Book Review: “Blood In The Tracks” — Bob Dylan’s Mystery Musicians

By Daniel Gewertz

Blood In the Tracks delivers a minor miracle: a host of fresh looks at the most (over)written about musician of our age.

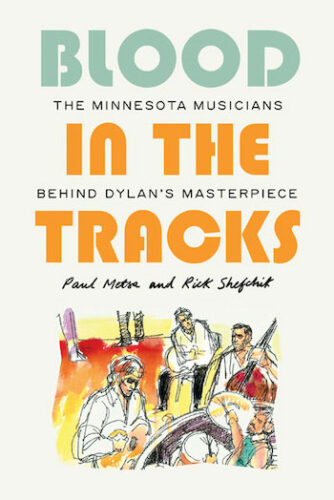

Blood In The Tracks: The Minnesota Musicians Behind Dylan’s Masterpiece by Paul Metsa and Rick Shefchik. University of Minnesota Press, 200 pages. $24.95.

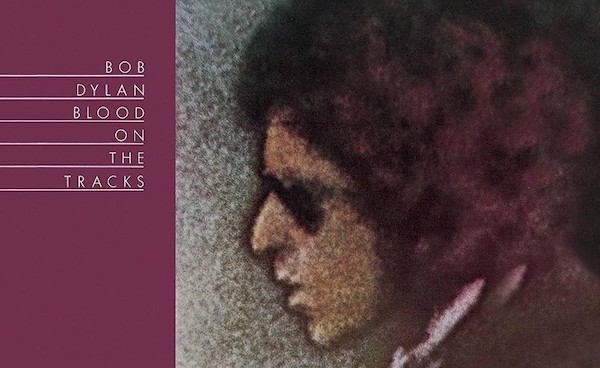

How did it come to pass that a handful of obscure Minnesota musicians won the plum-job of recording one-half of Blood On The Tracks, Bob Dylan’s career-topping 1975 album? More surprising: why did these Minnesotans remain anonymous and uncredited even after the album became one of the most celebrated discs in pop music history? This book retells the story of what has been known for a while from a fresh perspective. Co-writers Paul Metsa and Rick Shefchik zero in on the lives of the unheralded Minneapolis musicians themselves, both before and after the most fluky few days of their professional lives.

That said, the prepositional switch of the book’s title, Blood In The Tracks, seems opaque for such a no-nonsense book. Perhaps it is a reference to the musician’s bloodlines or a nod to Dylanesque ambiguity. Thankfully, the subtitle is reassuringly straightforward: The Minnesota Musicians Behind Dylan’s Masterpiece indicates that the book’s focus rests not so much on Dylan as on his “mystery musicians.” The narrative carefully follows the lives of these musical journeymen from the 1960s to the present. But Dylan completists need not fear: there’s enough about eccentric Bob here to satisfy their encyclopedic curiosities.

The overall storyline of the recording of Blood On the Tracks — both its New York City and Minneapolis sessions — has already been told in book-form some 19 years ago in A Simple Twist of Fate, published by Da Capo Press. In fact, that 2004 book’s co-writer was guitarist Kevin Odegard, one of the key figures in the new volume. Despite the overlap, this volume delivers a minor miracle: a host of fresh looks at the most (over)written about musician of our age. As a lengthy magazine article, the material here would make for a spellbinding read. As a book, though, Blood In The Tracks comes off a padded affair, even at 200 pages. And yet, if you harbor an interest in the musician as everyman — that venerable breed of honest artisan who often made a living but never a killing — the details and anecdotal tales are often captivating. In our current age of techno-hell — an era when the live music barroom is inching toward extinction — the hardworking musician may not be knocked out cold, but he’s surely on the ropes. This book tells of a better time, even though the players in question were screwed over.

1974 was a watershed period for Dylan. Despite solid reviews and great sales for his 1973 album Planet Waves, he was aware that he was treading water as a writer, or even worse — sinking fast. Songs no longer unconsciously erupted from his fertile mind with the regularity of oceanic high tides. In California, his marriage was apparently dissolving. Retreating to New York, he studied painting with artist Norman Raeben, which ultimately helped put him in a mental space to write songs in a new manner. By the summer, Dylan had penned a whole batch of highly personal songs he felt passionate about. He’d sing bunches of them to a few friends, running them all together like a slow shuffle of cards.

