Book Review: “Writing for Their Lives” – How Women Established a Beachhead for Science Journalism

By Pat Reber

Writing for Their Lives shows that women led the way in interpreting the 20th century’s explosion of scientific research for the general reader.

Writing for Their Lives: America’s Pioneering Female Science Journalists by Marcel Chotkowski LaFollette. The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England, 253 pages, $26.95.

Marcel Chotkowski LaFollette, a historian who has taught at MIT, Johns Hopkins, and George Washington University, found herself recovering from surgery during the pandemic. Engaged as a research associate at Smithsonian Institution Archives, she contributed to the archive’s blog, “The Bigger Picture,” sharing what she was discovering about the early history of science journalism.

Marcel Chotkowski LaFollette, a historian who has taught at MIT, Johns Hopkins, and George Washington University, found herself recovering from surgery during the pandemic. Engaged as a research associate at Smithsonian Institution Archives, she contributed to the archive’s blog, “The Bigger Picture,” sharing what she was discovering about the early history of science journalism.

In fact, she found it was women who led the way to interpret for the general reader the 20th century’s explosion of scientific research. LaFollette’s blog contributions led to publication of this book.

Eight women are the main thread of Writing for Their Lives: America’s Pioneering Female Science Journalists, and they likely never would have found their way to a little known news agency — the Science Service — had they not benefited from several factors.

First, they were mostly the daughters of economic privilege who were able to attend college and were allowed [emphasis is writer’s] to study biology, chemistry, physics, and astronomy — in itself a breakthrough for women early last century. Second, as women scientists they were often shut out of the labs and professorships of the burgeoning male-dominated scientific research establishment but found a profession writing about their expertise. And third, they found a champion in a man — chemist Edwin Emery Slosson — who had actively supported women’s suffrage with speeches and writings, had a bent for the literary, and was an ardent supporter of popularizing scientific developments for the general public.

In 1921, a year after the 19th Amendment was ratified, publisher E.W. Scripps and biologist William Emerson Ritter founded the nonprofit Science Service news agency and went looking for “someone who advocated public outreach and who shared their conviction that democracy’s survival depended on a citizenry conversant with the latest science and technology.”

They found Slosson and named him head of the nonprofit Science Service agency with the mission of launching and staffing it. And while he did not set out to hire mainly women, his announcements seeking writers urged both men and women scientists to submit news stories and apply for jobs. The best results came from women applicants.

“Within a year, in addition to including articles about the accomplishments of female scientists, he was purchasing manuscripts from science-trained women and syndicating a column by a female astronomer,” LaFollette writes. “What counted most was whether one could write well and meet a deadline.”

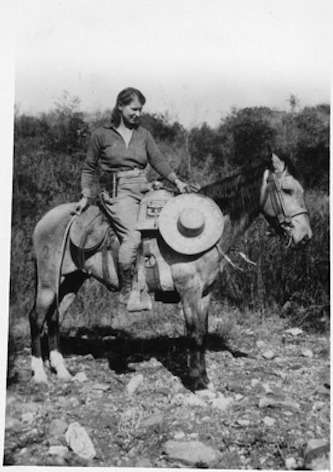

Journalist Emma Reh. Photo: Smithsonian Archives

In the 1920s, there were few newspapers with reporters exclusively assigned to a science beat. The monthly magazine Popular Science had been around since 1872, but average newspaper readers were not likely to subscribe. What Science Service offered to newspapers hungry for more science news was short, often 500-word stories on breaking science news as well as colorful features.

Of the eight writers LaFollette focuses on, three are perhaps best known — medical writer Jane Stafford, archeology expert Emma Reh, and chemist Helen Miles Davis. Most of the eight encountered the sort of obstacles women faced — and still face — in terms of access to press conferences, embargoed scientific journal articles, and professional gatherings at places that did not admit women. And they were paid less than their male colleagues.

But LaFollette’s stated purpose is not to focus on the obstacles, but rather to highlight the efforts of the little-known remarkable women who led the way and the agency that opened the door for them. Part of their obscurity AND their success must be attributed to the fact that their stories were, for the most part, un-bylined, so newspaper clients were not aware of the gender of the writer. (The bias against women in science has extended to science fiction writers. When fans of James Tiptree, Jr., a popular SciFi writer of the ’60s-’80s, found out it was Alice Sheldon wielding the pen, they stopped buying.)

