Arts Commentary: Chile’s 9/11 — the Undying and the Undead

By Peter Keough

Two Chilean artists look at the death of democracy and the aftermath of the 1973 coup.

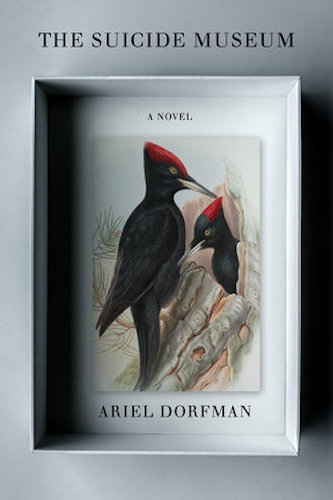

The Suicide Museum by Ariel Dorfman. Other Press, 688 pp., paperback $21.99.

El Conde directed by Pablo Larain, on Netflix.

Like the burning Twin Towers are for those in the US, the picture of jets attacking La Moneda, the Presidential Palace in Santiago, Chile, on September 11, 1972, is a recurring nightmare for Chileans. The image appears repeatedly in documentarian Patricio Guzmán‘s consummate two trilogies about Augusto Pinochet’s coup against the country’s democratically elected leader Salvador Allende. Five decades later, the spectacle looms in the background of two works issued by Chilean artists commemorating the 50th anniversary of the event, Ariel Dorfman’s novel The Suicide Museum and Pablo Larrain’s El Conde.

Like the burning Twin Towers are for those in the US, the picture of jets attacking La Moneda, the Presidential Palace in Santiago, Chile, on September 11, 1972, is a recurring nightmare for Chileans. The image appears repeatedly in documentarian Patricio Guzmán‘s consummate two trilogies about Augusto Pinochet’s coup against the country’s democratically elected leader Salvador Allende. Five decades later, the spectacle looms in the background of two works issued by Chilean artists commemorating the 50th anniversary of the event, Ariel Dorfman’s novel The Suicide Museum and Pablo Larrain’s El Conde.

After the smoke cleared after the attack, Allende lay dead along with scores of his followers. Thousands more would be murdered, tortured, imprisoned — or would simply disappear — over the following 17 years of Pinochet’s bloody reign. Others, like Guzman and Dorfman, would escape into exile, from which they would resist the tyranny through other means.

In Dorfman’s sprawling, uneven, but engaging novel, which features a fictionalized version of the author as protagonist and as a first-person narrator of wavering reliability, this flight from Chile, not to mention his failure to be at his hero Allende’s side during his last moments, fills him with a sense of guilt he cannot shake. As he (the real Dorfman, not the fictionalized one) said about writing the novel in a recent NPR interview:

Guilt — Yeah. I never made it to La Moneda. And that’s what I was really doing here. I was getting rid of my trauma in a sense, the trauma of my guilt at not having made it to a place where Allende, who was, like, sort of a substitute father for me, died there. And I wasn’t there either to save him or to help him or to witness this, right? So the novel is, in some sense, my penance for not having been there. And at the same time, it is my homage to the person who I was supposed to be there for.

Along with other reasons — some altruistic, others less so — this guilt motivates his fictional persona’s decision to take up an offer from Joseph Hortha, a mysterious Dutch billionaire and Holocaust survivor with complicated guilt issues of his own, to investigate the circumstances of Allende’s death. Was the President killed while fighting, or murdered by the invaders, or, as the Pinochet regime first reported and as most have subsequently come to believe, did he commit suicide?

So “Dorfman” returns to post-Pinochet Chile in 1990 under the guise of researching a novel he is writing. (The premise of which, about a serial killer operating in the Argentine embassy where hundreds of Chilean refugees from Pinochet’s wrath, including Dorfman, were hiding out until they could flee the country, seems more cogent than that of the novel in which it appears). There he interviews some of his surviving colleagues from that time. In the course of the questioning he discloses his own history with Allende and why he did not show up to be at his side at the end. He also goes into his efforts while an émigré to keep the resistance alive. But uncovering the truth about Allende’s death proves to be elusive.

Why should it matter if Allende committed suicide or not? Would suicide diminish in any way his accomplishments, his courage, or his legacy? Would it mitigate somehow the villainy of those who usurped him? One character argues that suicide is certainly preferable to flight. “‘I’d rather commit suicide, Ariel,” he says, “than go into exile. Because exiles and migrants…do more injury to their native lands than people who kill themselves…Suicides, at least, don’t betray their nation.’”

But, for Hortha, the issue of Allende’s suicide is more complex. At one point he explains to the novel’s narrator that finding out the truth about how he died would determine whether Allende’s fate is “tragic or epic” – “‘Tragic if he killed himself,’” he says, “‘epic if he fought to the end.’” He also notes that on two occasions Allende, by his achievements, lifted him out of despair and dissuaded him from suicide.

The bombing of La Moneda on September 11, 1973, by the Chilean Armed Forces. Photo: Netflix

Mostly, though, Hortha needs to confirm whether or not Allende committed suicide to determine if he should showcase him in his proposed museum of the title, a multi-media expo of sorts of the greatest hits in suicide — from Socrates to Hitler, from Cleopatra to Sylvia Plath. The purpose of such an exhibition would be to show the world that it, too, is on the path to self-destruction through environmental disaster if something isn’t done about it.

