Dance Review: “Hip Hop Across the Pillow” — A Spectacular Experience

By Charlies Giuliano

Now 50 years old, a venerable landmark, in what ways does hip-hop stay put or embrace evolution and change?

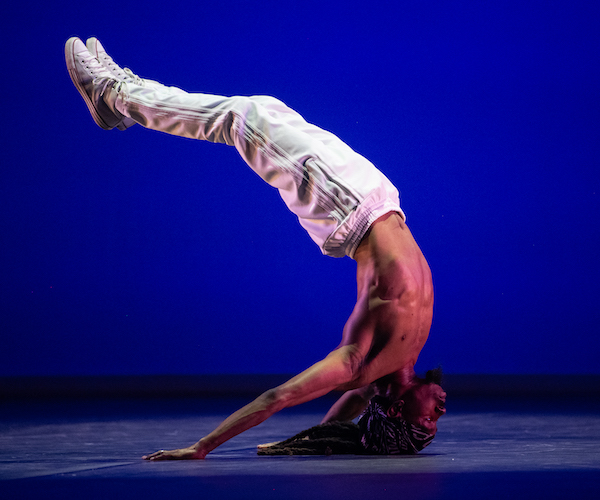

Joshua Culbreath in Nuttin’ but a Word, with Rennie Harris Puremovement American Street Dance Theater, at the 2023 Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival. Photo: Cherylynn Tsushima

Jacob’s Pillow is committed to celebrating all forms of dance. On the occasion of hip-hop’s 50th anniversary, the festival presented Hip Hop Across the Pillow.

The form evolved in the Bronx through a fusion of African and Puerto Rican dance forms in clubs and on the street. From the beginning, it featured improvisation and acrobatic athleticism. Constantly evolving and responding to aesthetic, social, and political developments, hip-hop has developed a recognizable vocabulary as well as a growing number of movements and traditions.

Perhaps you have seen groups performing in front of the Metropolitan Museum of Art or in the subway at 42nd street. Often the dancers attempt to outdo each other; the art form derives from the cutting contests and jam sessions that have pervaded Black culture since the birth of jazz and blues in the ’20s. Think of images of jitterbug dancing during the swing era at the Savoy Ballroom. In succeeding decades these indigenous dances have taken on different forms and terms.

Hip-hop combines the notions of “hip,” to be knowledgeable or savvy, and “hop,” which designates movement. While it derives from the experiences of people of color, the style evolved from the Bronx to span the United States and has expanded into a global art form.

When Black art forms become mainstream and commercialized, “the young, gifted and black,” as Nina Simone put it, tend to reinvent themselves. Now 50, a venerable landmark, in what ways does hip-hop stay put or embrace evolution and change? As we heard from the stage “God is change.” There are possibilities yet to be explored.

One of hip-hop’s masters, Rennie Harris, brought his Puremovement American Street Dance Theatre to be part of the celebration. He has been a guest at Pillow many times over 25 years and is regarded as a spokesperson and elder of hip-hop; his Nuttin’ But a Word (2016), which comprised the second half of the program, surveys the past, present, and future.

The feature-length dance in sequences was interspersed with giant video head-shot projections with Harris’s brief and informative comments. He stated that the three laws of hip-hop are “individuality, creativity, and innovation.” The transition from the street and clubs to proscenium is valid as long as there is a commitment to “community” dance and resistance to outside influences. He prefers the term “community” to “street.” The vocabulary of movement includes: Lockin, Poppin, Breakin, Rockin, and b-Boying.

Two world premieres at the Pillow drew on hip-hop to create dramatic narratives. Harris doesn’t see these as collections of “skits” but as wordless stories that reflect the afflictions of daily life for people of color. In one poignant segment, an anguished man tends to a shooting victim of a gang war or the police. The pain was heart wrenching and palpable.

Kwikstep and Rokafella in Thief of Hearts at the 2023 Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival. Photo: Jamie Kraus

Choreographed and performed by Kwikstep and Rokafella, “Thief of Hearts” was a Pillow commission. It is set to a music mix by DJ KS360, with sampling from Ian Friday’s Carib Leap, James Brown’s Give It Up, Turn It Loose, Crate Bug (Bob James)’s Take Me to Mardi Gras, and Awesome Foursome’s Funky Soul Mokasso.

Inspired by Mission Impossible, the narrative presents two masked cat burglars deftly navigating the laser alarm system of a museum. The prize is a colossal light-emitting gem set on a pedestal. There is competition and engagement between the members of the pair. With agile and spectacular moves they spar in the dark. During one segment, the dancers wear light headsets that glare out at the audience. When one robber grabs the jewel, the other snatches it away. At one point, the dancers remove their masks to reveal a thick-set male and female opponent. During their ritualized competition they both execute head spins. He returns to that move at the end and seemingly turns forever as the audience gasps in awed appreciation.

Ladies of Hip-Hop in d. Sabela grimes’s Parable of PassAge at the 2023 Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival. Photo by Jamie Kraus

The second premiere featured The Ladies of Hip-Hop — Jai’Quinn Coleman, Reyna Núñez, Imani Arrington, and Iman Brooks — in d. Sabela grimes’s Parable of PassAge, a transmedia assemblage of poetry, film, music, and improvisational movement. This is an ambitious piece choreographed by d. Sabela grimes that includes spectacular video and sound projections by grimes and Meena Murugesan. The costumes were designed by grimes and Kia McCormick. The inspiration for the live performance is the writings of Octavia Butler.

Four women of varying body types initially appear in pants and smocks on which are large images of Benin sculptures. The dancers circle and interact with the projections, which are accompanied by snatches of text and spoken word. A costume change follows and they reappear with collars from which are suspended colorful thick coils. The visuals reminded me of costumes by Nick Cave. Beyond their spectacular first impressions, however, the costumes were awkward to negotiate and impeded movement. The kaleidoscopic morphing of projected images of African beauty in the background were astonishing, but the choreography was less so.

Rennie Harris Puremovement American Street Dance Theater performing Nuttin’ But a Word at the 2023 Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival. Photo by Jamie Kraus

If the accomplishments in the first part of the program were uneven, the second half, featuring Harris’s Nuttin’ But a Word (2016), brought it on home. The large and varied company of men and women in Puremovement American Street Dance Theater demonstrated every aspect of the hip-hop genre, from its origins to the present day.

The unifying element was a huge, pulsating beat that hit you in the guts. There were shifts in the tempo to which the dancers responded — sometimes via a freeze frame that included robotic strobe moves. The dancers were able to move in certain ways — as they isolated parts of their bodies — that appeared to be physically impossible.

All the possible configurations of solo and ensemble dance were explored. Individuals, often to the roar of the audience, delivered their signature moves. The Pillow rocked as audience members howled and clapped along, particularly at the finale, which spotlit several bare-chested men in dreads. Wearing white pants, they executed impossible moves with deft precision. The response was numerous curtain calls — it was a fitting end to a spectacular experience.

Charles Giuliano has just published Annisquam: Pip and Me Coming of Age.