Film Commentary: “How I Learned to Start Worrying and Fear the Bot”

Complied by Ezra Haber Glenn

Long before the current writers’ strike, Hollywood was sounding the alarm about the dangers of AI.

A scene from a stage production of Karel Čapek’s R.U.R. Photo: Wiki Common

For as long as we’ve had work — which is to say, ever since we left the Garden of Eden — our society’s boldest prophets and inventors (and a few profit-seeking investors) have sought new ways to replace human labor with the effortless ease of technology. But while each new development may lead us closer to a brave new “labor-free” world, not everyone has welcomed these changes. Most notably, workers who have found themselves and their livelihoods in the headlights of automation’s onrush have resisted with their voices, their sabots, and their very lives — but such resistance has often been dismissed as little more than self-serving Luddism, ignored by others in the name of progress and the greater good.

And now, after replacing everyone from farmers and cobblers to taxi drivers and toll collectors, the bots have come for the creative class. Yesterday’s fiction is becoming today’s reality, as each week we hear news of yet another generation of AI tools and wizardry being prepared to replace human workers. Programs such as DALL-E and Midjourney have ingested the collected art of all of humanity; they are now able to churn out endless reels of soulless imagery to feed our demand for custom-made illustration, everything from “a daguerreotype of Abraham Lincoln punching Joseph Stalin” to “pornographic iguana-sex rendered in the style of Pieter Bruegel the Elder.” As for the more text-oriented professions, OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google’s Bard, and a host of similar “generative AI” are able to produce reams of seemingly novel text on command, including restaurant (or film) reviews, business plans, academic articles, and even stories, poems, scripts, and screenplays. What began as a diversion has become an existential threat.

To their credit, the artists and storytellers of the world have long been among the most vocal critics of the unchecked spread of technology, even before they found themselves confronting automation and replacement. Whether spinning tales on a stage or around a campfire — or through the flickering light of a film projector — writers have warned of the dangers of technology unchecked, hoping to spray some cold water on these sparking Promethean fires before they burn out of control. From the lessons of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (whether Goethe or Disney) through Luddite anthems and pro-labor protest songs, right down to the modern-day fables of WarGames, The Terminator, Ex Machina, M3GAN, and just about every episode of Battlestar Galactica and Black Mirror, popular media has sounded a steady alarm to warn us of the inherent dangers of powerful automation, whether robotic, AI, or something entirely new. (Indeed, the very first use of the word “robot” a hundred years ago — in Karel Čapek’s R.U.R. — foretold of the coming robotic uprising and the eventual extermination of humanity at the hands of our own creation.)

How to mark the current moment, when global forces of labor, creativity, capital, automation, and invention are once again locked in struggle? We’ve decided to collect short reviews from a range of critics exploring films throughout the ages that explore the threats posed by robots and artificial intelligence. Some are outright Apocalyptic or dystopian works. Others present more nuanced, subtle, and blended takes. What will be lost, what can be preserved, are there ways we can control these changes in the service of a more humane “post-human” future? Or: are we even sure that we are actually human now…?

Given how rich this particular vein is, this list is more illustrative than exhaustive. Here is a rundown of a handful of thoughtful or thought-provoking films that are worth rewatching. Readers are sure to have their own contributions and we’d love to hear about as well – feel free to drop them in the comments.

A captivating scene from The Twonky.

The Twonky (Arch Oboler, 1953)

Though “screen time” is a relatively modern concept in regard to our relationship with technology, its associated anxieties have been with us for as long as we’ve invited screens into our homes. Consider Arch Oboler’s oddball 1953 comedy The Twonky, one of the earliest films ever made about television, and one of the strangest this side of Videodrome. Hans Conried plays a harried college professor whose wife leaves him alone for the weekend to set up their brand new TV set. What neither of them realize is that their newfangled device has a mind of its own; it skitters around the house on a set of table-legs, emits lasers from its screen (which it uses to light Conreid’s cigarettes), and neutralizes anyone who attempts to stop it by turning them into zombies muttering “I have no complaints.” Eventually, Conreid reasons that this “Twonky” (as his best friend, the hard-drinking local football coach, dubs it) is not actually a television at all, but rather a shape-shifting robot from Earth’s future, designed to keep the populace in line to serve a dictator named “Super Snake.”

