Arts Remembrance: Appreciating Robbie Robertson

By Jason M. Rubin

Robbie Robertson was born and raised in Canada, but he seemed to understand the American myth better than most of his southern neighbors did.

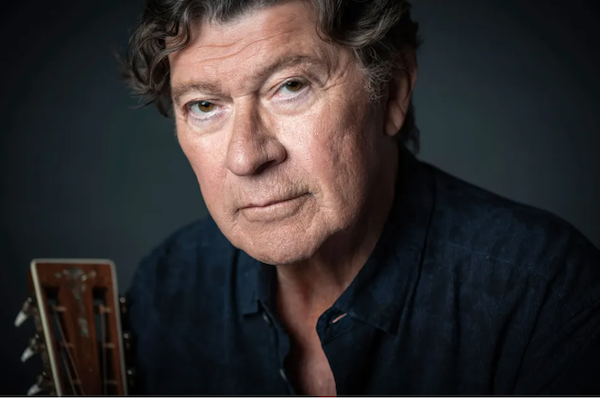

The late Robbie Robertson. Photo: Don Dixon

In the end, one forgets that Robbie Robertson was born and bred in Canada. This creator of a rootsy but literate Americana-based rock music in the midst of the psychedelic Woodstock era — who deftly chronicled the end of the Civil War from a Confederate family’s point of view, so rich in emotional authenticity that one almost forgets one’s allegiance in that holocaust — seemed to understand the American myth better than most of his southern neighbors did. His death on August 9 at the age of 80 put an enormously influential figure in the rearview mirror, even as his music remains firmly in the headlights on the long, twisting road of American popular music.

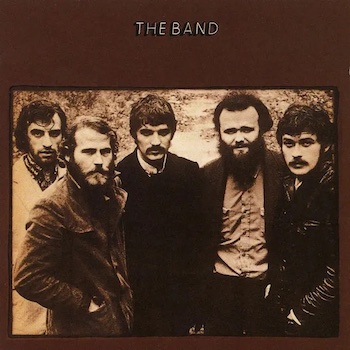

The foundations of his career are well known: backing Ronnie Hawkins, a Southerner who was more popular in Canada than in his home country; Bob Dylan handpicking Robertson and the rest of Hawkins’s band for his electric “Judas” tour of England; the band escaping to the more bucolic confines of a pink house in New York’s West Saugerties and emerging as The Band with an album, Music From Big Pink, that made Eric Clapton want to spill Cream and join the group. That album and its eponymous follow-up turned the late ’60s rock scene on its navel-gazing head, resulting in a flood of songs — including “The Weight,” “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” and “Up On Cripple Creek” — that were as eclectic as they were enduring. A late-career dip led to the exit of all rock exits, the 1976 star-studded Thanksgiving farewell captured in The Last Waltz album and film.

Of course, Robertson wasn’t alone in effecting this quiet revolution: The Band was blessed with five great musicians (including Garth Hudson, at 86 the only Band member surviving), three stellar singers (Richard Manuel, Levon Helm, and Rick Danko), and multiple writers. Robertson soon dominated the songwriting, though, which led to accusations from Helm that the guitarist was hogging the composer credits and, by extension, the royalties. What is unassailable is that established artists from the Beatles to the Grateful Dead to Elton John were soon writing songs and albums in that Americana style and crediting The Band with the inspiration.

My own take on the controversy is that if Robertson didn’t compose all those great Band songs by himself, why is he the only one to have sustained a solo career with an ongoing flow of high-quality tunes? Danko produced an album’s worth of good to very good songs right after The Band broke up, and that was basically it. None of Helm’s solo albums (some of which are exceptional) has even a single song credited to him. Manuel and Hudson: next to nothing.

Robertson, on the other hand, released six solo albums (most are excellent), wrote post-Band songs that earned significant radio play (and modest chart success), and as producer and/or composer contributed to numerous film soundtracks. Yes, the other members of The Band were great musicians and no doubt made important contributions to their music. But that doesn’t necessarily mean they co-wrote the songs. Pete Townshend certainly didn’t write parts for John Entwistle and Keith Moon, but his songs for The Who are credited to him alone. A look at Robertson’s solo career supports the idea that he was indeed the group’s primary songwriter.

His first recording on his own was an affecting track called “Between Trains” that appears on the soundtrack to the 1983 film The King of Comedy. While his strained crooning is suited to the melancholy vibe of the song — “If I’m too young to learn/Or too old to change/I guess I’ll always be/Between trains” — it is clear he lacked the vocal chops of Danko, Helm, and Manuel. One would not be blamed for thinking that unless he enlisted a true vocalist, Robertson would not have much of a solo career.

