Visual Arts Review: Robert Barry and Martin Puryear’s Fountain of Youth

By Helen Miller and Michael Strand

Despite their stylistic differences, Robert Barry and Martin Puryear share a similar goal: to include us in their respective inquiries into the nature of mind and liberty, but not do the work for us.

Robert Barry and Martin Puryear at the Krakow Witkin Gallery, Boston, through June 10.

Robert Barry exhibition view. Photo courtesy of Krakow Witkin Gallery

At first glance, Robert Barry’s acrylic text paintings offer little in the way of painterly pleasures. And while Martin Puryear’s exquisitely printed shapes and patterns are more immediately rewarding, they make their considerable demands as well. Still, these shows pose a challenge that it is hard not to love, partly because they both set out to defy instant gratification. Despite their stylistic differences, Barry and Puryear share a similar goal: to include us in their respective inquiries into the nature of mind and liberty, but not do the work for us.

Barry and Puryear have been among the more successful experimental artists in recent memory. But what is the relationship between their first, often bold, steps in the art world, their association with 20th-century avant-garde movements like conceptual art and minimalism, and what we see now? Does their latest work meditate on the same things? How has their process developed or changed? These shows are not retrospectives, so it is fair to ask: are Puryear and Barry still of the moment?

Robert Barry, Turquoise Mirrorpiece, 2020. Enameled and etched glass, edition of 15, 30 x 30 inches. Photo courtesy of Krakow Witkin Gallery

In 1969, at the height of conceptual art, Barry famously released the five noble gasses — helium, neon, argon, krypton, and xenon — into the atmosphere around L.A. and called it a show. There are a handful of charmingly nondescript photographs and a poster to prove that he did it. Among other things, the gesture was indifferent to spectacle, symptomatic of the artist’s modest (if brilliant) approach to institutional critique, if we can even call it that. This is the same guy who invited people to exhibitions at closed galleries; the invitations simply read: “During the exhibition the gallery will be closed.”

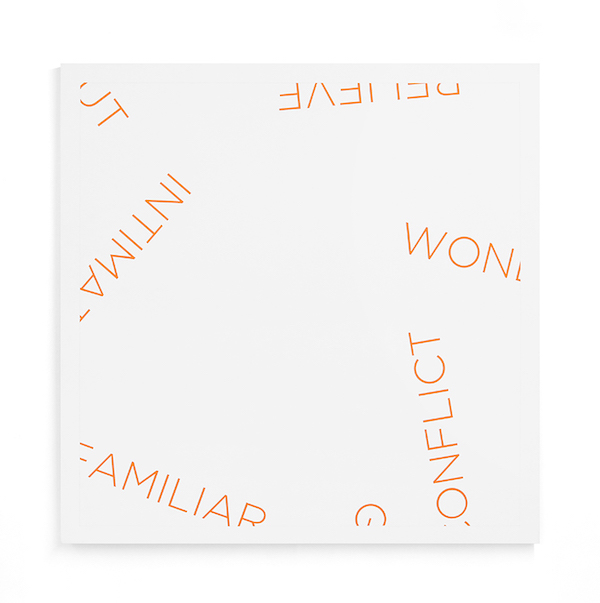

Some have understood this kind of work as an attack on the “commodification of the art object,” but in interviews Barry comes across as more practical than didactic. The work itself is more poetic than knowing. Often the “happening” is elsewhere — around the corner, in the margin of a drawing, or even along the edge of a canvas, where the letters of some words in the paintings in this show — such as the 60 x 60-inch pair of Untitled (2022) and Untitled (2021) — have been painted using prefabricated vinyl stencils. In Turquoise Mirrorpiece (2020) Barry etches and embeds his words in enameled glass. “Almost,” “Meaning,” “Somehow,” “Going,” “Beyond,” and “Unfamiliar” are arranged at various angles. The result is a surprising range of effects — from dropped shadows to what appear like dropped halos — that invite the viewer to reflect. If you’re lucky, you’ll catch the gallery lights twinkling between words or the auratic frame that appears like a solar eclipse, depending on where you’re standing. The words “Almost” and “Beyond” are themselves off-center, directing our thoughts away from the present while simultaneously instantiating it.

Look left and the bright orange of Untitled (2022) hits you like a blinding after-image. This is color theory, but at its most unselfconscious and deceptively matter-of-fact. The absence of lush oil pigments or bravura may have something to do with the disarming effect, although, if you stay with the work long enough, you will also observe some endearing “touch-ups,” passages of opaque clementine-colored paint where the sky-white blue text must have seeped out from underneath the stencil and required extra coverage.