Yet Dylan was so protective of these emerging songs that he seemed neurotically unready to decide on how he wanted to present them in advance of his NYC recording dates in mid-September at Manhattan’s A & R studios. He told his old mentor, the legendary producer John Hammond, that he was leaning toward a solo approach. The album represented Dylan’s return to Columbia Records; A & R was formerly the famed Columbia studio in which the musician began his recording career. The present owner of the studio, producer Phil Ramone, was a last minute choice to helm the project; he took a hands-off approach, letting Dylan be Dylan. On the very day of the evening recording session, (the first day of Rosh Hashanah) Ramone ran into Eric Weissberg in the halls of A & R, where the banjoist had been recording music for commercials. Ramone asked Weissberg to play that evening with Dylan. Weissberg’s band, Deliverance, came too. So, here we have a folkie famous for “Dueling Banjos” — and a band most recently making their money by cutting jingles for radio commercials. Compounding the unlikelihood of this slapdash plan working smoothly –there was no time for the band to obtain chord charts of the songs. Once in the studio, Dylan didn’t provide any. In fact, Dylan spent the long session singing a batch of songs with few breaks, all in open D and E tunings that were little known to the band. He didn’t even inform them of the songs’ keys. A handful of tunes were committed to audiotape, but everyone — except bassist Tony Brown — was let go at the end of the night. (Only one song recorded that evening made the album: the blues “Meet Me In the Morning.”) Brown and Dylan continued as a duo during the next few evenings. Pedal steel guitarist Buddy Cage later dubbed in a few touches to the album’s spare approach.

By late September the album was considered complete, but Dylan was unsure of its commercial appeal, or its effectiveness. He wanted a Top 10 single, and didn’t hear one. Ramone kept on assuring him, in frequent phone calls, that it sounded fantastic and would be a big hit. The pre-Christmas release date was pushed to early 1975. While the authors do not define Dylan’s mental state at the time, it is easy to imagine him caught between two contrary forces: he was fearful of a mass-market homogenization of his personal songs, and yet he yearned for Top 40 popularity.

Dylan spent Christmas visiting his younger brother, David Zimmerman, at the latter’s Minnesota home, bringing along his son Jacob for the week. Obviously troubled about the upcoming album, he played an acetate test pressing for his brother. David agreed that he didn’t hear a hit single. Then David had a brainstorm: he would organize a new recording of a couple of the songs at a Minneapolis studio, Sound 80, working with a handful of musicians he knew and trusted. Dylan agreed. (His visits to his home state were so secretive that few knew he ever saw his family members. That Dylan owned a farm near Minneapolis was also little known.)

Zimmerman was supremely protective of his skittish brother, and allowed no visitors into the studio. Just how hush-hush were the recording sessions at Sound 80? They made some Pentagon secrets seem mere scuttlebutt by comparison. Consider the machinations involved with Zimmerman’s search for a certain 1930s Martin guitar, the same small model that had recently been stolen from Dylan after his NYC recording sessions. Zimmerman called a musician he knew well: Kevin Odegard. Zimmerman had produced an album of Odegard’s, a singer-songwriter who made most of his money as a brakeman for the Chicago-Northwestern Railroad. When Zimmerman refused to tell him whom the guitar was for, Odegard guessed the secret.

Co-writer Rich Shefchik. Photo: Barbara Lundgren

Then Odegard phoned Chris Weber, owner of the only quality guitar store in the city. By chance, Weber had just acquired a nearly identical model to sell on consignment. “Why do you want it?” he asked Odegard. “My friend David asked me,” Odergard said, refusing to elaborate. But once Weber guessed the David in question was Zimmerman, Odegard’s tight-lipped tone suggested the guitar could only be for brother Bob.

On the night of the first session most of the musicians entered the studio not knowing whom they were about to play with. Weber, a gifted guitarist in his own right, came to Sound 80 studios to lend Dylan the guitar. Both men played the instrument a bit and Dylan loved it. Weber asked if he could maybe watch some of the session from the sound booth and Dylan knocked him for a loop: “No man, I need you to play guitar.” It soon became clear that Dylan’s attitude was looser than the local lads might’ve suspected. On “Idiot Wind,” Weber mistakenly played an A minor 7th chord instead of the A minor Dylan had strummed. Dylan replied that he liked it better than his own choice. “Leave it in there,” he said, and from time to time in future years, Chris Weber, the Minneapolis guitar store owner, would tell musicians that he had changed a chord in a famous Bob Dylan song. Dylan, meanwhile, astounded the players by the way he quickly transposed keys without using the short-cut of a capo.

