Visual Arts Review: “Van Gogh’s Cypresses” – Seeing the Forest for the Trees

By Melissa Rodman

Ah, the trees! They are the focal point, the organizing principle, of this tight exhibition, which in three parts tracks Van Gogh’s productive yet challenging sojourn in southern France, from Arles to Saint-Rémy.

Van Gogh’s Cypresses, curated by Susan Alyson Stein, Engelhard Curator of Nineteenth-Century European Painting at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. On view at the Met in New York City through August 27.

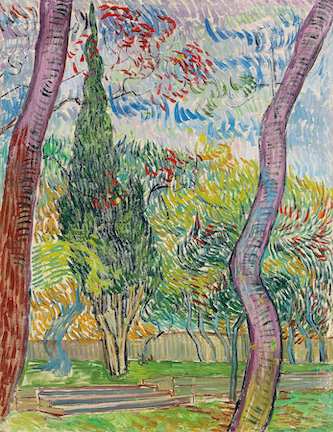

Vincent van Gogh, Trees in the Garden of the Asylum, October 1889. Private Collection. Photo: courtesy of the Met

At the start of the exhibition Van Gogh’s Cypresses, we encounter a letter. “[J]e veux commencer par te dire que le pays me paraît aussi beau que le Japon, pour la limpidité de l’atmosphère et les effets de couleur gaie,” Vincent Van Gogh wrote to his artist friend Emile Bernard on March 18, 1888. (“I want to begin by telling you that this part of the world seems to me as beautiful as Japan for the clearness of the atmosphere and the gay color effects.”) Van Gogh is extolling the scenery of Arles, a city along the Rhône river in Provence, where he had arrived the previous month to paint. He envisions a reality in which other artists would join him.

In this missive, van Gogh moves beyond description. A pen-and-ink sketch takes up the top third of the browned paper. A drawbridge spans the river, and two couples — sailors and their lovers — promenade on the quay. The artist annotates how he’d go about coloring a fuller study: pink for the path, green for the grass, lilac for the bridge, and “un énorme soleil jaune” (“a huge yellow sun”) whose rays would brighten the sky. A tree stands at the water’s edge.

Ah, the trees! They are the focal point, the organizing principle, of this tight exhibition, which in three parts tracks van Gogh’s productive yet challenging sojourn in southern France, from Arles (February 1888–May 1889) to two periods in Saint-Rémy (May–September 1889 and October 1889–May 1890). The exhibition assembles just over 40 pieces from public and private collections. And with the cypress motif as a visual anchor, the viewer can appreciate the evolution of van Gogh’s work as well as its consistency.

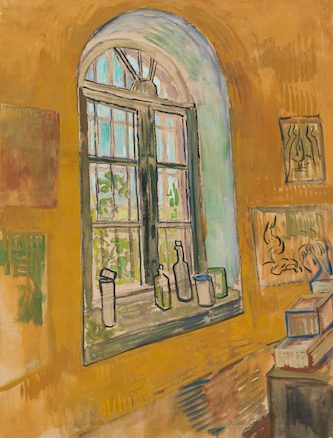

Vincent van Gogh, Window in the Studio, October 1889. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. Photo: Vincent van Gogh Foundation

Cypresses have a constant presence, but their prominence varies. In van Gogh’s early works in Arles, for instance, the cypresses are supporting players in the landscape, not the stars. They stand as calm sentinels next to quaint bridges, not only in the sketch for Bernard but also in two similar compositions, an oil on canvas (Drawbridge, May 1888) and a drawing (The Langlois Bridge, July 1888). They border peach and apple orchards (Orchard Bordered by Cypresses and Orchard with Peach Trees and Cypresses, both April 1888). They peek out from behind lush flowerbeds (Garden at Arles, July 1888 and Garden with Flowers, July–August 1888). These compositions do not diminish the trees’ power. There is something reassuring, grounding, about the cypresses in these scenes. The dark, slender trees contrast with the flat, flaxen tone of everything around them — gentle giants presiding over the countryside.