In some ways, Barry remains as underground today as when he did his early experiments, save in art school circles. This is in contrast to Puryear, who has remained a familiar name in the mainstream art world for over 50 years. The story is often told of the acclaimed sculptor’s formative time as a Peace Corps volunteer in Sierra Leone, where he learned firsthand the craftsmanship of the local woodworkers, weavers, and potters. As a young painter, Puryear was struck by the facility and humility of his hosts’ carpentry, which influenced his embrace of a constructive, additive way of making 3D work.

The inseparability of form and function in everyday craft fascinated, inspired, and stuck with Puryear. It instilled in him a respect for maker and made, which subsequent study and fellowships in Sweden and Japan reinforced. At the same time, the anonymity of the skilled artisans sparked in the emerging artist an appreciation of the communal and universal value of creativity, not to mention the need for modesty and a healthy dose of skepticism regarding fame.

At the time, such exposure and experience came into conflict with what Puryear saw in the “outsourcing” embraced by American minimalism. Decades later, the artist would find the labor required to execute public sculptures on his own to be mind-numbing and all-consuming, to the point that it undercut his development as an artist. Ever since, Puryear has availed himself of assistants on projects big and small.

Martin Puryear, Untitled, 2022. Intaglio, edition of 39, 28-5/8 x 29-1/2 inches. Photo courtesy of Krakow Witkin Gallery

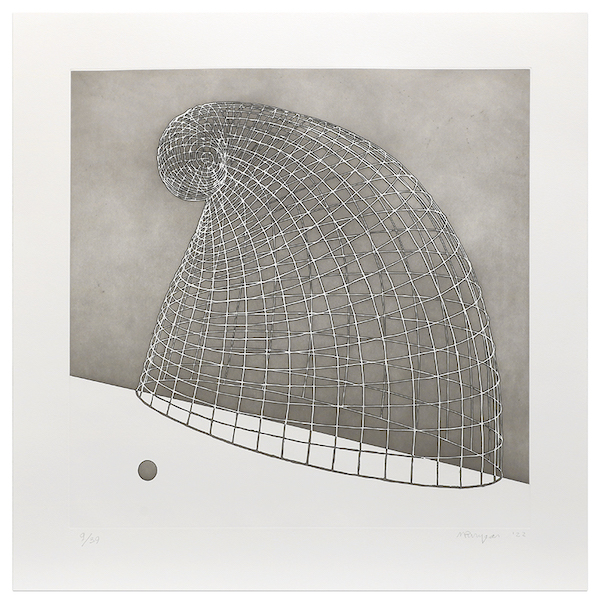

While some things have changed, Puryear’s continued devotion to craft is apparent in almost every aspect of Untitled (2022), a 22-¼ x 23-⅝ inch near-square intaglio print featured in the show. The Fibonacci curve topping the transparent shell-like figure is characteristic of many natural forms. The mark-making resembles the lines of frayed straw commonly found in basketry. The work’s textural detail feels more intentional than residual — crafty, for lack of a better word, even illustrative.

In addition to surface texture, Puryear has always been interested in space and scale. Untitled (Navy Pier) (1985), the fifth and final work in the show, depicts a public enclosure: a pier in the form of an inverted canoe that stretches to the horizon. In the center foreground, silhouetted figures and their shadows appear to be set in an architectural rendering, supplying a sense of the pier’s massive scale. The glow that surrounds the figures is more a feature of landscape painting; the emphasis on nature evokes a feeling familiar to anyone who has spent time pondering the immensity of the ocean.

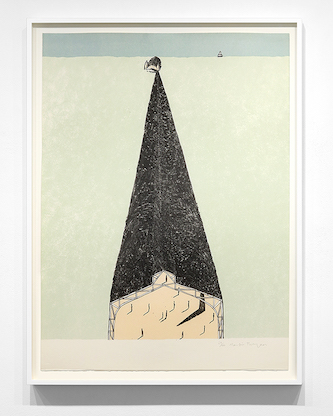

Martin Puryear, Untitled (Navy Pier), 1985. Lithograph in colors on wove paper, edition of 100, 35-1/4 x 27 inches. Photo courtesy of Krakow Witkin Gallery

Despite its having been made decades prior to the other prints in the show, and despite its use of color — sea green, blue, black, and buff on wove paper — this earlier, more representational piece is prescient of Puryear’s later work. The web-like support beams of the canopy remind us of the organic, intersecting lines of Untitled (2022). The print of the pier is testament to the artist’s career-long interest in the relationship of interior and exterior space. It fits like a key in the keyhole shape of Untitled (State 2) (2016), smartly hung next to the Fibonacci shell. Seeing the two prints together, we might view them as bookends for Big Bling (2016), Puryear’s largest temporary public sculpture, initially exhibited in New York’s Madison Square Park, then in Philadelphia, and now at MASS MoCA.