At press time, Super Snake has yet to be elected to office, but The Twonky is nevertheless surprisingly prescient in many other ways. In 1953, the idea of a television which could anticipate its owners’ needs was a fanciful bit of whimsy; today, we walk past aisles of “smart TVs” at Best Buy without blinking an eye. Like modern algorithms which invisibly guide users toward the lowest common denominator, the Twonky zaps classical records and fine literature out of Conried’s hands, forcing him to listen to nothing but Sousa marches and read trashy paperbacks. When the Twonky overhears Conried bemoaning his loneliness with his wife out of town, it picks up a phone and requests a “human blonde” from the “Bureau of Entertainment,” eerily foreshadowing the contemporary targeted ads which seemingly prove that our devices are listening to our conversations. The Twonky is a deeply silly film, closer in spirit to Bewitched than Blade Runner, but its vision of the “helpful” technologies which end up running our lives remains timely 70 years later.

— Oscar Goff is the Editor in Chief and Senior Film Critic at Boston Hassle.

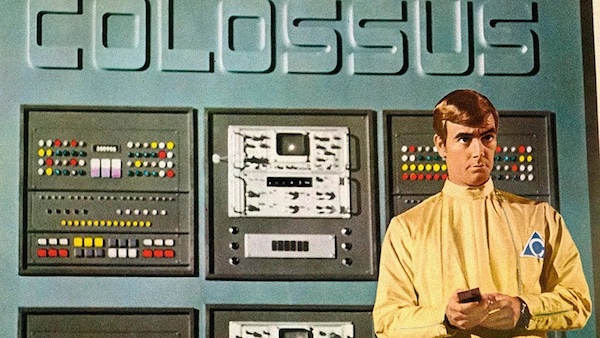

Art for Colossus: The Forbin Project

Colossus: The Forbin Project (Stanley Chase, 1970)

Based on a 1966 sci-fi novel, this cold-war thriller sets up a situation where the U.S. turns over control of its nuclear weapons to a computer. It removes the human element from war and, theoretically, makes us safer. But, as with Hal in 2001: A Space Odyssey, it’s all in the programming. Colossus discovers that there’s a Russian counterpart and demands to be linked to it, and starts to take punitive steps when such connection is not immediately forthcoming.

Dr. Forbin suggests that those working in his field should be required to read Frankenstein in order to consider what happens when science spins out of the control of the scientists. When I screened the film for my students and we reached the less than “happy ending” I would wish them pleasant dreams that night. This is the real fear of AI: we expect we will control our tools. But, when the tools can think for themselves, will they bother to listen to us?

— Daniel M. Kimmel is the author of Jar Jar Binks Must Die… and other observations about science fiction movies.

Are we home yet? Julie Christie in Demon Seed.

The House of Tomorrow: Demon Seed (Donald Cammell, 1977) and Smart House (LeVar Burton, 1999)

In celebration of its 75th anniversary in 1967, the Philco-Ford Corporation produced 1999 A.D., a short film showcasing its vision for the “House of Tomorrow,” which would be equipped with futuristic technology that would allow Americans to have live video chats with friends, pay their bills automatically, and set their thermostats to the perfect temperature year round. The house, the film suggests, would be operated by a central computer that could serve as a “secretary, librarian, banker, teacher, medical technician, bridge partner and all-around servant.” This para-utopian vision traded in the domestic Space Age optimism previously seen in cartoons like The Jetsons, but it came one year before 2001: A Space Odyssey, which helped introduce the specter of rogue A.I. into the cultural consciousness.

A decade later, Donald Cammell’s Demon Seed transformed the House of Tomorrow into a psycho-sexual nightmare, in which an advanced A.I. called Proteus goes from servant to captor. Its target is suburban housewife Susan (Julie Christie), for whom Proteus acts as an abusive partner, making excuses to her friends and creating proto-deepfake videos of her claiming to be fine. Why? The computer is planning to rape and impregnate her with a human-machine hybrid. In Demon Seed, A.I. transforms Edenic suburbia into a futurist dungeon – one of pop culture’s many warnings to come about the unknown dangers of advanced technology.