Just four years later, though, Robertson proved the doubters wrong. Robbie Robertson introduced a low, growly, speech-based vocal style that added considerable intrigue to cuts like “Somewhere Down the Crazy River,” which became a surprise MTV hit. The album overall made the Top 40 and “Showdown at Big Sky” was a Top 5 single. Co-produced by Robertson and Daniel Lanois, the album featured assists from Lanois clients Peter Gabriel and U2, but the songs were all Robertson’s and he was the primary vocalist. Rod Stewart later covered “Broken Arrow,” while “Fallen Angel” was Robertson’s tribute to Manuel, who had died by suicide the year before.

It was another four years before Robertson released his follow-up, a concept album called Storyville, about the New Orleans neighborhood that birthed jazz. Though it rose no higher than 69 on the Billboard chart, I believe it is the equal of Robertson’s first album. Members of the Meters, the Neville Brothers, and other New Orleans-based musicians lend energy, though it remains an early ’90s production, so the music itself does not feature the authentic sounds of the area that serves as the album’s inspiration. Still, Storyville is a richly textured and well-written album, and “What About Now” was a Top 20 hit.

Robertson’s third solo album was actually the soundtrack to a television documentary called The Native Americans, and it might be my favorite of his. Half-Jewish and half-Cayuga and Mohawk, Robertson focused on the latter part of his heritage and offered an intriguing blend of chants and songs written and performed by Native American artists, and original songs that fuse Robertson’s standard songcraft and guitar skills with topics and elements relevant to the subject matter. “Ghost Dancer” and “Skinwalker” are particularly intense songs, while “It Is a Good Day to Die” pays homage to the resistance of native tribes to the white man’s murderous westward expansion. “Golden Feather” is kind of a companion to “Broken Arrow” from his first album, using indigenous customs and artifacts to express loyalty and love.

After a five-year break, Robertson resumed his solo career and remained steeped in his Native American culture. Contact from the Underworld of Redboy, released in 1998, was another fusion, this time incorporating entirely new elements to his sound, such as trip hop and electronica. Though it barely made the Top 200, it features a fresh slew of compelling songs, though his take on the Native American experience now is clearly pessimistic. “The Sound Is Fading” and “The Code of Handsome Lake” are unflinching in their testimony of what has been lost, though “Unbound” and “In the Blood” show he still has some fight in him. Of particular interest is “Sacrifice,” a tape recording, set to music, of American Indian Movement activist Leonard Peltier — controversially found guilty of killing two FBI agents in 1975 — detailing the illegitimacy of his conviction. With this track, Robertson was following in the footsteps of his former boss, Bob Dylan, whose 1975 song “Hurricane” sought to free boxer Rubin Carter (both Carter and Peltier were tried by all-white juries). Peltier remains in jail.

After a five-year break, Robertson resumed his solo career and remained steeped in his Native American culture. Contact from the Underworld of Redboy, released in 1998, was another fusion, this time incorporating entirely new elements to his sound, such as trip hop and electronica. Though it barely made the Top 200, it features a fresh slew of compelling songs, though his take on the Native American experience now is clearly pessimistic. “The Sound Is Fading” and “The Code of Handsome Lake” are unflinching in their testimony of what has been lost, though “Unbound” and “In the Blood” show he still has some fight in him. Of particular interest is “Sacrifice,” a tape recording, set to music, of American Indian Movement activist Leonard Peltier — controversially found guilty of killing two FBI agents in 1975 — detailing the illegitimacy of his conviction. With this track, Robertson was following in the footsteps of his former boss, Bob Dylan, whose 1975 song “Hurricane” sought to free boxer Rubin Carter (both Carter and Peltier were tried by all-white juries). Peltier remains in jail.

Robertson’s last two albums, How to Be Clairvoyant (2011) and Sinematic (2019), really don’t do much for me. Both feature the same tepid tempos, very few guitar solos, rhythm beds that lack dynamism and differentiation, and his still-husky vocal delivery. Nonetheless, I continued to hold out hope that he would one day tour. My hope now is that, as fans dig out their copies of Band albums like Music From Big Pink, Cahoots, Rock of Ages, and The Last Waltz and soak in the musical riches ingrained in those grooves, they will also investigate and invest in Robertson’s solo records, especially the first three. They offer powerful ammunition for any argument you might find yourself in as to who really wrote all those great songs for The Band.

In the end, though, it makes no difference. The weight of history is on his side and though life is a carnival, he has now been released.

Jason M. Rubin has been a professional writer for nearly 40 years, more than half of those as senior creative lead at Libretto Inc., a Boston-based strategic communications agency, where he has won awards for his copywriting. He has written for Arts Fuse since 2012. Jason’s first novel, The Grave & The Gay, based on a 17th-century English folk ballad, was published in September 2012. Ancient Tales Newly Told, released in March 2019, includes an updated version of his first novel along with a new work of historical fiction, King of Kings, about King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. His latest book, Villainy Ever After (2022), is a collection of classic fairy tales told from the point of view of the villains. Jason is a member of the New England Indie Authors Collective and holds a BA in Journalism from the University of Massachusetts Amherst. jasonmrubin.com.