Visual Arts Review: Zoya Cherkassky – An Immigrant Paints the Other Israel

By David D’Arcy

Her hope for Israel today, Zoya Cherkassky told me, is the evolution of a multi-racial society that she hopes will ensure its survival.

Zoya Cherkassky: The Arrival of Foreign Professionals at Fort Gansevoort, 5 Ninth Avenue New York, NY, through June 3.

The Arrival of Foreign Professionals (after Abram Cherkassky), Zoya Cherkassky, 2023

The images we tend to see of Israel today are of mass demonstrations against the recently-elected government’s maneuver to weaken the country’s Supreme Court. Other images are perennial — Israeli troops battling with Palestinians in the occupied West Bank. The US remains a steadfast supporter though it is trying to figure out just what that means now. To complicate matters, Saudi Arabia, which Israel called one of its newest friends in the shifting of allegiances in the Middle East, is finding a new friend in Iran, Israel’s dreaded enemy.

Zoya Cherkassky, 47, who lives and paints in Israel, is a shrewd and caustic observer of her adopted country. She doesn’t hold back in her paintings, which can be tender (her family), satirical (immigrants from ex-Soviet lands, whom she calls “new victims”), grotesque (the messy circumcision of an elderly uncle), and brazenly sexual (prostitutes serving their customers). Her images of the Israel that her family inhabits seems to picture everything that’s not in the news.

An insider and an outsider, Cherkassky was born in Ukraine and emigrated to Israel with her parents in 1991 at the age of 14. In the former Soviet Union, she would have been called a Jew. In Israel, she would be called a Russian, as most immigrants from the former Soviet Union are called. Cherkassky stressed in a conversation with me that she is not Jewish in Israel, since her mother’s heritage is mixed. She tried to convert, but says she failed the test. She is married to a Nigerian truck-driver (and frequent painting subject), Sunny Nnadi, who was undocumented and stuck in a stateless limbo until he got his papers recently. Hence her insider/outsider status and, up to now, an ongoing flow of comic glimpses of her adopted homeland and the country where she grew up. (Cherkassky tells stories like a stand-up comic. She talks at length about her life and her paintings with Gannit Ankori, director of the Rose Museum at Brandeis University, on the program Studio Israel / Jewish Arts Collaborative. The episode was recorded before the opening of her current show in New York.)

In her new show The Arrival of Foreign Professionals, she pivots away from satire. The exhibition is named after a 1932 painting by Cherkassky’s great grand-uncle, Abram Cherkassky (1886-1967), which she first saw in a museum in Kiev on a visit before the Russian invasion. The painting shows a Black couple visiting a Soviet family during the Stalinist time. There are smokestacks in the background. We don’t know if the factories are real or imagined, but they reflect Stalin’s ambition to industrialize the Soviet Union. To achieve that goal, the Soviets brought skilled specialists from anywhere they could get them, including technically trained Africans and African-Americans. Cherkassky’s scene of the encounter of Africans and Soviet citizens (in their own apartment, unlikely then for anyone but party cadres), fits all the requirements of Socialist Realism, including the theme of international brotherhood, which Stalin honored when it suited him.

The Arrival of Foreign Professionals, Abram Cherkassny, 1932

In homage to her great-uncle, Zoya Cherkassky produced her own version of that scene this year. Like the original on view, it’s more dutiful and naif than heroic, but it taps into a rare moment in Soviet history, assuming the visit in the picture actually occurred. Her depiction of the Black visitors has been seen, by some critics, as stereotypical. But every figure in the painting — and the very notion of copying the image — is a play on stereotypes. So is much of what Cherkassk has painted before, given the enormous influence comics has had on her style. When observing the former Soviet Union and Israel, that’s been her way of exploring — or just enjoying — uncomfortable truths.

