Arts Commentary: The Goldsmith-Warhol Copyright Decision — Reason to be Concerned

By Steve Provizer

Decisions like these are increasingly troublesome because they will dictate what constitutes”fair use” for decades to come, even as technology evolves in threatening ways.

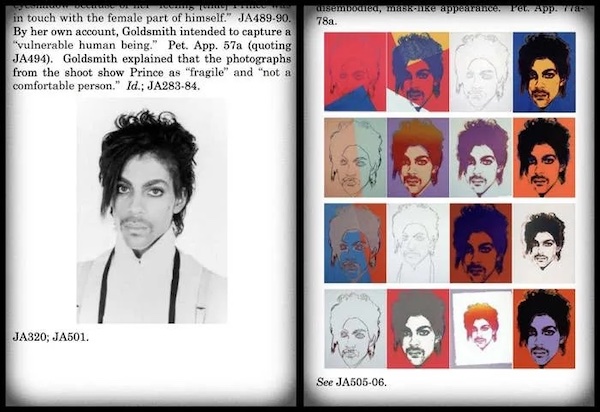

Left: A portrait of Prince taken by photographer Lynn Goldsmith in 1981. Right: A series of silkscreen prints Andy Warhol later created using the photograph as a reference are seen in documents filed with the Supreme Court. Photo: Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Last October, I laid out the facts of this litigation here. On May 15, in a 7 to 2 vote, the Supreme Court ruled that photographer Lynn Goldsmith was entitled to copyright protection and that Andy Warhol was not entitled to use her photo of Prince without being paid and acknowledged. At the center of the case is the concept of “fair use.”

The court majority focused on a couple of parameters in deciding whether fair use was applicable. One was that both Warhol and Goldsmith were competitors in the business of licensing material to magazines. Warhol’s work might have been acceptable as fair use if it qualified as “transformative use.” But Warhol made only a “modest alteration” to the original so the image couldn’t claim that status. The second and related element, as per Justice Sotomayor, who wrote the decision, was that fair use should be evaluated as to: “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes.”

Justice Elena Kagan and Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. dissented. Kagan argued that the decision “will stifle creativity of every sort…It will thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge. It will make our world poorer.”

Supreme Court decisions often demonstrate a certain detachment, but in this case there was an unusually combative tone to the comments. Dissenters cast the majority as near-Philistines while the majority cast the minority as poseurs.

Kagan wrote: “The majority does not see it…And I mean that literally. There is precious little evidence in today’s opinion that the majority has actually looked at these images, much less that it has engaged with expert views of their aesthetics and meaning.” She made the point that an editor, presented with Goldsmith’s photo and Warhol’s portrait, would have a clear choice to make. But from the majority’s perspective the editor might as well flip a coin. She posits that the majority’s decision rests solely on the fact that both images were licensed to magazines.

Sotomayor wrote that Kagan’s opinion was made up of

… a series of misstatements and exaggerations, from the dissent’s very first sentence to its very last…Warhol himself paid to license photographs for some of his artistic renditions…Such licenses, for photographs or derivatives of them, are how photographers like Goldsmith make a living. They provide an economic incentive to create original works, which is the goal of copyright.

Sorting these issues out, as I wrote when I first covered this case, is not simple. The comments from both sides betray a bravado that betrays an understandable lack of confidence in their position. The truth is, it would be equally difficult to sort out the motivations of the litigants or any artists, for that matter.The editor decided to use Warhol’s print of Prince in order to sell copies of the magazine. Warhol’s motivation in making images of the Campbell soup cans? Who knows? Art makers rarely sit on the extreme ends of the spectrum — producing work with no thought of income or with the sole motivation of making money. Most creatives fall somewhere in between.

What is indisputable at this point: the duration of copyrights has run amok. And decisions like these are increasingly troublesome because they will dictate what constitutes”fair use” for decades to come, even as technology evolves in threatening ways. For example, the absorptive power of AI can suck up copyright images and then spit out amalgamated “originals.” Today’s Supreme Court is shaping the future of art and artists. We have reason to be concerned.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

This was a pretty straightforward ruling so far as I can see. International copyright law says that the original creator owns the rights to all derivative works, without exception, as long as the copyright lasts. In this case, there was no question that the photographer created the original work so there is no question that Warhol, as the creator of the derivative work, should have asked permission to use it and should have paid royalties if it was granted. Fair use clearly does not apply in this instance and never has so the Supreme Court did not set any Fair Use precedents in its decision, just confirmed what has been law as long as the copyright. I’m surprised that the ruling was even controversial but copyright law is often poorly known and understood, even, evidently, by some Supreme Court justices.

The law is bound by international treaty. It does restrict creativity. That’s part of the point. The other side of this are the thousands of artists and musicians, many of them of color, who have had their work appropriated by others who earn far more from their creation than they did.

I have been repeatedly surprised, however, that the very long copyright terms now in place do not violate the “limited times” clause in the Constitution but the courts have just as repeatedly upheld them.