Arts Commentary: SAG-AFTRA On Strike — Not Just About Jobs, But the Soul of American Culture

By Steve Provizer

The battleground is where technology meets art meets finances.

SAG-AFTRA and Writers Guild of America members marching in unison, June 2023. Photo: Wiki Commons

As a member of the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA), I voted, along with 98 percent of its members, to empower the negotiating committee to strike. Negotiations had begun on June 7 and a strike was called on July 14. Reports of how far apart the negotiations are between SAG and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) portend a long strike. The Writers Guild is also on strike against the AMPTP, but even two labor actions will probably will not exert sufficient pressure to force serious concessions from the AMPTP anytime soon.

The battleground is where technology meets art meets finances. We’ve seen its like before: Radio put live music on its heels in the ’30s, then television arrived to threaten the radio and film industries in the ’50s. Over the last 20 years, streaming has wreaked serious economic damage on the music industry. Likewise, the enormous growth of broadband streaming has ravaged the financial landscape of film/video. But the arrival of Artificial Intelligence (AI) dwarfs what preceded it. This game-changing upgrade in technology threatens the livelihoods of writers, actors, painters, musicians, and composers working in every medium. It has understandably set off alarm bells in all the “creative” trades. Witness the recent litigation by authors.

With the exception of a small group of stars, the world of entertainment is the poster child for the steadily growing salary gap between the have-all and the have-none. The yawning chasm between CEOs and their average workers is gargantuan. I found wildly divergent reports about what studio heads bring home, but on May 2, Senator Bernie Sanders tweeted: “Last year, 8 Hollywood CEOs made nearly $800 million, yet pay for TV writers has fallen by 23 percent over the last 10 years.” Bob Iger, the mogul who runs the Walt Disney Corp., has been haunting talk shows, concerned about the unrealistic expectations of the SAG negotiators. He is on track to make $27 million or $31 million, depending on whom you believe.

Pity the poor moguls. Walt Disney’s Bob Iger signed a contract extension with the company that raises his annual target pay from $27 million to $31 million. Photo: Disney/ABC Television Group

It’s not easy to determine how much an average SAG member earns per year. There are 160,000 SAG members. (Despite what the New York Times and Boston Globe claim, it is a national union — not a “Hollywood” union for “Hollywood” actors.) One site reports the average per-year earnings of a SAG-AFTRA member is approximately $40,000, which is 32 percent below the national average. Another, and I think more accurate, way to gauge the pay scale would be this: To qualify for insurance through SAG-AFTRA, a member has to earn $25,950 in covered earnings within a one-year span or work 100 days. I can’t find current statistics on coverage, but in 2014, the Los Angeles Times reported that, “according to data from SAG-AFTRA … only about 15% of members qualify for health insurance through the union.” So, as of 2014, 70 percent of SAG/AFTRA members earned less than $16,000. The best year I’ve ever had is $12,000. Of course, that may be because I’m in Boston and the real money is to be made in L.A. or N.Y.C. Atlanta has a lot of production, but it’s a “right to work” state (Why have we let anti-unionists dictate that label?) The reality is that the entertainment Industry, in the form of the AMPTP, can’t gainsay the depressing numbers. No matter how you measure it, except for those at the very top, actors don’t make much money.

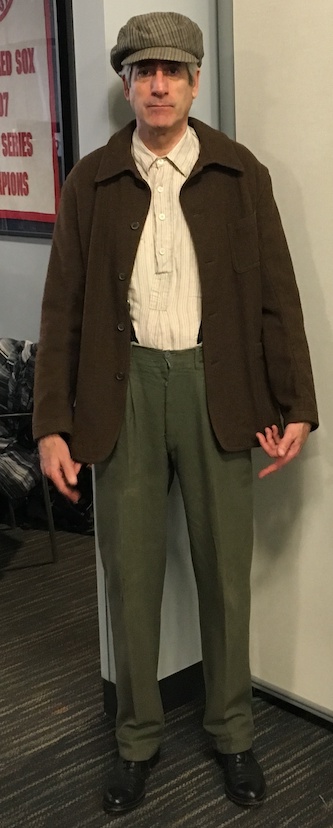

Now, let’s look at the technological issues. The SAG-AMPTP negotiations could come up with no middle ground on AI. There is almost no audio or visual aspect of a film that could not be affected by the application of AI. It can write scripts, duplicate the voice of dead actors, alter the appearance of people and places. Then, there’s the pernicious fallout of “scanning.” This is the process of taking a film image of an actor and storing it as a digital file so that it can be used as often as desired and without the individual’s permission. I was solicited to do background work on a film, but had to agree to be “scanned” in order to get the job. I didn’t like the sound of it and declined.

