Film Review: “Sloane: A Jazz Singer” — Making the Most of Your Gift

By Steve Provizer

Sloane: A Jazz Singer is a very sweet film that never cloys because of the singer’s naturalness, honesty, occasional self-deprecation, and sense of humor.

Sloane: A Jazz Singer, directed by Michael Lippert. The documentary screens at the Newburyport Documentary Film Festival on Sept 17 at 6 p.m. at the Firehouse Center for The Arts.

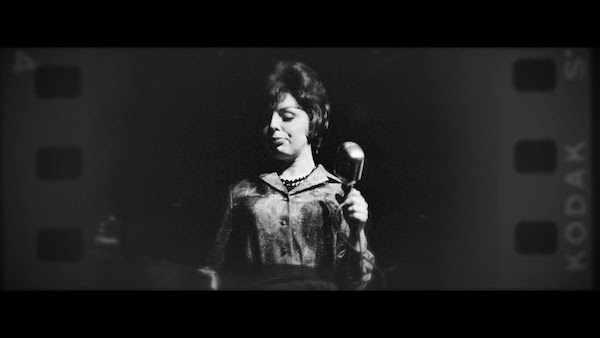

Carol Sloane at Newport, 1961. Photo: courtesy of Sloane: A Jazz Singer

In the first scene of this documentary, we follow Carol Sloane from a parking lot into a supermarket. The store manager, noticing the hubbub, asks what’s going on and Sloane explains they’re shooting the story of her life and career. After a brief exchange, Sloane asks him to retrieve a cane she’d left on her last trip to the market. He brings back a collection of canes and she finds hers. The manager says, “Are you famous and I just don’t know it?” “Well, if you like jazz,” she responds, “you might know who I am.” He says, “I like jazz. What instrument did you play?” Sloane says, “I’m a singer” and sets off to do her shopping.

This is a perfect setup. We immediately see Sloane as a very down-to-earth, likable person, someone who doesn’t expect the royal treatment (how many jazz musicians do?). But we also sense that this is someone who may be chafing beneath the surface. As Sloane: A Jazz Singer continues, we increasingly see a person who is negotiating between various levels of confidence, and high self-expectations interlaced with vulnerability. She is aware of her talent and the importance of what she’s accomplished, but insecurity is always lurking around the edges.

The film adeptly uses the tools in the documentary grab bag, intercutting new and old video and film footage, radio interviews, still photos, and b-roll of natural and urban scenes to establish a mood. There are talking heads, but for the most part (see exception below), they make their points and exit the screen fairly quickly. Some of Sloane’s interchanges with the film’s director Michael Lippert are left in, and they are well chosen to illuminate aspects of Sloane’s personality.

At a young age, Sloane knew she had talent. She was enchanted by Ella Fitzgerald, Carmen McRae, Billie Holiday, and Sarah Vaughan. She recalled, “I wanted to know how they did it. I wanted to be able to persuade people the way they were persuading me.” By age 14, she “knew what her destiny was.… I said someday I’m going to live in New York City.”

Every clip we see of Sloane singing cements the case for how good a singer she was. She was known for her subtlety and depth of interpretation, but she also had the vocal range to do what the gig called for. There is a clip from the TV show Talent Scouts in 1962 in which she was almost a “belter” in the Judy Garland mode.

Carol Sloane sings at Birdland in 2019. Photo: courtesy of Sloane: A Jazz Singer

The film introduces a new theme: her upcoming gig at the jazz club Birdland, where she will make a live recording. She says, “It’s important to me to prove I can still do it.” At this point, the film begins to cut back and forth between Sloane’s preparations for the Birdland gig and telling her back story.

In 1957 she joined the Larry Elgart band and this got her to NYC. In 1960, Jon Hendricks asked her to sub for Annie Ross in Lambert, Hendricks & Ross. Her appearance at the 1961 Young Artists event at the Newport Jazz Festival got her a contract with Columbia Records. What put it over was the fact that the pianist didn’t know the verse to “Little Girl Blue,” so she sang it a cappella — with emotion and on pitch. (Many years later, I heard her sing all of “Stardust” a cappella and it was stunning.)

We see Sloane taking in her mail, watching TV in her humble apartment, and searching for a notice about her upcoming gig at Birdland in the New Yorker. (There was none.) The film alternates this drama with looks at her high-flying adventures in show business. Sloane landed some exposure on TV and gigged with Lenny Bruce, Richard Pryor, and Phyllis Diller. She got to hang out with the Beatles and the Stones, but knew they were undermining the whole jazz edifice. As she says, “Jazz was gonna take a direct hit from these kids.”

It never addresses the issue directly, but Sloane: A Jazz Singer begs the question of why an artist of Sloane’s caliber never received her due. The filmmakers try to supply some reasons by emphasizing the hit Sloane’s career took in the ’60s. They turn to Michael Weaver, billed as a “Performing Arts Historian,” who makes the shaky case that jazz “was associated with drugs and prostitution.” And that it wasn’t until “the mid ’60s that you could even say the word jazz in a school curriculum.” Then there’s the usual pabulum about the kids having to find their own music and reject mom and dad’s. Too simplistic and broad a brush for my taste. The film also turns to Mark Sendroff, “Entertainment Attorney.” He says, “I don’t think she had the exposure that other artists had.… She was on television frequently, but didn’t have her own television situation, she didn’t make movies.” But why didn’t she get these opportunities? I’m not sure that question can be answered, but Sendroff’s explanation and to some degree Weaver’s come off as excess baggage.

