Theater Review: “Sanctuary City” — Hiding in Plain Sight

By David Greenham

In this script, dramatist Martyna Majok has created an opportunity for those who live in (or near) cities to see and hear the struggles of the underclass.

Sanctuary City by Martyna Majok. Directed by Bari Robinson. Scenic design by German Cárdenas Alaminos. Lighting design by Mary Lana Rice. Costume design by Savannah Irish. Sound design by Sam Rapaport and Nathan Speckman. Produced by the Portland Theater Festival, staged at The Hill Arts, Portland, ME, through September 3.

(L to R) Skye Figueroa, Shawn Denegre-Vaught, and Thomas Campbell in a scene from Portland Theater Festival’s production of Sanctuary City. Photo: Doroga Media

In Portland, Maine, just last week, 60 families — 190 people — were moved from the Portland Exposition Center to hotels in nearby Westbrook and Lewiston where they, as asylum seekers, will continue to wait until someone helps them find a permanent place to live. More than 1,600 asylum seekers have arrived in Portland since the first of the year. Another large group is expected to arrive in the fall.

At the beginning of this month Massachusetts Governor Maura Healy slammed the Biden administration, citing “a federal crisis of inaction” on refugees and asylum-seekers, noting that 5,000 families are currently seeking homes in the Bay State.

Many of us are alarmed, for a variety of reasons, about the numbers of refugees and asylum seekers. Polish-American playwright Martyna Mojak, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for her 2018 play Cost of Living, has specialized in crafting scripts that remind us that these are people — individuals, with their own stories that are worth hearing. Given the concerning situation in Portland, The Portland Theater Festival’s production of Mojak’s 2020 play Sanctuary City couldn’t be timelier.

It’s the winter of 2001 — months after 9/11 — in a sparse apartment in Newark, New Jersey. “B” (Shawn Denegre-Vaught) is trying to sleep. Moments later “G” (Skye Figueroa) appears on the fire escape, banging on the window. They go to high school together, and G is in need of her own kind of asylum; her stepfather is angry and violent again.

Both B and G are immigrants. G arrived with her mother seeking asylum. B is in the country illegally — “We came here legal, but didn’t’ stay here legal,” he explains. In the aftermath of “the towers” and the rise of anti-immigrant fervor, his mother is terrified of being caught and immediately expelled, leaving her son alone. She thinks “going back” may be her only option.

Through a flurry of scenes — a flash of moments — the first act flies by. It sets up a loving, caring, and respectful relationship between these two teenagers.

As the relationship deepens, so does their concern for each other. B helps G heal from the cuts and bruises afflicted by her abusive home life, while G helps B consider ways to navigate his existence after his mother leaves, so that he can finish school and hopefully find a way forward. He’s scared, because he too could be caught by the police at any time. Trying to keep up with his studies and work in order to survive might be killing him. “It’s like I’m running in my sleep,” B confesses.

G is dealing with what looks like her own hopeless future. Until her mother shares some amazing news: she’s obtained citizenship for both her and G, got a restraining order against the violent stepdad, and, while he is at work the next day, the pair are going to pack a U-Haul and move out of town.

Things get even better for G when she learns she’s been accepted to a college in Boston. Who knows what’s next? “Wherever I end up endin’ up. That’s where I’ll end up,” she says with glee.

B is supportive, but heartbroken. His mother has now left the country; losing G means he’ll be completely alone. The pair hatch an improbable plan. They’ll get married, even though they’re not a romantic couple. It is one way that B can have a future. As the act ends, G leaves on a bus for Boston with an engagement ring on her finger. B is left to dream of what doors might open up for him once he becomes a legalized citizen of the US.

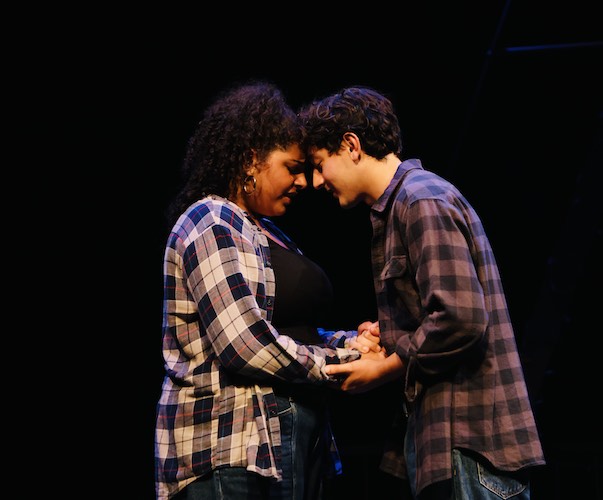

Skye Figueroa and Shawn Denegre-Vaught in a scene from Portland Theater Festival’s production of Sanctuary City. Photo: Doroga Media

As Act II opens, it’s early in 2006. G suddenly appears at the restaurant where B has been working long hours to make ends meet. They enter B’s apartment and the mood is distinctly uncomfortable. They’d barely spoken during those ensuing years, and their feelings are raw. “Nice of you to stop by on the way to a future,” B snaps. But G is unflappable; she’s about to graduate and is still willing to go along with the marriage plan.

But B’s life has changed. When his live-in boyfriend Henry (Thomas Campbell) arrives, Sanctuary City takes a provocative turn that resonates with the complicated twists and turns life takes for us all, including immigrants. Or, as Henry says, “This shit is for real.”

The Portland Theater Festival’s Sanctuary City hits with the alacrity of a lightning bolt. Figueroa’s G and Denegre-Vaught’s B strike up a dramatically compelling — and electric — relationship that director Bari Robinson maintains throughout the script’s whirlwind scenes. The second act — even though it is saddled with a more traditional kitchen-sink approach — turns out to be as interesting as the first. With the arrival of Campbell’s Henry the script digs into some of the less attractive truths about current attitudes regarding sexuality, immigrants, and good intentions.

The smart set design by German Cárdenas Alaminos includes a single window and two exposed sets of fire escape stairs. These visuals suggest the urban nature of the world outside of the apartment without undercutting the intimacy of the confrontations between the characters. Mary Lana Rice deserves accolades for her quick-change lighting design — the flash-a-rama never feels intrusive or blinding. Likewise, Savannah Irish has supplied costumes that underscore poverty and financial success in subtle ways. And the sound design by the team of Rapaport and Speckman successfully highlights the sounds of the city along with the mood of the characters.

Of course, Majok must be credited here. In this script she has created an opportunity for those who live in (or near) cities to see and hear the struggles of the underclass. There are millions of law-abiding, hard-working people in our country who are afraid of deportation, who live in fear of a single misstep. One of the play’s targets is the oh-so-tired mantra of “lift yourself up by your bootstraps.” Many of these refugees fought like hell to be here and refuse to stop fighting for justice, for a place at the table. Ever so slowly, thanks to playwrights like Mojok, their voices are being heard onstage. Or, as B proclaims toward the end of Sanctuary City, “I want to start my life — MY LIFE!”

David Greenham is an adjunct lecturer of Drama at the University of Maine at Augusta, and is the executive director of the Maine Arts Commission. He has been a theater artist and arts administrator in Maine for more than 30 years.