The Smithsonian Archives has detailed records of Science Service history, including notes by and among staffers and with sources — and pay records!! LaFollette also found obituaries, news stories, books about women in journalism, and other documents to flesh out the biographies of her subjects.

At times, the background information LaFollette supplies about her subjects is overwhelming. There are detailed genealogies of parents, grandparents, and siblings along with information about their education, professions, and travels. One of the major challenges for a journalist is deciding what to leave out: the Science Service writers had to learn that hard lesson. But LaFollette is not a journalist. She is a historian intent on sharing her research, and Writing for Their Lives offers lively portraits of her subjects and provides solid source material for future women journalists and science writers. Here are just three of the women profiled in the book.

Journalist Jane Stafford. Photo: Smithsonian Archives

Jane Stafford was the first full-time medical journalist at Science Service (from 1928 to 1956). At Smith College, she majored in chemistry, bacteriology, and physics, afterward working as a hospital lab technician in Chicago and on the editorial staff of a health magazine published by the American Medical Association (AMA). One of her contributions to medical journalism was battling with scientists and physicians over covering professional gatherings where they presented their papers. Stafford was tireless in covering the meetings in person, making notes and filing fast, accurate stories through Science Service. When the scientists and physicians — who had beforehand refused her embargoed access — objected to the physical presence of journalists like Stafford, she stood her ground. She insisted that oral presentations amounted to the release of the papers. Through her connections at the AMA, Stafford paved the way for the current practice in science journalism of giving qualified reporters advance access to embargoed material. She became a leader in the journalism profession, helping to found the National Association of Science Writers and serving as president of the Women’s National Press Club. (Women were excluded from the National Press Club until 1971.)

Emma Reh, a chemistry major at George Washington University, joined Science Service in 1924. She struggled under the bonds of marriage, particularly having to relocate in order to follow her husband’s job. “It’s awful to be a woman and married because you really cannot have any plans of your own,” she wrote to her then-boss, Watson Davis. She launched a freelance career, driving cross country from Washington DC to Mexico where she planned to get a divorce. Along the way, she filed stories and photographs to Science Service. She stayed in Mexico for most of a decade, honing her skills in covering archeology. One outing entailed three days on horseback to a dig in Tlaxcala. By cultivating sources and being a personal presence at various digs, she forged invaluable connections. For example, she was the sole authorized source of trusted news on the pre-Columbian archeological site Monte Alban.

Helen Miles Davis, chemist, covered the 1952 nuclear bomb test at Yucca Flat, Nevada — the first time the military allowed live television and radio coverage of a test. Davis, ever the scientist, provided expert and easy to understand technical descriptions of the chemistry and physics at work in the bomb. But she also drew on her literary skills in her article “We’ll Grope in the Dark.” Here is the story’s lead: “Light 10 times in brilliance the glory of the sun may be your first warning of attack by an atomic bomb. If so, that may be the last vision you will ever have. You may be left groping in the darkness to face the bitter day when nuclear energy is turned against us.” She noted that the test explosions were “peculiarly man’s work [with] only a few feminine eyes” among the press and observers.

The Science Service agency has survived to this day, carrying on in its current identity as the Society for Science, publishing Science News (“Independent Journalism Since 1921″) and Science News Express. It sponsors scholarships and science competitions, continuing its dedication to public outreach.

The nearly 60 women science writers mentioned in Writing for Their Lives — and listed in an appendix — are testament to women’s pioneering contribution to science journalism. Other books by LaFollette include Science on the Air and Science on American Television.

Pat Reber, 76, a retired journalist living in Maryland, has worked as a reporter and editor in New York, Washington, DC, Germany, Kenya, and South Africa. While serving as deputy bureau chief in Washington for Deutsche Presse-Agentur (dpa) during the Bush and Obama years, her reporting beat was climate change and she covered the UN climate talks in Durban (2011) and Paris (2015). She last wrote a review for the Arts Fuse on Truth and Repair: How Trauma Survivors Envision Justice by Judith L. Herman.