Visual Art/Design Book Review: “America Goes Modern” — The Triumph of the Beautiful and the Functional

By Mark Favermann

America Goes Modern does splendid justice to the genesis of a miraculous design phenomenon.

America Goes Modern: The Rise of the Industrial Designer by Nonie Gadsden with Kate Lanford Joy. Published by MFA Publications, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, 190 pages, 110 Color illustrations, 2022.

“Object poetry” is a term for looking at physical objects from a lyrical perspective. It comes from the German word dinggedicht — “thing poem,” a literary genre that is about making the mundane magnificent, the practical elegant enough to be worthy of grace. At its best, this artistic approach calls for a fresh look at what seems to be an ordinary thing, or it may transform an extraordinary object into something familiar.

“Object poetry” is a term for looking at physical objects from a lyrical perspective. It comes from the German word dinggedicht — “thing poem,” a literary genre that is about making the mundane magnificent, the practical elegant enough to be worthy of grace. At its best, this artistic approach calls for a fresh look at what seems to be an ordinary thing, or it may transform an extraordinary object into something familiar.

Katharine Lane Weems Senior Curator of Decorative Arts and Sculpture at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Nonie Gadsden powerfully celebrates visual “object poetry” in her wonderfully illustrated and narrated new book, America Goes Modern. The volume is not only filled with scholarly writing, but viscerally embraces, even exalts, objects that are both beautiful and functional.

Roughly set between the two World Wars, with a focus on the ’20s and ’30s, this study looks at pioneer American industrial designers through several of their masterpieces in the MFA’s American Decorative Arts collection. Gadsden and Kate Lanford Joy examine the efficacy of design, as interpreted by form, color, ornament, and materials. They tell a vibrant story of the creation of a distinctively modern American aesthetic. Gadsden analyzes how these seminal objects — visually, physically, and even spiritually — came to represent the hopes and ambitions of the Roaring ’20s and then the Depression Era ’30s. The result is a book that does justice to a very American, and rather miraculous, design phenomenon.

In a thoughtful introduction, Gadsden makes her case for Modernism, and then hones in on five wonderfully talented but quite different trailblazing industrial designers: Paul T. Frankl (1886-1958), Donald Deskey (1894-1989), Viktor Schreckengost (1906-2008), Harley J. Earl (1893-1969), and Belle Kogan (1902-2000). The author feels that each of these individuals created transformative works in the interwar years that mirrored the nation’s zeitgeist.

Gadsden draws on the extensive and often unequivocally beautiful collection of John P. Axelrod, an Overseer of the Museum Fine Arts Boston. She has studied this generous gift for nearly two decades and, in America Goes Modern, describes the rich cultural resonances of the various chosen objects. The author’s analysis superbly intertwines social and economic context, detailing the object’s contemporary value along with its connections to innovations in industrial design, as well as in manufacturing and merchandising. She dissects, superbly, the creative process of notable though not generally well-known designers.

The then burgeoning profession of industrial design attracted individuals from a variety of backgrounds. Among the roster of early industrial designers could be found painters, sculptors, architects, interior designers, window display designers, set designers, silversmiths, jewelers, metallurgists, fabricators, and even ceramicists. The synergy nurtured by these skills upturned traditional training, and that led to a flowering of creative genius, a fertile explosion of beauty and function.

Viktor Schreckengost, Punch bowl from the “Jazz Bowl” series; designed 1930, made 1930‑31.

Glazed porcelain with sgrafitto decoration. Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Paul Frankl came out of an architectural education in Berlin. But after arriving in the US he soon became more interested in painting along with crafting fine furniture. He also designed clocks and other decorative objects. Frankl was interested in forging an American Modern aesthetic, to the point that in the late ’20s he introduced his celebrated “Skyscraper Style.” After only a few years he left that format to focus on metal furnishings throughout the ’30s. His elegant products became an inspiration for the country’s design community.

After studying architecture at UC Berkeley, Donald Deskey took another path. He became a fine artist as well as a window display designer and an interior designer. An early major influence on his aesthetic imagination was a visit in 1925 to the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris. After returning, he established his design firm in New York City; that later would become Deskey-Vollmer, which specialized in furniture and textile design. His successful career was highly influential.