The one or two evenings of planned recording stretched to four. The last night was just a simple overdub on mandolin by 21 year-old Peter Ostroushko, but the brief session provides the book’s most charming story. Brought up in a highly musical Ukrainian immigrant family on Nicollet Island, Ostroushko began playing mandolin at three years old. Before long, he added fiddle and guitar. While the secretive Dylan sessions were proceeding, he was sick in bed, fevered with pneumonia. Tired of being in bed but still very sick, he headed off to his favorite bar to play pinball, a beloved activity. Banjoist Jim Tordoff knew to try to reach him at the bar, and he then drove the fevered Ostroushko to Sound 80 as soon as possible, with mandolin in tow. He quickly added a part to “If You See Her, Say Hello.” The next day Ostroushko woke up feeling well: the fever had finally broken. He then remembered a “wonderful, crazy fever dream” about playing mandolin on a Bob Dylan album. Later in the day he told the delightful dream to Tordoff, and had to be convinced by his friend that the event indeed happened in real life: he truly had made his recording debut playing mandolin on a Bob Dylan song!

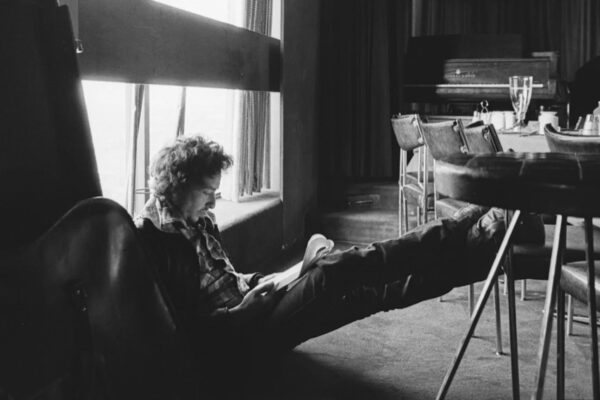

Bob Dylan in the studio circa 1974, as depicted in promo material for 2018’s The Bootleg Series Vol. 14: More Blood, More Tracks. Photo: Columbia/Barry Feinstein

The book’s best chapters center on the recording sessions, engineered by Herb Pilofer. At points, the musicians practiced a song while Dylan polished its lyrics. On “Idiot Wind,” Gregg Inhofer played piano with Dylan on organ. “We were the only ones in the studio,” said Inhofer. “I looked over and thought ‘Wow, I’m doing an overdub with Bob Dylan. Son of a bitch!” Odegard, meanwhile, likened the surreal “suspension of belief” feeling to being magically thrust inside a scene of a famous movie.

After the initial run-throughs of “Tangled Up In Blue,” Dylan asked Odegard how he felt it went. “It’s passable,” Odegard quickly replied.” Dylan, sounding annoyed, asked him what he meant. Odegard was momentarily afraid of being fired for his temerity, but he gathered up his courage and told Dylan how a few changes could transform the song from “an album cut” to a hit single: change the key from G to A, which would take the song, and Dylan’s vocal, to an edgier place, and then rev up the rhythm. Dylan agreed to try it. It worked: “Tangled Up in Blue” became the LP’s lone Top 40 song.

In terms of padding, the details we are given of the musicians’ lives became too numerous, and some of the long quoted segments weren’t edited for clarity. Still, the picture the book lovingly creates — of how it felt to be a working 20th century musician in the Midwest — is generally intriguing. Most of the players began as tots, and were never deterred from pursuing the next gig and the one after that, even if the pay was barely adequate and the traveling mind-numbing.

Drummer Bill Berg is the key player on the five songs recorded at Sound 80: a sensitive yet volcanic force. In addition to playing with an occasional name act such as Cat Stevens, he kept performing at “weddings, bar mitzvahs and supermarket openings” in Minnesota. He juggled music with a part-time career as a magazine illustrator. In the late ’70s he moved to Los Angeles and learned animation at the California Institute of the Arts, in time achieving his dream job as an animator for the Disney Studios. Eventually, he and his wife supervised a whole team of animators on The Little Mermaid, The Lion King, and others. He also kept up his drumming chops.