It never addresses the issue directly, but Sloane: A Jazz Singer begs the question of why an artist of Sloane’s caliber never received her due. The filmmakers try to supply some reasons by emphasizing the hit Sloane’s career took in the ’60s. They turn to Michael Weaver, billed as a “Performing Arts Historian,” who makes the shaky case that jazz “was associated with drugs and prostitution.” And that it wasn’t until “the mid ’60s that you could even say the word jazz in a school curriculum.” Then there’s the usual pabulum about the kids having to find their own music and reject mom and dad’s. Too simplistic and broad a brush for my taste. The film also turns to Mark Sendroff, “Entertainment Attorney.” He says, “I don’t think she had the exposure that other artists had.… She was on television frequently, but didn’t have her own television situation, she didn’t make movies.” But why didn’t she get these opportunities? I’m not sure that question can be answered, but Sendroff’s explanation and to some degree Weaver’s come off as excess baggage.

There were a lot of rough patches in Sloane’s life. At one point, she says, “Too bad, but art don’t pay.… Frequently I was on the verge of being evicted.” In the early ’70s, she relocated for a gig in Raleigh, North Carolina, at The Frog and The Nightgown, and worked as a legal secretary. That job ended shortly after, and she was hired at a law firm in Boston. But then Stephen Barefoot, who opened Stephen’s, After All in Chapel Hill, called Sloane and she went back to North Carolina. A year later, that club closed, leaving her alone again, “with enough money [for me] to buy cat food and scotch.”

The question of being a woman in jazz is not addressed in the film. Sloane does say, however, “Well, I never felt any kind of resentment at all because I was a white woman.”

She had an affair and began to live with pianist Jimmy Rowles, who was a heavy drinker. He randomly went out on tours, leaving her alone. And he did not keep in touch: “I was disappearing.… I felt ashamed.… I got myself in this mess and I should be able to get myself out of it.… So I took a whole lot of sleeping pills…” Rowles called someone who got her to the hospital. “I don’t remember much of anything except that I slept very solidly for two days.”

Out of the blue, she called Buck Spurr in Boston, who ran the Starlight Roof jazz club in Kenmore Square. Romance blossomed and they married. At age 50, her career started to regenerate. Then Spurr was diagnosed with cancer, followed by dementia. She cared for him and stopped performing.

In the wake of his death, she drank and put on a lot of weight. She says that pianist Bill Charlap told her “that if I didn’t go back to singing, I was committing a sin; neglecting my gift.” She began to gig and record and started to coach vocalists.

The preparation for the Birdland gig with pianist Mike Renzi accelerates. The day of the show arrives and Sloane says that she is “absolutely terrified.” Birdland’s management tells her that the gig is completely sold out, which she has trouble believing. She and Renzi are joined on stage by Jay Leonhart on bass and Scott Hamilton on sax. They kick off with “Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams” followed by “I’ve Got a Right to Sing the Blues.” When they finish the set, the audience gives Sloane the full-throated ovation she hoped she’d be able to earn. It appears to have been her last hurrah: the closing credits tell us that she spent the next two years in “a senior care center near Boston.” She died on January 23, 2023.

Sloane: A Jazz Singer is very sweet film that never cloys because of the singer’s naturalness, honesty, occasional self-deprecation, and sense of humor. I’ll close by quoting her: “I think all of us think ‘how long have I got to live and enjoy friends and everything that life gives us — a good meal, a good movie, a good laugh, a good journey.…Feeling, yeah, I’m doing what I was put here to do.’”

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

I was there in Chapel Hill during that one glorious year of the Stephen’s, After All club. It was fantastic. The local public radio station jazz DJ, Gary Shivers, was friends with Carol Sloane and promoted her regularly and hard as one of the all-time greats. North Carolina respected Sloane and treated her well during the brief time she was there.

Interesting, Allen. The film describes it as a very happening scene. Stephen Barefoot says the club did great when they booked big names but otherwise, much less so.

Good to read about Ms. Sloane. Interesting piece! I know I did a story about her in The Boston Herald in the ’80s, and may have reviewed her at the Starlight Roof. What a delicious little jazz scene that was. (I think it was booked by Fred Taylor.) Thanks for bringing back the name of Buck Spurr (how could I have forgotten a name like that!?) As far as jazz having a bad name in the 1960s public schools… I recall fondly being part of a bunch of high school actors who were lucky enough to be sent to see the filming of a jazz TV show in the late 1960s. So, yes, they were attempting to get teenage rock fans to open their ears to jazz. But there was no shame to the genre in schools. I recall seeing The Modern Jazz Quartet and the Cannonball Adderly Quintet (with Nat Adderly and Joe Zawinul!) What an intro to jazz!