Callas’s conception, her “almost terrifying” focus.

It’s what still sets her apart. In a conversation some time ago with an opera-loving friend, I made passing reference to one of the major international stars of the day. He didn’t care for her. I was surprised. Why? “I just have never believed her — in any role I’ve heard her sing.

Do you “believe” the singer? In rock and pop it’s called “authenticity,” where arguments can become so heated that in one famous instance, Kurt Cobain of Nirvana accused another Seattle band, Pearl Jam, of promulgating “false music.”

But what about music where it’s accepted as a matter of course that the singer is in some sense playing a role? In my own experience I can easily think of singers who engage my belief — or anyway, suspend my disbelief. There are singers of whom I have specific memories of being transfixed by their delivery of a line of lyrics and music: Rosemary Clooney opening her set at the Newport Jazz Festival with “How are things/in Glocca Morra” and making me feel like it was the most important question in the world. Lorraine Hunt Lieberson, at Boston’s Symphony Hall in Berlioz’s Roméo et Juliette, stepping out of the huge narrating chorus to sing the a cappella recitative about the fate of the young hero, “Le jeune Roméo, plaignant sa destinée.” Again, the beauty and urgency of the line was transfixing.

There are other opera and jazz singers who regularly have had this effect on me: Joyce DiDonato, Cécile McLorin Salvant, the late Carol Sloane and Tony Bennett, a few more. And always, always, Callas.

The Polish contralto Ewa Podleś told Opera News, regarding the arguments about Callas’s various vocal registers and overall sound, “Maybe she had three voices, maybe she had three ranges, I don’t know — I am a professional singer. Nothing disturbed me, nothing! I bought everything that she offered me. Why? Because all of her voices, her registers, she used how they should be used — just to tell us something!”

Callas’s own “natural” gift didn’t come without effort. One of the pleasures of the Callas collection — aside from hearing her in multiple performances of a given role through the years — is that it provides a front-row seat to the singer’s artistic process. Here we learn that — aside from her enormous gifts — Callas’s talent was also for intellectual rigor and plain hard work.

Maria Callas with Grace Kelly, Princess Of Monaco in 1962. Photo:Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images

Callas freaks will already be familiar with the Juilliard master classes. In these three discs (included in the set) you can hear her coaching a handful of students from the 25 singers she taught that year (selected from 300 applications). Sometimes it’s a matter of going over a phrase again and again with a student, offering critiques like “don’t scoop” up to the note, but hit it cleanly, and about saving breath to sustain a long line. And always, the purpose is to show that “correct” musicality makes for a more compelling and true characterization.

Throughout these classes she offers dramaturgical insight into character. Coaching a singer in the title role of Rigoletto, she offers many pointers on characterization — even singing bits of the baritone role herself. Rigoletto, the court jester, has been keeping his daughter hidden, protected from the court and the world at large. When the courtiers kidnap her, a distraught Rigoletto has to beg them to return her.

Callas makes an important point about the young singer’s emotional delivery. “He’s crying, but angry that he’s crying,” angry that he has to flatter men whom he wants to murder. The singer, she says, has to convey both. “You should be like an animal when you sing this aria. A real animal who is trying to dominate himself” and hide his real feelings. At the end of the session she says, encouragingly, “You understand, kid? Now, you have the voice, and you can do it!”

In John Ardoin’s book of edited transcriptions, Callas: The Master Classes, she says at one point, “[Treat] ornaments in Mozart as you would those in Bellini — on the beat, well oiled, and directly stated.” Elsewhere, she gives painstaking advice not only on vocalizing but on professional practice. “There you can take a little bit of time” she tells the Rigoletto baritone about one passage. “If the conductor will permit you,” she adds, citing the difficulty of the tempo shift for the orchestra. “But try to persuade him,” to general laughter from the master class audience.

In every instance, she is courteous, encouraging, not the vinegary doyenne of playwright Terrence McNally’s fictionalized Master Class. The discs often offer selections from Callas’s own studio recordings of the roles she is teaching, such as “Non mi dir,” from Mozart’s Don Giovanni. Here is Callas in 1953, in her glory. The master classes were not recorded under studio conditions; Callas is on mic, and the students are slightly off. But the youthful bloom of the student voices comes through. Nonetheless, when Callas follows up with her own reading of a line, she has more than audio fidelity in her favor — the weight, the conception, the belief. Listening to the two voices in sequence, you’re left incredulous. God damn!

Maria Callas in 1960.Photo: STILLS/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Callas’s gracious professionalism is nowhere more evident than in the previously unreleased “Studio alternate takes and working sessions 1960-1964.” When the disc opens with the gleaming lines and ably supported high notes of “Bel regio lusinghier,” from Rossini’s Semiramide, recorded in May 1960, you might wonder, “Wait, wasn’t her voice supposed to be in decline by this point?”

Still, multiple takes show this incomparable artist working hard to get it right. After Take 90 (!) of “Sorgete, è in me dover quella pietade” (from Bellini’s Il pirata), Callas has a revealing studio exchange with her longtime producer, Walter Legge.

“Shall we have another one?”asks Callas.

Legge: “What for?”

Callas: “You mean it was good? [Yes] …. Perfect? [Yes] Harsh? [No].” She laughs, “Hmmm…. Are you sure, Walter?”

In another studio exchange, after multiple takes and consultations with the conductor, Antonio Tonini, she apologizes to the orchestra: “Excuse me, gentlemen, we’re trying to get something perfect — please forgive me.” At the end of the session she says, “Thank you, gentlemen, for your patience.” The orchestra responds with the traditional “applause” of the tapping of bows on music stands.

This is the tempestuous, impossible diva of legend? She is nothing but apologies for trying to get something “perfect.”

Contrary to legend, we are also told that Callas was the first to arrive for rehearsal and the last to leave, never asking more of her colleagues than she would ask of herself.

At the end of one especially demanding master class, Callas compliments a young soprano on the progress she has made: “Brava, kiddo! I still congratulate you for your improvement.” But only after commenting on one difficult passage, “You’ll work on that, eh?”

Perfection has a price.

Jon Garelick regularly writes about jazz for the Arts Fuse, Boston Globe, and other publications. He can be reached at garelickjon@gmail.com.