Paul T. Frankl, “Skyscraper” desk and bookcase, about 1927–28. Walnut, walnut veneer, pine, birch plywood, core board, American beech, steel, paint, silver-plated brass handles, electrical wiring and light bulb. Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

American automotive and transportation designer Harley Earl dropped out of Stanford University to work in his father’s custom car body shop in the early ’20s. From there he eventually went on to become the director of design for General Motors, the first top executive ever put in charge of that department in the history of major American corporations. Among the automotive design techniques he introduced: the use of free-form sketching and sculpted clay models. Additionally, he came up with the idea of “concept cars” as design and marketing tools.

Extremely long-lived, Viktor Schreckengost was one of the most prolific and eclectic of the first wave of Modernist industrial designers. This is not to say everything he designed was brilliant; many of his objects could, at best, be classified as kitsch. He designed everything from bicycles to radar to trucks to dinnerware to ceramics, but Schreckengost is best known for his seminal 1930 Jazz Bowl for Cowan Pottery, a large blue punch bowl whose very graphic decoration reflects the excitement of the Jazz Age and its nightlife.

Belle Kogan was one of the rare early woman industrial designers. Initially educated as an artist, she became a very skilled silversmith, jewelry-maker, and a designer of houseware products and other consumer items. Kogan had a wonderful way of articulating her mission; she strongly believed that “good design should keep the consumer happy and the manufacturer in the black.” She was one of the first industrial designers to work with plastics, coming up with celluloid toilet sets, clocks, toasters, and Bakelite jewelry. Most remarkable, Kogan set up her own design consultancy — something women rarely did at that time.

The Arts Fuse asked Nonie Gadsden a few questions about what she learned while researching America Goes Modern.

Arts Fuse: What surprised you the most from doing the book?

Nonie Gadsden: I was surprised by how much we could find online. Kate Joy and I researched and wrote much of this book during the depths of the pandemic, when libraries and archives were closed. The wealth of information out there is remarkable.

AF: How do you most succinctly define Modernism?

Gadsden: Now this is a hard one. People have spent careers trying to define Modernism. I offer this: Modern Design refers to a range of styles popular in the early to mid-20th century that both reflected and helped to shape the impact of the era’s cultural, technological, and industrial innovations on modern life.

AF: In researching the book, who was your favorite designer?

Gadsden: Belle Kogan, no question. It was so exciting to dive into the life and career of such a pioneer and to discover her deep — and early — knowledge in plastics.

Belle Kogan, Two‑tone bracelet, designed 1933–34. Bakelite (plastic). Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

AF: Who was the most difficult to capture or describe?

Gadsden: The most challenging chapter was the Nightlife chapter featuring Viktor Schreckengost and the Jazz Bowl. There are so many cultural associations with the Jazz Bowl — from Prohibition to Jazz and Jazz culture, to the advent of the larger urban nightlife scene, and more — that it took us a whole lot of time to find the right approach. Schreckengost himself has been so well studied that finding ways to offer something new about him was challenging as well.

AF: Beyond her feminist and pioneering aspects, what are the most compelling things about Belle Kogan’s designs?

Gadsden: Kogan made practical designs. Designs that were modern, but not outrageously so. Designs the average female consumer would feel comfortable with. Her interest in finding a happy middle ground, instead of the flashiest look, gave her designs an elegance and grace.

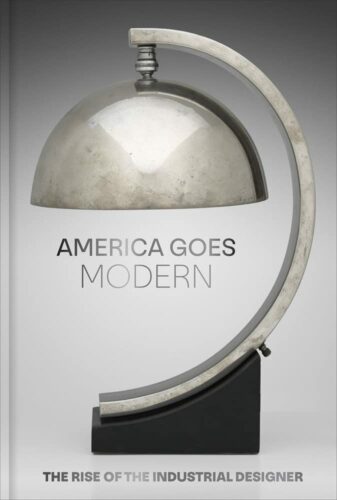

AF: Why did you choose as the book’s cover art Donald Deskey’s lamp?

Gadsden: I did not want to use, and thus privilege, one of the chapter’s featured objects. I also knew that those works would have multiple views within the book. Deskey’s dome-shaped lamp has such bold, clean lines, I thought it added a great graphic quality to the cover. In addition, as an electric table lamp made of chromium-plated metal, shaped with strong curves, it encapsulates many of the themes of the book.

Mark Favermann is an urban designer specializing in strategic placemaking, civic branding, streetscapes, and public art. An award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he is design consultant to the Massachusetts Downtown Initiative Program and, since 2002 has been a design consultant to the Boston Red Sox. Writing about urbanism, architecture, design and fine arts, Mark is contributing editor of the Arts Fuse.