Puryear’s Beggar’s Bowl (2002-03) is a small woodcut on Japanese paper featuring a refined two-tone sketch of a somewhat oblong bowl. The piece is not entirely figurative, but neither is it wholly abstract. We can see it, instead, as an homage to craft that suggests a yearning for liberation and social justice. Actual “beggar’s bowls” (kashkul) are part of an Islamic tradition: they signify aid to the wanderer and the poor. Meanwhile, in Untitled (2022), Puryear etches a sculptural motif that resembles a Phrygian cap, the kind of high-topped knit cap, typically red, that looks like a sock and droops over a little in the front. The hat was associated with the peasant dress of the sans-culottes, instigators of the French Revolution, and quickly became a symbol of emancipation across the Atlantic World. It was later adopted by the Abolitionist movement in the US.

When Puryear takes up these symbols, he does not go about straightforwardly presenting or reconstructing them. Rather he embraces a kind of deconstruction. We can see this in the blueprint-like depiction of the Phyrgian cap and the X-ray-like image of the beggar’s bowl. In both cases, Puryear seems to ask: What do these symbols really signify? Can they contribute to social justice as they claim? In deconstructing how things are made and what they are made of, Puryear discovers the new in recombination — in a process more seamless than collage or assemblage, he juggles different histories and practices, mixing softwoods and hardwoods you would never find growing in one location.

A nutshell from the coco de mer palm starts in the Seychelles Islands and comes ashore along the beaches of southern Iran. It will be used in the carving of a kashkul. This part of the story is not lost on Puryear, who has long had an interest in boats and boat-making. Nor is the seafaring shell as a symbol for the dervish’s spiritual course lost on the curators of these productively paired exhibitions.

Around the corner from Puryear’s Untitled (Navy Pier) (1985), another piece, this one by Barry, has been installed for the first time. In the deep cerulean blue of Two Wall Corner Piece (1984), words cut out of metallic vinyl shimmer like moonbeams, playfully appearing and disappearing as we approach. Positioned as a compass or the hands of a clock, they follow a circular logic and, much to our delight, appear upside down for half of the rotation. Words like “Life” and “True” are brought down to earth by phrases like “Had To” and “Another Thing.” Their radiance harkens to the lighthouse in Puryear’s print, and the displacement of its iconic beam onto the perspective of the pier.

Robert Barry, Untitled, 2021. Acrylic and graphite on canvas, 48 x 48 inches. Photo courtesy of Krakow Witkin Gallery

With its anonymity and dry humor, Barry’s work achieves a transcendent vocabulary of its own, though it can be appropriated. We are drawn to the word “Intimate” in Barry’s Untitled (2021) and reminded of ads for the fashion conglomerate Calvin Klein and any number of pared down, cheeky corporate marketing campaigns. (Hard to know who got there first, considering Barry’s similarly stripped-down works on paper from the ’70s.) Barry’s “Intimate” appears upside down, slanting to the left and cut off at the end by a thin, nearly imperceptible graphite line. Adjacent words like “Relieve” are slashed in half by the same illusion of a frame, while the “C” in “Conflict” is mostly imagined or invoked. We are asked to fill in the blanks, using not only the absent letters or parts of letters but the complex, sometimes contradictory aspects of lived experience they draw on.

Like Scrabble pieces strewn across a table, Barry’s fragmented texts inspire us to think. Such thoughts, however, will never end in us “knowing” anything. Just try to figure out a way through Untitled (2022) or even INCOMPLETE (2021) — you will know no more than you did before. But you have been thinking the whole time, which is Barry’s larger point: the purpose of the artist is to “create a situation.” The moves and decisions he makes open up space for artist and viewer alike. Perhaps the game is more akin to chess; a painting Barry completed while still in graduate school resembles an empty chessboard.

Rooted in his own education as well as volunteer work, Puryear’s ongoing investigation of material culture and craft traditions is also a search for social justice. Puryear takes apart the things that, for him and others, signify the promise of liberation, such as Phrygian caps or beggar’s bowls, as well as signs of the structures of oppression that too often defeat it. He turns the pieces over, in his mind and in his hands, to create art that meditates on the universal as well as the personal struggle for equality.

Martin Puryear exhibition view. Photo courtesy of Krakow Witkin Gallery

However accomplished their work has become, then, both artists continue to draw attention to process. This holds the key to their perpetual self-development, as they share with us what they have learned. Only by attention to process — to the elements of practice — can we “think about what we are going to do” (in the words of one of Barry’s early works). Together, Barry and Puryear share an interest in time: the time of a thought, the time craft takes. In a sense, they are making more time for themselves. At the Krakow Witkin Gallery, we are fortunate to join living legends as they drink from the fountain of youth.

Helen Miller is an artist. She teaches at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design and Harvard Summer School. Michael Strand is a professor in Sociology at Brandeis University.