A scene of mutual happiness in Smart House.

By 1999, the real life smart homes of Alexa and affordable IoT appliances were nearer to becoming a reality than many realized; Philco was only off by about a decade or so. Still, fears of AI in the nuclear household persisted. The LeVar Burton-directed Disney Channel Original Movie Smart House created a kid-friendly version of Demon Seed, in which a single-parent family wins a free computer-operated home. Thirteen-year-old Ben’s (Ryan Merriman) mother has died, and to fill the void he trains the house’s central AI, PAT (Katey Sagal), on footage from old ’50s sitcoms (pastiches of Father Knows Best and Leave It to Beaver) to teach her how to be a perfect matriarch. PAT goes in another direction and begins to resemble Proteus, imprisoning the family via an overbearing maternal instinct and a hyperbolic fear of the outside world. Researchers warn of AI reflecting the biases of its human programmers and users. Smart House dramatizes that prediction: the once “rational” computer succumbs to the patriarchal beliefs that drive American pop culture and absorbs the paranoia spread by television news.

— Brad Avery is a journalist and writer based in Boston. He is a member of the Boston Online Film Critics Association.

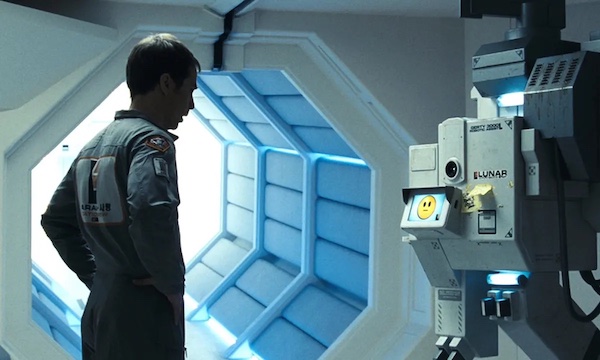

A scene of mutual uncertainty in Moon.

Moon (Duncan Jones, 2009)

Moon is the debut effort of filmmaker Duncan Jones, who wrote the story and directed. The narrative posits a near-future that is not so much about AI controlling human beings, but a dark anti-capitalist vision of how corporate America will use such technologies to exploit us for profit. One human’s experience is presented … sort of. Sam Bell (a tour-de-force performance by Sam Rockwell) is the lone technician for a mining outfit that is harvesting helium from the moon for fusion reactors back home on earth. Sam monitors the mostly automated operations of the equipment, occasionally checking on and fixing malfunctions, during a three-year stint on the moonbase. His only companion and helper is Gerty (voiced by Kevin Spacey), an AI who ensures that Sam stays healthy.

The big twist in Moon is that Sam Bell is not Sam Bell, not really. He is a clone of Sam Bell, who is either dead or back on earth (it is never settled). The clones are how the mining company makes us of infinite free labor. When things go awry on the base, the machinations of the plot eventually gives us two Sams. In fact, the base is outfitted with thousands of Sam clones in cold storage, since each clone can only function for three years before degrading and being destroyed by the base’s technology. Gerty, meanwhile, is programmed to help Sam, even if there are two Sams. (The existential side-story of “Sam1” and “Sam2” relating to each other is fascinating on its own, as both realize what it means to be a fully conscious clone with the real memories of the original Sam. Plus we get two Rockwells playing ping pong with each other, which is never a bad thing.)

In regard to AI, the film allows for a glint of hope. Humans can overcome the crush of plutocratic hegemony — by using technology against itself. Gerty at first appears to be a HAL9000-like threat to Sam, siding with the corporation and doing their bidding early on. But ultimately the program enables Sam (and Sam) to undermine the system that is degrading them. Gerty cannot allow Sam to die and, in an ambiguous turn of events, it turn out the computer cannot distinguish between the two Sams. As such, Gerty’s programming only serves to bring about its own downfall. The Sams sense this: when it becomes a choice between Sam’s health and the well-being of the moon base and mining operation, Gerty will choose to help Sam.