Zoya Cherkassky addresses the same theme of foreign visitors in “Party in the Dorms” (2022), a scene from the ’80s where we see young women drinking and dancing with African men of their own age. The style of the painting draws more from comic books than from Soviet rulebooks or “internationalism.” When her show opened in New York, Cherkassky told me that the scene in this picture is inspired by a time when Africans studied at Soviet universities. Young women who felt stuck in the USSR were eager to meet anyone new. The women in the picture – drinking, dancing, and embracing the foreigners – were girls of modest backgrounds. For this occasion they were wearing the best clothes they had, which often meant garish combinations of anything that looked like it came from the West. garb perfect for satire. The young men tended to be from elite, politically-connected families in developing countries that were aligned with Moscow. These were the days just before perestroika, a time when style, free association, and sex crawled into view. The scene is more realistic than ham-fistedly socialist, though there are the same polluting smokestacks in the background

“My Family at the Immigration Office,'” Zoya Cherkassky 2023

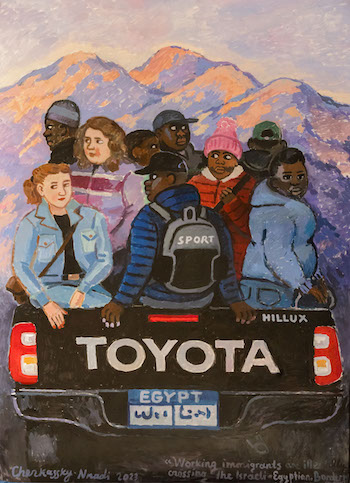

Closer to her adopted home, “Working Immigrants are illegally crossing the Israeli-Egyptian Border” (2023) depicts Africans and East European women packed into the back of a pickup truck. The snow-capped peaks and clear blue sky in the background suggest ‘Marlboro Country,’ though the figures seem to be borrowed from R. Crumb — until you understand the poignancy of the image. The truck is heading toward the Sinai, where passengers (like her husband) paid gangs to smuggle them into Israel. A fence stands in the way there now. Many of the European women who entered there were sex-trafficked. Look closely, and the scene resembles time-tested images from the late 19th century of immigrants huddled on the deck of a boat, or of refugees today headed for Europe. Bear in mind that groups on Israel’s ideological right periodically call for deporting the undocumented en masse.

The New York show represents an artistic pivot point for Cherkassky. The painting style here recalls her earlier work, minus the satire and humor. She often set those paintings in or around apartment blocks that surrounded Soviet cities — drab skies and clothing, bullying by local gangs. But there were also scenes of fun among friends, including one in a girls’ bathroom with an open squat “Russian” toilet.

Working Immigrants are illegally crossing the Israeli-Egyptian Border, Zoya Cherkassky, 2023

Cherkassky met her undocumented husband when she asked him to model for her. My Family at the Immigration Office, painted this year, shows the uneasy couple with their young daughter under a display of Israeli flags, waiting for the documents that took her husband seven years to get. The family looks anything but cheerful.

“I would agree to use a Soviet toilet until the end of my life if I could forget this experience with the Israeli [Ministry of the] Interior,” she tells Gannit Ankori of Brandeis in their interview.

As soon as she got off an EL Al plane, Cherkassky built her reputation in Israel by envisioning trouble in what was promised to be utopia. She and her unreligious parents immediately felt a cultural jolt, particularly the pressure to abide by religious rules, whether it was an inspection of their home by a rabbi or a circumcision performed on her Uncle Yasha by a distracted Hasidic doctor. Images like that, some just as raunchier, headlined her 2018 show Pravda at the Israel Museum, the most established art institution in Israel. Visitors laughed. Critics praised her irreverence and accuracy. Collectors vied for her work. Those who would have objected stayed away.

Her hope for Israel today, Cherkassky told me, is the evolution of a multi-racial society that she hopes will ensure its survival. The creation of such a society would make her family’s wait at the immigration office seem short.

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including The Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

Tagged: Fort Gansevoort, israeli art, The Arrival of Foreign Professionals