SAG’s lead negotiator Duncan Crabtree-Ireland has argued, “They proposed that our background performers should be able to be scanned, get paid for one day’s pay, and their company should own that scan, their image, their likeness, and be able to use it for the rest of eternity on any project they want with no consent and no compensation.”

The idea that a production company owns the right to my image in perpetuity and can use it without my consent is odious to me. I’m not interested in, for example, being a part of the next Sound of Freedom –a QAnon-infested production.

SAG is OK with “editing-type functions” that can be done without AI tools and wants that agreed to. The studios say no.

Steve Provizer dressed for a film set in the 1920s. What would producers like? To be able to scan this image and then have the power, in perpetuity, to use it in any way they wished.

The AMPTP is willing to grant principal performers the right to withhold consent for their image to be used in another film, but most actors don’t have the financial cushion to make that choice. “If you’re an actor,” Crabtree-Ireland says, “you’re desperate to get into a movie, and the AMPTP says to you, ‘OK, we’ll cast you in this movie, but only if you agree that we can do a digital scan, a digital replica of you and use it in any future project that we ever create.’ What is someone supposed to do with that?”

In one sense, the industry has been setting itself up for the arrival of AI for a long time. Of course, film itself is an illusion — our brain creates continuity out of a lot of still pictures quickly flying by. In early days, double exposures and “composite” shots were used to give the impression that actors were outside the studio. This technology could be lightly applied; for example, to make us believe Humphrey Bogart and Ida Lupino were in a roadster on the lam from the cops. Green screen technology, already explored in the ’30s, was hyperpowered by computers and has now became ubiquitous. At this point, there is very little computer-generated imagery (CGI) can’t do. CGI is expensive now, but it won’t be in the future.

If we posit that, in the past, there was a balance between the box office take on blockbusters and middle-sized or small films, then there is no question that it is becoming more and more lopsided. The megahits are taking home more of the gravy. The L.A. Times reports: The top 10 movies accounted for 55 percent of the domestic box office last year, compared with the average of 36 percent from 2015 to 2019. Affordable cameras and editing equipment have led to a boom in very low-budget productions, but these are largely amateur or film school projects, using unpaid actors. They’re almost never under union contracts.

What is being squeezed out is mid-sized production projects, budgeted between $5-50 million. These are the films/programs in which the vast majority of SAG people find meaningful work, as principals, day players, or background. These are also the kinds of entertainment/art that people who aren’t interested in the Marvel universe would like to be able to see.

The “Big Five” major companies are international, publicly traded corporations: Fox; Columbia Pictures, owned by Sony Group Corporation; Universal, owned by Comcast (via NBCUniversal); Paramount, owned by Paramount Global: Warner Bros., owned by Warner Bros. Discovery; Lionsgate Films –MGM is owned by Amazon; DreamWorks is owned by Viacom and distributed by Universal. To fertilize the bottom line — i.e., keep shareholders happy — these production houses have been increasingly reliant on blockbuster franchises that utilize alternative “universes” created by CGI and AI.

How will audiences respond to higher and higher levels of AI-generated “content”? No one knows. Part of me thinks our standards of critical/aesthetic evaluation — what we will accept at the right price — will degenerate to the point that consumers will be content to accept just about whatever is fed them. Who cares if a human being created it or not? In my cynical moments I figure that we get the entertainment that we deserve: “You don’t care? Fine.” My better self believes that SAG-AFTRA and the Writers Guild are not only negotiating for peoples’ livelihoods, but for the soul of the culture. And that that is a battle well worth waging. I don’t want to read a book put together Frankenstein-like, even if the body parts are snitched from Mark Twain and Emily Bronte. I don’t want to hear AI music, even if the notes are cribbed from Mahler and Marian McPartland. And, as far as movies go, I stopped reading comic books years ago.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Offering actors a day’s pay for the rights to reproduce their image in AI and use it in perpetuity in any context is just demonic.

I keep reading the figure that only 2% of SAG-AFTRA members are making a living as actors.

I totally agree with Steve. Here’s hoping the strike comes to an end before too long in a fair way for actors.

Great overview. Though AI purports to be an influential technique for further artistic advances, the humanistic downside can’t be disregarded. Stick it to those callous CEO cads! At the crossroads – the crucible of collusion where money & self-identity changes everything. Life in perpetuity? Give me a break.

I do some modeling for a clothing retailer. It’s an hourly gig. While working one day at their HQ, they asked if they could scan me for their sizing software used in stores. I declined. It would have been used in perpetuity and I’d have received compensation for just the few minutes it took to scan.