This first room also presents two more of van Gogh’s illustrated letters, both owned by the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. One letter went to the artist’s brother, Theo, and the other to his sister, Willemien. The letter to Theo features a characteristic pair of figures — a hatted man and full-skirted woman — walking alongside a row of cypresses. The letter to Willemien contains multiple sketches, a tableau of women in front of cypresses and a solitary woman reading a book. These documents are fascinating, but one craves additional biographical context, say, a line or two about the nature of van Gogh’s relationships to his siblings. (For those curious about the correspondence, the Van Gogh Museum and the Huygens Institute created an incredible resource, The Van Gogh Letters Project, where you can browse and zoom in on the artist’s correspondence at your leisure.)

The final two paintings in the Arles room presage intriguing shifts in style. We learn that van Gogh painted Still Life of Oranges and Lemons with Blue Gloves (January 1889) shortly after he sliced off his ear during a fraught interval with Paul Gauguin, who was staying with him in Arles. Cypress fronds cradle a bowl of fruit, flanked by soft indigo gloves. Both the cypress and citrus have approximately the same dimensions — the largest area of the canvas devoted to cypress so far. In Landscape Under Turbulent Skies (April 1889), darkening clouds — rendered with short impasto streaks of mauve — gather over a flowering field, with just a few cypresses tucked into the horizon.

Vincent van Gogh, The Draw-bridge at Arles (Pont de Langlois), 1888. Oil on canvas. Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv Cologne

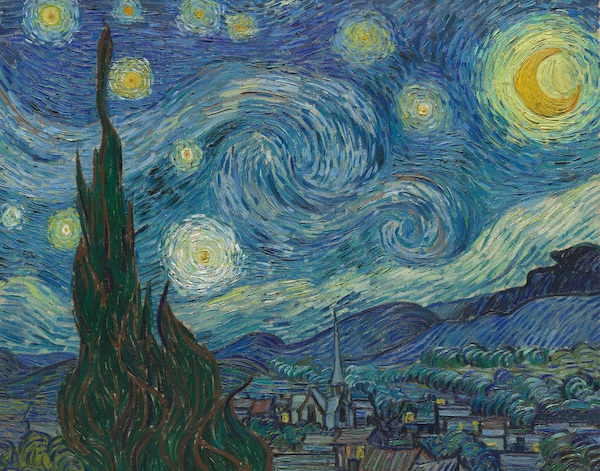

Van Gogh checked himself into a psychiatric asylum in nearby Saint-Rémy the next month, May 1889. At this point, his compositions begin to embrace drama. Landscape from Saint-Rémy (June 1889) has a foreboding, storybook quality; windswept grass dominates the foreground, undulating hills curve right into the clouds. Also in June 1889, van Gogh painted The Starry Night, that swirling canvas of midnight sky, looming over a quiet town, punctuated by the dark steeple of a cypress.

Next to The Starry Night are two iterations of the same scene, “seen together for the first time since 1901,” as one label attests: Wheat Field with Cypresses (June 1889) and A Wheatfield with Cypresses (September 1889). Here is a remarkable opportunity to make a close, side-by-side comparison. But there is a problem: The paintings are hung a bit too far apart. In each, the cypresses tower above a crop of wheat and stretch into the whirling clouds. “C’est la tache noire dans un paysage ensoleillé,” Van Gogh wrote to Theo on June 25, 1889, “mais elle est une des notes noires les plus intéressantes, les plus difficiles à taper juste que je puisse imaginer.” (“It’s the dark patch in a sun-drenched landscape, but it’s one of the most interesting dark notes, the most difficult to hit off exactly as I can imagine.”)

Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, Saint Rémy, June 1889. Oil on canvas, 29 x 36 1/4″ (73.7 x 92.1 cm). Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest. Photo: courtesy of the Met

The last portion of the exhibition finds van Gogh ill again. His palette has taken on a rather dank hue. Among the canvases, A Walk at Twilight (May 1890) stands out. Underneath a teal-and-creamsicle sky, van Gogh’s omnipresent couple strolls on a hillside studded with shrubbery, with cypress trees shooting upward in the background. The couple inhabits what feels like a tense dream. Soon after painting this image, van Gogh will leave Saint-Rémy and travel north to Auvers, where he will die. In October 1889 he wrote to Theo: “[I]l est difficile de quitter un pays avant de prouver par quelque chôse qu’on l’a senti et aimé.” (“[I]t’s difficult to leave a land before having something to prove that one has felt and loved it.”) This exhibition offers indelible proof of his passion for the south of France.

Melissa Rodman is a journalist and critic based in New York.

Ah, Thank you Don McLean