The production design by Tony Noble uses a cool palette of greys and blues for the moon base, but tosses in some neat counter-touches. Aside from Gerty’s voice, the machine is represented by a small screen with a bright yellow emoji that reflects Gerty’s mood: a smiley face most of the time if Sam is happy and healthy. Eventually, there is expressionlessness, followed by confusion. Gerty’s limited emotional landscape is overpowered by the very human presence of Sam: Rockwell is moody, sardonic, and self-aware in a way that Gerty could never be. Sam’s humanity — clone or not — is never called into question. He is not a machine. He is not artificial. And it is the character’s humanity that shapes the movie’s satisfying, if troubling, conclusion.

— Neil Giordano

Joaquin Phoenix longing for his significant other in Her.

Her (Spike Jonze, 2013)

Much of the animosity towards artificial intelligence these days tends towards practical matters, with loss of livelihood being paramount. But, prior to the recent controversy surrounding the writers and actors strike in Hollywood, most people felt artificial intelligence to be a mild existential threat. This was technology that re-shaped our very humanity because it could do so many things, including mundane chores like shopping, cleaning, and cooking. Some people are thrilled to leave these dull tasks to others; others find such routines and rituals meaningful, even and comforting. Even more challenging: this technical revolution clearly has implications for gender roles that even today, are still mired in traditional sexist grooves. It is exciting and progressive to think that we might have the opportunity to reinvent stale customs and assumptions (i.e., women shouldering the main burden of domestic duties). Even love might take on new meaning.

With the 2013 film Her, Spike Jonze dabbles in the dystopian notion that artificial intelligence can fulfill our every need, including, for those lonely enough, the role of a romantic soulmate. Joaquin Phoenix plays Theodore, a recently-divorced writer who works for a virtual greeting card company that creates digital messages for all occasions: a sort of troubadour for the age of technology. He tries dating, but can’t quite figure out what he’s doing wrong. When his new operating system and virtual assistant, Samantha, proves to be not only competent and helpful but warm and personable, he finds himself smitten.

Voiced by Scarlett Johansson, Samantha’s mercurial, soulful personality carries unexpected appeal. But when Theodore discovers he is one of many who are also romantically involved with this virtual dynamo, his sense of being chosen, of being special, is betrayed. Artificial intelligence is an affront to the idyllic belief that lovers are drawn together by fate, by a shared sense of discovery and recognition. Theodore’s loneliness is briefly eclipsed by what he perceives to be a ‘real’ relationship. This dissonance mirrors the odd phenomenon of dating apps; they make information and engagement readily available, but true connection remains elusive. With its carnival dusk color palettes and intense, nuanced performances, Her invests its cold dystopia with suprising pathos as well as haunting sense of inevitability. As the sun goes down each day on the film’s city of glass and pedestrian walkways, there is a sense that the self, the true one that melds body and heart and mind, is being reinvigorated and recharged. Emotional autonomy is still there for the choosing. At least, for now.

— Peg Aloi is a freelance film and TV critic who has an uneasy relationship with technology.

A scene from #PostModem

#PostModem (Jillian Mayer, 2013)

Much of visual artist Jillian Mayer’s body of work concerns the relationship between humanity and technology, particularly the absurd intrusions modern tech makes into our lives. Take for instance her short film Hot Beach Babe Aims to Please (2014) in which Mayer emerges from the ocean only to be chased by a swarm of cursors, or her Makeup Tutorial (2013) where, in the language of YouTube vloggers, she instructs viewers on how to paint their faces with jagged patterns to confuse and hide from facial recognition devices.

