New York Film Festival: “Pictures of Ghosts” — Kleber Mendonça Filho’s Phantom Cinema

By David D’Arcy

This thoughtful documentary watches cinemas vanish from a Brazilian city.

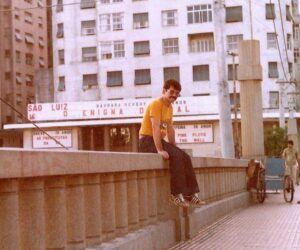

A scene from Pictures of Ghosts.

Pictures of Ghosts, Kleber Mendonça Filho’s documentary at the New York Film Festival about the disappearing (and mostly disappeared) cinemas of the northeastern Brazilian city of Recife, is a narrated tour of the spaces where the director lived and watched movies. Most of those theaters are gone, but his memories aren’t. The film is an archival adventure. Just don’t expect a happy ending.

Thoughtfully elegiac, calmly unsentimental, the film is Brazil’s nominee for the Academy Award for Best International Feature Film, a rare slot for a documentary. Even better news — it has a US distributor.

This is a personal story, which is why the director opens the film with footage — lots of it — from the apartment where he grew up, in a seaside neighborhood where identical high-rises now crowd together.

A scene from Pictures of Ghosts.

Adolescence for Mendonça Filho was dedicated to making his early films at home. Characters include his late mother (a historian of racial emancipation), camera-ready neighborhood children, gangs of feral cats who walk effortlessly through a concertina wire installed to keep them out, and a neighbor’s barking Weimaraner — warning about something — whose sudden fate on a terrace is a bellwether.

Mendonça Filho’s 2019 Western, Bacurau, mixed small-town earthiness with an odd magic realism in the Brazilian interior. In his documentary, we watch as elements usually associated with fiction, especially horror, creep into this hodgepodge of a memoir.

Pictures of Ghosts is rigorously but loosely constructed, drawing on an affection for Recife, a city known globally for its celebrations of carnival. One of the documentary’s special moments is a performance in the street of an example of the carnival dance style called frevo. The archival intermezzo is built around a choreographed fight that whirls into an entropic ensemble of movement.

This memoir isn’t a systematic history, but a collage of testimony and archaeology conveyed via a collage, a mosaic of formats. A conventional chronicle would have been a lot longer. Mendonça Filho revisits the construction of gleaming movie palaces — not too many, but strategically placed on the “dirty” river that divides Recife. Then we see the demolition or repurposing of those short-lived cinemas before there was enough of a constituency to appreciate the cultural importance of preserving the modernist structures. The buildings’ destruction inevitably meant the dispersal of audiences: cinemas were places that brought communities together; these disappearances left the downtown empty and neglected. Sound familiar?

Bear in mind that this is Brazil, where it can feel that there are more curvy modernist structures per square foot of land than in Palm Springs. Did developers and politicians and their wrecking crews presume that, with so much modernist architecture around, tearing down a few movie theaters in a “dangerous” area wouldn’t make a difference? In one surprising scene, we watch as one theater is repurposed into an evangelical church, with everything left in place, even the screen.

“When I revisited these images, I saw they might reveal the beginning of profound changes in Brazil’s relationship to religion — Catholics losing ground and Evangelicals gaining power,” Mendonça has noted. The evangelicals appealed to the same popular audience that might have gone to blockbuster movies, so, to exploit that, “they bought cinemas.”

One of the unconverted, undemolished theaters still stands in Recife. Mendonça Filho shows us crowds waiting for a screening as a poster goes up on the wall advertising Easy Rider (entitled “Sem Destino” in Portuguese, meaning “without destiny” or “without destination”).

I spoke to Kleber Mendonça Filho during the festival. (For more from the director, here’s another interview onstage at the New York Film Festival.)

Director Kleber Mendonça Filho — “the film is about time and the way time passes, and you can actually photograph time in cinema.”

The Arts Fuse: Why do you begin a film about the disappearance of cinemas in Recife with a long section set in your family’s apartment?

Kleber Mendonça Filho: After beginning to edit the film, at some point it felt predictable, almost like a catalog of old movie palaces. Then something else happened. It had to do with my emotional reaction to the film that I was making. Me and my wife decided that we were going to move. We were going to leave the family house, the apartment where I lived many years of my life. That’s when I realized that the apartment would be part of the film. Not because it’s about me. I really don’t think this film is about me. I think this film is about places, and my relationship to these places.

Because the apartment was shot from so many different angles and so many formats over the years, I really thought it was interesting to do a montage, almost like a Dziga Vertov montage of that one place, but seen from so many different angles and life situations.

The logic applied to the apartment is the same logic applied to the downtown area. You can see the living room from many different angles and you can also see the steel bridge [Boa Vista, a Recife landmark from 1876, not yet demolished] from many different angles when we move to the downtown part. It’s quite clear that Pictures of Ghosts is about time and the way time passes, and you can actually photograph time in cinema.

AF: How did you assemble the visual elements of the film?

Mendonça: It began with my own archives, my own videotapes from 33 years ago, when I was a student at university. I shot a lot of VHS footage and took still photographs of movie palaces that were closed, and also the ones that were still operational, but would close. By then the multiplex system was being promised as the new revolution for film-going. Even if I was very young at the time I think I was aware of looking at an interesting moment in history. Maybe five to seven years ago I went back to them, and I thought I might make a film about culture and film-going, and the passage of time. That’s when I began to access other archives, like television archives. Also, I posted something on Instagram, asking people and families to send me pictures from the past with cinemas in the background. I found that families hold great archives.

AF: What struck me in the film was how short the life-cycles of cinemas have become, no matter how grand. In Berlin, the massive CineStar theaters beneath the Sony Center closed after only 20 years – 2000 to 2019.

Mendonça: In 1988, there was a new, very small cinema, near where I lived, and by 1994 it was closed. It was the shortest life-span of any cinema that I have known in Recife.

AF: You also take us through the life of the elegant Veneza cinema, which opened with grandeur in 1970 (showing Airport, and Tora, Tora Tora for the military who censored films then) and closed quietly 28 years later.

A scene from Pictures of Ghosts.

Mendonça: To become something else, a shopping mall. It’s almost like a Cronenberg-ian mutation.

AF: David Cronenberg might appreciate that. Venerable cinemas (Uptown Theatre, 1920 -2003) have been demolished in Toronto, his hometown, although the preservation record for cinemas there, so far, is better than in most other cities. In Recife, are we talking about a migration of theaters with the population or abandonment?

Mendonça: I believe that a new product had to be introduced, and the new product was the shopping mall. In Recife, when they were introduced in the early ’80s, the money people found a way to drive people to the new locations. This was almost like a blitzkrieg against the downtown. The message was that the downtown was dirty and dangerous and that the shopping malls had air conditioning. This is exactly how it happened when CDs came along in the ’80s. Basically, people were told to throw out their vinyl collections, because vinyls were bad and CDs were the future. I look at all of this as a bizarre experiment in how capitalism works.

AF: Why do you think that Pictures of Ghosts was chosen as the Brazilian nominee for Best International Feature Film? Collective by Alexander Nanau (2019) was chosen by Romania, and made the final list for that year. Flee, also animated, was selected by Denmark in 2021, but it is rare for a documentary to receive that nomination.

Mendonça: The film is about cinema, and it did incredibly well in theaters in Brazil around the time that the decision was made, and it still is doing well. I was surprised, but at the same time I’m happy. I usually go where a film takes me, and Pictures of Ghosts seems to be making a lot of friends every time it screens.

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.