Surely, if Hortha wants to save the world, there must be a better way to spend the six or seven billion bucks he plans to unload on this boondoggle? Not so, claims the tycoon: “‘[W]hen we face such an existential crisis, humanity doesn’t require rational arguments, piles of scientific data, news bulletins, equations and formulas and mathematical axioms. None of that has troubled our consciousness. But a chilling story, that’s another matter.” Is there a tourist alive, he argues, who could resist a theme park filled with the narratives of those who have chosen death? Who wouldn’t scratch their head and recognize the relevance of such stories to the fate of the planet and act on this realization? “‘They’ll come in droves,’” he insists. “‘Wouldn’t you go to a museum dedicated to suicide?’”

Frankly, no. Or maybe just to visit the gift shop. Hortha’s project is urgent and laudable but weirdly amorphous and ambiguous. Kind of like Dorfman’s novel which, despite its flaws compels with its sheer honesty and dogged inventiveness.

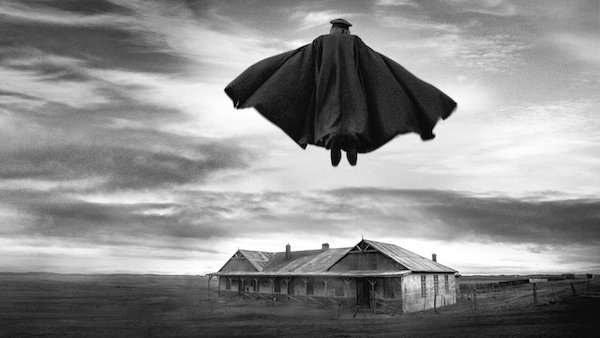

While Dorfman investigates the manner of Allende’s death, Pablo Larrain, who was born five years after the overthrow of Allende in 1976, questions whether Pinochet, who officially succumbed of heart failure in 2006 at 91, died at all. Having put his spin on such departed celebs as Princess Diana in Spencer (2021) and Jaqueline Onassis in Jackie (2016) here he takes a more lighthearted look at this darker subject. Opting for the horror genre to tell his story, he draws on that venerable and resilient figure of aristocratic parasitism and malignancy, the vampire.

A scene from El Conde. Photo: Netflix

Like most vampires, the revenant we know as Augusto Pinochet has a long history. Beginning with a voiceover narration from an initially unidentified woman with a plummy English accent, the film relates — via Ed Lachman’s lush and rancid black and white cinematography — the despot’s origins as an officer in the army of Louis XVI. It is in that service that the 20-year-old then known as Claude Pinoche (Clemente Rodríguez) discovers his taste for human blood and barely escapes getting a stake in the heart for his troubles, employing the vampire killer’s mallet in his self-defense to especially grisly effect.

Ever the opportunist, he switches sides to the sans culottes, but makes a point of licking the blade of the guillotine that fell on the neck of Marie Antoinette, later retrieving her head as a fetishistic trophy. Vowing then to dedicate his life to quashing popular uprisings, he fakes his own death and vanishes to reappear periodically throughout history as a foot soldier fighting against the revolutions in Haiti, Russia, and Algeria.

He catches his big break in Chile in 1935 as an officer in that sputtering democracy’s army. Rising in the ranks, in 1973 he overthrows the government in a coup d’état, “rescuing Chile,” in the words of the increasingly unreliable narrator, “from a Bolshevik infestation. He conquered and brought prosperity to Chile and made himself an invincible millionaire.” His triumph is capped by a scene of him personally shooting in the head a row of blindfolded prisoners who topple into a mass grave.

Good times, but they don’t last. After being evicted from the presidency, beleaguered but unpunished, he decides to elude the slow-turning wheels of justice by faking his own death again. Now he lives in rancid retirement in a bleak compound somewhere in the Chilean hinterlands surrounded by sour knickknacks from the past. He relies for sustenance on frozen human hearts gathered by his ruthless henchman Fyodor (Alfredo Castro), which are whipped up in a blender into a hemoglobin-rich frappe. Though attended by his long-suffering Lady Macbeth-like wife Lucía (Gloria Münchmeyer) he nonetheless finds the urge for fresh blood irresistible. Garbed in his cape and general’s uniform, wielding a wickedly curved knife, he flies out into the night in search of prey.

Paula Luchsinger as Carmencita in El Conde. Photo: Netflix

Disturbed that these nocturnal forays will betray his continued existence, and also desirous of his supposed millions still stashed away in secret overseas accounts, Pinochet’s children gather at his estate to find out what is going on. Meanwhile Carmencita (Paula Luchsinger), a nubile nun/accountant equipped with an exorcism kit and a wooden stake, has been sent by the Vatican to examine Pinochet’s books, expropriate what she can from his wealth for the Church, and dispatch the undead and now unwanted vampire. The intrigues of Lucía and Fyodor complicate matters still further. Though diverting, these loose ends seem more like distractions intended to delay the final acrid twist of the denouement. Like Dorfman’s novel, El Conde tends to dither.

Still, Lachman’s dazzling images, backed by an apt, arch soundtrack with music ranging from Henry Purcell’s “Cold Song” to Rosita Serrano’s 1956 hit “I Love Men,” never fail to dazzle. And, when El Conde engages history as nightmarish farce — not as epic or tragedy as Dorfman’s Hortha would have it — the film achieves the dark hilarity of Jemaine Clement and Taika Waititi’s What We Do in the Shadows (2014). Flaws notwithstanding, both The Suicide Museum and El Conde serve as valuable reminders that, unless those who commit crimes against humanity are brought to justice, the life of democracy is endangered because their evil will live on.

Peter Keough writes about film and other topics and has contributed to numerous publications. He had been the film editor of the Boston Phoenix from 1989 to its demise in 2013 and has edited three books on film, most recently For Kids of All Ages: The National Society of Film Critics on Children’s Movies (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).

Tagged: Ariel Dorfman, Augusto Pinochet, El Conde, La Moneda, Pablo Larain, Pinochet