Concert Preview: The Boston Philharmonic Orchestra’s 45th Season Opener

By Jonathan Blumhofer

The concert, which along with the Elgar Violin Concerto also includes Rossini’s William Tell Overture and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7, promises to be a momentous occasion for the ensemble.

Violinist Guy Braunstein. Photo: Boaz Arad

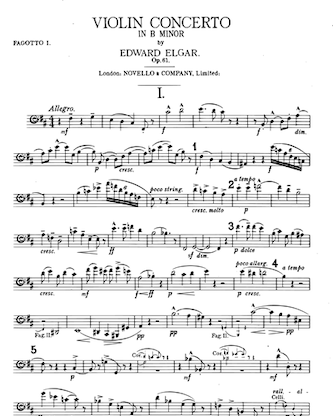

Edward Elgar wasn’t usually keen on offering personal takes on his own compositions. Yet about his Violin Concerto, Elgar was unequivocal: “I love it,” he was heard to say on multiple occasions. And that sentiment was, at least initially, echoed by the public: the score’s November 1910 premiere was a popular triumph, on par with the greatest of Elgar’s career.

Eventually, however, some of the shine wore off both the piece and its composer. As Elgar’s star waned in the years following World War 1 and into the middle of the 20th century, this long, complex work didn’t entirely disappear. But it did move to the fringes of the repertoire and achieve a certain niche status, while comparably challenging concerti like Bartók’s Second and Shostakovich’s First established themselves firmly in the canon.

The Concerto’s relative local obscurity is borne out by a look at its performance history with the Boston Symphony: the city’s flagship orchestra has only programmed Elgar’s Violin Concerto five times (the first, with Jascha Heifetz a few weeks before the composer’s death in 1934; the most recent, with Nikolai Znaider in 2010). By comparison, Shostakovich’s effort from 40 years later has been presented 11 times since 1964.

Accordingly, performances of the Elgar Concerto are often “events.” The Boston Philharmonic Orchestra and conductor Benjamin Zander are anticipating just such a thing this week, showcasing the work in their season-opening concert on Friday night at Symphony Hall. For the occasion, violinist Guy Braunstein, who last appeared in Boston in 2014, makes his BPO debut.

As far as Zander is concerned, Braunstein is the ideal soloist for the Elgar. “No one plays [the piece] like he does,” the conductor declared after Monday night’s rehearsal at Cambridge’s Holy Trinity Armenian Church. “Elgar wrote it for [Fritz] Kreisler and his playing was so flexible and soulful. Nowadays, everybody listens to Zukerman or Hilary Hahn … but they’re strict and rigid by comparison. Guy plays like Kreisler or Ivry Gitlis.… I think Elgar would be quite pleased with his interpretation.”

Braunstein’s background as an orchestral player (he was concertmaster of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra for 13 years) is one of the keys to his singular approach. “He’s so sensitive to everything the orchestra’s doing, every nuance,” Zander noted. “It’s really remarkable. And he’s also happy to follow me — rather than the other way around — which means that we can coordinate all the rubato and phrasings [between soloist and orchestra] in the piece so naturally. Of course, I have to completely understand what he wants to do, but we’re already largely on the same page.”

The concert, which also includes Rossini’s William Tell Overture and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7, promises to be a momentous occasion for the ensemble. In addition to kicking off the BPO’s 45th-anniversary season, it is being dedicated to the memory of Zander’s former wife, Rosamund Stone Zander, who died unexpectedly last month.

During the break on Monday evening, I got to chat briefly with Braunstein, who had arrived from Rome less than two hours before the rehearsal began. Below is a transcript of the main points from our conversation. (They’ve been condensed and edited for clarity.)

AF: You played this piece for Yehudi Menuhin (who recorded the Violin Concerto with Elgar conducting in 1929) when you were a teenager. How did that come about?

AF: You played this piece for Yehudi Menuhin (who recorded the Violin Concerto with Elgar conducting in 1929) when you were a teenager. How did that come about?

Guy Braunstein: Well, I’d been fascinated with this piece since I was a little kid and I learned it and studied it. And, one day, I found out that Menuhin would be coming to Israel, so I wrote a letter to his people and got a response that, on so-and-so day, I should come to his room at the King David Hotel in Tel Aviv at 4 o’clock. And I’d have exactly one hour with him. Well, I got there at 4 o’clock – and didn’t leave until 8!

AF: Given how beautiful this music is, and how well it fits the violin, not to mention how tuneful and engaging the writing is — both for listener and performer — it’s surprising that the Elgar isn’t more widely played. Why do you suppose that’s the case?

GB: Well, first of all, it’s f—ing hard. And it’s long — nearly 50 minutes. So those are two things. It’s also very challenging to put together with an orchestra since there are so many moving parts and coordinating all of them takes a lot of rehearsal time.

AF: You’re a former orchestral player…

GB (laughing): Oh … you know about my criminal past!

AF: What sort of insights or experience does that background give you when it comes to rehearsing and performing this piece?

GB: Well, it’s extremely important [in the Elgar for the soloist] to be able to play with the orchestra, not just to expect them to follow you wherever you go. You know, there are lots of orchestral players who would make wonderful soloists because they understand [how to collaborate like] this. But often, soloists just think “I’m going to do what I’m going to do and the orchestra will just follow.” But that attitude doesn’t work in this music.

AF: How did you get connected with Benjamin Zander and the Boston Philharmonic?

GB: I’ve been an admirer of his for a long time now, but from a distance. My first pianist, who I played in a duo with when I was a kid, after we played together for a few years, he left Israel to go study at NEC. And when he came back, he told me about all the classes he was taking — lessons, chamber music, all of that. But there was this guy [Zander] who had become sort of his “musical papa.” So, of course, I was intrigued and followed what he was doing from abroad. And now — finally! — we’re working together.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Guy Braunstein is a magnificent violinist – perhaps I should say artist, since he transcends the “violinist” label. As to why the Elgar violin concerto is not performed as often as other war horses, I must disagree. Conductors choose not to put it in their programs because the thing does not sell, at least not as well as the six or seven other violin works which have been performed thousands of times since their introduction to the public. Despite its difficulties, many violinists learn it and then forget about it when they find that conductors don’t need it (and conductors don’t need it because audiences don’t want it.)

Please note that the other main work on this particular program is the extremely popular seventh symphony by Beethoven.The Elgar concerto is a great piece but I think it’s too much of a good thing – too many notes. After thirty minutes of it, you want to go out for a glass of wine. Elgar was a fiddle player and he should have known better. Was he trying to compete with Brahms or Tchaikovsky? (I really appreciated this wonderful article and the interview. Thanks!)