Arts Commentary: The Power and Perils of Copyright– Andy Warhol, Lynn Goldsmith, and the Prince Print

By Steve Provizer

Whatever the Supreme Court determines will alter the world of artists, writers, and musicians for decades to come, a world that has already been dealt a financial blow by the economic pressures of the internet.

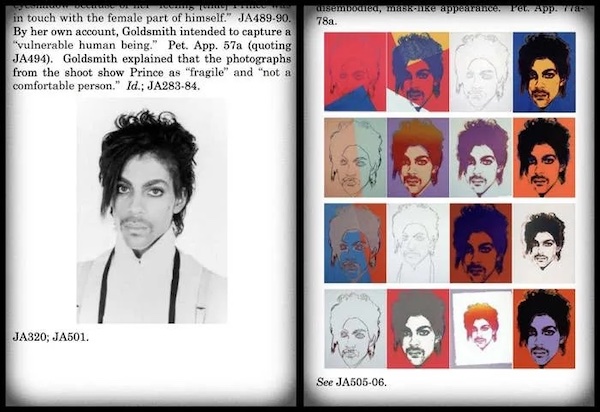

Left: A portrait of Prince taken by photographer Lynn Goldsmith in 1981. Right: A series of silkscreen prints Andy Warhol later created using the photograph as a reference are seen in documents filed with the Supreme Court. Photo: Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States.

A copyright case involving Andy Warhol, Lynn Goldsmith and an image of Prince arrived at the Supreme Court on October 12. The case is worth our attention.

In 1981, photographer Lynn Goldsmith took a black and white photo of the musician Prince. Three years later, Vanity Fair paid Goldsmith a $400 licensing fee so that Andy Warhol could use the photo as an “artist’s reference” to create an image for the magazine (No available data on what they paid him). They published that image in 1984. In the meantime, Warhol had created 16 silkscreens, screen prints, and sketches based on Goldsmith’s image. In 1987, Warhol died, and the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (AWF) took over control of the copyrights. In 2016, after Prince’s death, Vanity Fair’s parent company, Conde Nast, paid the foundation $10,250 to run another image from Warhol’s Prince Series on the magazine’s cover. Goldsmith didn’t receive payment or credit and took the foundation to court over copyright infringement.

In 2019, Federal judge John G. Koeltl ruled that Warhol had transformed Goldsmith’s original photograph under fair use. The portrait changed the image of Prince “from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure.” (Sounds as if the judge was an art curator in his spare time.) In any case, in 2021, the 2nd US Circuit Court of Appeals upheld Goldsmith’s claim. They decided that Warhol’s image wasn’t “transformative” — it was “derivative” because it bore too much of a resemblance to Goldsmith’s photo to qualify as “fair use.” The court found that the primary market for the Warhol work and Goldsmith’s photograph were different, concluding that retail sales of the Prince Series might not constitute an infringement of Goldsmith’s copyright. However, the court ruled that “AWF’s licensing the Prince Series works to Conde Nast [in 2016] without crediting or paying Goldsmith” did usurp a market in which Goldsmith’s photograph competes.

Of course, deciding copyright questions on the basis of market criteria doesn’t address the fundamental question: What makes a work derivative as opposed to transformative? The reality is that art forms rely on earlier work in order to evolve, but acknowledging this only further begs the question.

Can we gain perspective by looking at copyright in jazz? Yes, there are congruities, but drawing parallels is a complex matter. Some jazz improvisations are fresh and creative, cut nearly from whole cloth. Many are, to some degree, an amalgam of previous solos by the improviser and by other musicians and some solos are codified — recreated over and over again. Charles Mingus once commented: “If Charlie Parker were a gunslinger, there’d be a whole lot of dead copycats.” Copyright law has determined that jazz improvisations are not covered by copyright. The law considers this derivative material, and that means that jazz musicians don’t receive protection from bootleg recordings. Only copyright holders can sue bootleggers. I will point out that there’s a considerable difference between Warhol using a well-known photo of a famous person as a template for his work and a musician learning Bird licks in the woodshed.

Whatever the court determines will alter the world of artists, writers, and musicians for decades to come, a world that has already been dealt a financial blow by the economic pressures of the internet. A decision in favor of Warhol would further erode what has become a shaky bottom line. Yet a victory for Goldsmith could curtail creative freedom to build on work of the past because of the fear of copyright infringement suits.

There are no simple answers, but the continuous extension of copyright terms — 11 times in the last 40 years — lurks menacingly in the background. An artist or musician in the ’20s would have to wait 56 years before being free to use a work whose copyright had been renewed. In the late ’70s, this interlude increased to 75 years — or the life of the author plus 50 years. In the 2000’s, this period was extended to the life-of-the-author plus 70 years. In the case of a work-for-hire it is now 95 years from the date of first publication or 125 years from creation, whichever comes first. The drift is clear: those on the top will stay there longer while the rest struggle.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Tagged: Andy-Warhol, copyright, improvization, Lynn Goldsmith, Prince