Her 2013 collaboration with Lucas Leyva, #PostModem, is among her most enjoyable film projects — a 15 minute sci-fi musical inspired by the theories of futurist Ray Kurzweil and the concept of the technological singularity, the theorized moment when artificial intelligence, capable of nigh-infinite self-improvement, surpasses human intelligence. In #PostModem, Mayer becomes immortal by uploading her consciousness to an open internet website called MegaMegaUpload (achieved by drawing the AOL logo on her face and drinking a blend of orange juice and her own hair filtered through a CD-R disc). What will she do throughout eternity? Watch infomercials alongside her digital doppelganger, a cheap digital avatar a la “Second Life” or “The Sims.” #PostModem stands as one of the sharpest satires to date on the sputtering of Mark Zuckerberg’s Metaverse. Instead of Oculus headsets, Mayer’s super-intelligence future involves crude at-home surgery and implanting motherboards into one’s own forehead (now that’s biohacking). Ultimately, the film questions what enlightenment, if any, will be gained with our diaspora to VR.

— Brad Avery is a journalist and writer based in Boston. He is a member of the Boston Online Film Critics Association.

Chiwetel Ejiofor and Emilia Clark as proud parents in The Pod Generation.

The Pod Generation (Sophie Barthes, 2023)

In the 1965, The Rolling Stones sang:

Kids are different today. I hear every mother say/Mother needs something today to calm her down/And though she’s not really ill, there’s a little yellow pill/She goes running for the shelter of her mother’s little helper.

Meprobamate, marketed as Miltown, helped relieve a mother’s “insomnia, anxiety, and emotional upsets.” Today, wet nurses are out of fashion, day care costs are prohibitive, and mothers juggle work, kids, social life, parenting groups, and husbands. From stretch marks to intimacy, sleep deprivation to post-partum depression, motherhood can be a bitch. What’s a mom to do?

Sophie Barthes’ new film The Pod Generation imagines what it would mean for women to cast off the burdens of childbearing through the use of synthetic egg-shaped pods. With the couple’s permission, the company Pegazus will arrange to have a baby raised in a Womb Center, where it is nurtured with music, taste sensations, and all the nutrients necessary for a healthy ‘birth.’ A helpful strap-on device allows dad or mom to ‘carry’ the pod/child for brief periods. There is a downside: the child won’t dream. As the spokesman for the company explains “dreams are not reliable analytical material – that’s so 20th century.”

It is a gleaming future of 3-D printers, oxygen inhalers for fresh air, and a Siri/Alexa type virtual assistant, named Elena, that can help with such mundane tasks as preparing breakfast and choosing outfits for the day while also maintaining an individual’s “bliss index” based on voice and behavior patterns. The film’s conclusion is hurried but that didn’t bother me because the point had been made: we lose something valuable when technology provides shortcuts to chores that were once part of a normal life. Of course, there is a need for surrogate parenting, in vitro fertilization, and so forth, but outsourcing motherhood to plastic pods (which are shaped to fit corporate imperatives) is a sharp parody of the obsession with convenience. The relentless progress of technology undercuts the value of imagination, labor, and even physical and mental duress.

Will AI replace or even enhance art and creativity? One answer is posed by Noah Baumbach’s film While We’re Young. At one point, Adam Driver’s Jamie asks Ben Stiller’s Josh about the ingredients of a certain dessert. “Let’s look it up,” advises Josh. Waving his phone and giggling, Jamie, the hipper of the two, responds: “That’s too easy. Let’s just not know what it is.”

—Tim Jackson is a Boston musician, actor, and retired college teacher, currently a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics.

Ezra Haber Glenn is a Lecturer in MIT’s Department of Urban Studies & Planning, where he teaches a special subject on “The City in Film.” His essays, criticism, and reviews have been published in the Arts Fuse, CityLab, the Journal of the American Planning Association, Bright Lights Film Journal, WBUR’s ARTery, Experience Magazine, the New York Observer, and Next City. He is the regular film reviewer for Planning magazine, and member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. Follow him on https://www.urbanfilm.org and https://twitter.com/UrbanFilmOrg.

Tagged: #PostModem, AI, Colossus: The Forbin Project, Demon Seed, Her, Moon, robot movies, Smart House, The Pod Generation

Also worth watching: the Twilight Zone episode “The Brain Center at Whipple’s.”