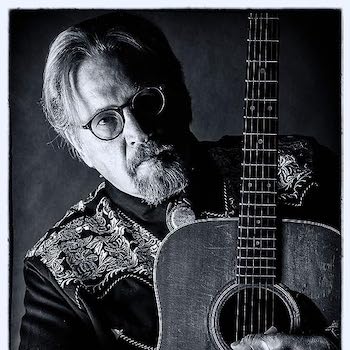

Author Paul Metsa. Photo: courtesy of the artist

The late Peter Ostroushko became famous as a regular on Garrison Keillor’s Prairie Home Companion, the nationally broadcast radio show. Pianist Gregg Inhofer’s jazz fusion band, This Oneness, toured with country-pop singer Olivia Newton-John for two years, during the time she achieved stardom. Bassist Billy Peterson eventually recorded with Steve Miller and Ben Sidran. (He also became a national champion speed-skater at age 30.) But the other Minnesotans on Blood On The Tracks never got near even the proximity of fame or fortune. And Chris Weber’s guitar shop was driven out of business after a Guitar Center opened in Minneapolis.

In the end, the reason for the musicians’ continued anonymity concerning Blood on the Tracks was no real mystery. The New York session guys got credit on the original LP because the cover for a first run was already printed. There was a promise to change the credit listing with a second pressing, but to quote a Dylan song, “nothing was delivered.” Why? In the end, it was simple: only Dylan could’ve asked Columbia to change the credits, but he evidently didn’t care. The NYC guys, even the fired ones, received gold record plaques and even some residual payments. “We did not sign W2s, we did not sign releases,” explained Inhofer. In 2018, Columbia/Sony released a six-disc box-set containing all the remaining recorded takes of Blood. Finally, and officially, the identities of the mysterious Minnesota musicians were revealed. The box-set includes none of the Minnesota outtakes, because they all had been erased: a reflection of Dylan’s fear of bootleggers.

Over the years an elitist attitude surfaced among Dylan fanatics that the Minnesota sessions were bland and the (bootlegged) New York sessions were the real deal. When I recently listened to the spare NYC versions of Blood On The Tracks I found them a revelation: Dylan’s vocal delivery has never sounded as direct, honest, and unadorned. It is as if Dylan the theatrical performer gave way to Dylan the private, soulful composer. But it is also true that the three upbeat songs recorded in Minneapolis — powered by Berg’s drums — are far more effective. “Blood on the Tracks” is the hit Dylan had been dreaming of. “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts” takes a doleful, quirky story-song and turns it into a helium-propelled cinema-like gambol, a merry-go-round of a romp, with Berg’s drums getting faster with nearly every verse. And the ruminative, bitter “Idiot Wind” is also miraculously improved. Dylan’s scathing vocals are of hurricane force here. It’s among Dylan’s finest vocal dramatics, equal to his work from his 1965 vocal peak. Some of the song’s weakest lines are turned into howlingly affecting ones because Dylan can be heard in all his vocal “raging glory.” Perhaps he knew the lines needed saving? If the NY tracks were released in 1975 the album would’ve caused a stir, and most likely have been loved by both critics and old fans. But it would not have created new Dylan fans, which the Minnesota/New York combination surely did.

In recent years, the Minnesota crew have put on Blood on the Tracks reunion shows, even adding New York banjoist Eric Weissberg. Drummer Bill Berg has traveled to some. At a recent recording session with Judy Collins a bassist admitted to Berg that he’d never recorded with drummers before and hoped it would work. “We’re going to make it work,” Berg replied. “We’re going to listen to each other.” It was a lesson learned at many a session, among them, the one nearly 50 years ago with Bob Dylan.

Daniel Gewertz has been influenced by the people he has interviewed for newspapers and radio, including jazz artists Ray Charles, Sonny Rollins, Artie Shaw, Dizzy Gillespie, Jay McShann, Gil Evans, Dave Brubeck, Keith Jarrett, Steve Swallow, J.J. Johnson and Milt Jackson; roots musicians B.B. King, Bill Monroe, Brownie McGhee, Vassar Clements, Phil Everly, Roger Miller, Carl Perkins and Bo Diddley; folkies Libba Cotton, Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, Leonard Cohen, Rambling Jack Elliot, Judy Collins, Roger McGuinn, Steve Goodman and John Prine; classic popsters Tony Bennett, Mel Torme, Eartha Kitt and Pearl Bailey; and film/theater artists Louie Malle, Edward Albee, Jeremy Irons, Glenn Close, Susan Anspach, Yul Brynner, Michael Douglas, Diahann Carroll, Jewel, Jack Klugman and John Sayles. Daniel’s first live interview, at age 16, was with Art Garfunkel in 1966.

A great album, I also enjoyed the liner notes written by that great New Yorker Pete Hamill. It’s well worth looking up. May Pete R I P.

I was amazed to discover that Hamil’s liner notes were written about the spare, duo solo version of the album, not the famous band-augmented version we all knew.