Visual Arts/Book Review: “Fellow Wanderer: Isabella Stewart Gardner’s Travel Albums” — Upper Class Gilded Age Tourism

By Peter Walsh

Faced with the dual dilemmas of the opacity of the albums themselves and the now painfully obvious narrative of colonialism, wealth, and white privilege, some of Fellow Wanderer’s authors dodge into more easily researched side issues, including information about the many photographs Isabella Stewart Gardner collected on her travels.

Fellow Wanderer: Isabella Stewart Gardner’s Travel Albums edited by Diana Seave Greenwald and Casey Riley. Princeton University Press, 244 pages, $55

Currently at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum’s Fenway Gallery through May 9: Fellow Wanderer: Isabella’s Travel Albums.

The Gardner Museum’s lavishly produced, larger-than-coffee-table-sized volume on its founder’s extensive travels begins with a deliberate anachronism. A two-page map documents Gardner’s travels recorded in her albums, but it does not show the world as it was at the time the albums were assembled (1867-1897), but with 2023 political borders. “Mapping Gardner’s travels is complicated for several reasons,” the book’s editors, Diana Seave Greenwald and Casey Riley, write in a note. “Traveling at the height of imperialism and during a century where there were wars and shifting territorial control, maps were not stable during Gardner’s lifetime.… In addition, the concept of what constitutes a sovereign nation has changed.”

The Gardner Museum’s lavishly produced, larger-than-coffee-table-sized volume on its founder’s extensive travels begins with a deliberate anachronism. A two-page map documents Gardner’s travels recorded in her albums, but it does not show the world as it was at the time the albums were assembled (1867-1897), but with 2023 political borders. “Mapping Gardner’s travels is complicated for several reasons,” the book’s editors, Diana Seave Greenwald and Casey Riley, write in a note. “Traveling at the height of imperialism and during a century where there were wars and shifting territorial control, maps were not stable during Gardner’s lifetime.… In addition, the concept of what constitutes a sovereign nation has changed.”

A glance at current headlines might suggest that these issues may have only intensified. Nevertheless, the editors explain that “[w]e have used current twenty-first-century borders to define which countries Gardner visited. While not a perfect solution, we think it will help readers grasp the scope of her journeys.”

The problem with this approach is that the perspective readers grasp is likely to be in a 21st-century frame, one familiar to modern tourists. This is far from helping them to appreciate the range of voyages Gardner made as a wealthy, highly privileged woman in the late 19th century. Imagine the same map without the contemporary borders and you can see a very specific kind of traveling, one that the book tends to obscure.

The Gardners (Isabel and Jack) traveled at the point in which Western imperialism had reached its high noon. Outside of North America, almost all the places she visited were, at the time, either European nations or parts of European colonial empires. Turkey, Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, and, more nominally, Egypt and Sudan were all part of the Ottoman Empire, a major European power before the First World War. Indonesia was Dutch territory, Cambodia and Vietnam were controlled by the French, Cuba was, for the time being, still part of the much-diminished Spanish empire in the New World, and the British ruled over India, Pakistan, Myanmar, and Singapore, and, increasingly, Egypt. “Austria,” which Gardner visited four times between 1867 and 1894, was then a name for the sprawling, multinational Austro-Hungarian Empire. Even Norway, when Gardner visited it in 1867, was a possession of Sweden.

The two exceptions to these European-controlled territories were both in East Asia: China and Japan, ancient empires in their own right. Japan, recently “opened” to the West by the United States, was rapidly modernizing under a Western industrial-colonial model. Coerced, sometimes by force, into trading with Western merchants, both nations already had significant populations of resident Europeans and Americans.

In China, the Gardners never ventured far from the coast. Of the seven cities they visited there, two (Hong Kong and Macau) were European colonies (of Britain and Portugal respectively) and two more (Canton and Shanghai) were treaty ports established after China’s humiliating defeats in the Opium Wars. Canton (Gardner used the English name for the city; Fellow Wanderer uses the modern name: Guangzhou) had a long association as the Asian end of the “China Trade” that had helped create the Gardner and Stewart family fortunes. Isabella found Shanghai, with its concession districts for French, British, and American settlements, “too European for local color.”

At the same time, the Gardners, as extensive as their travel was, skipped over independent and culturally significant states nearby, including Siam, Nepal, Persia, and Abyssinia. They also avoided the whole of South America, where revolutions had thrown off Spanish and Portuguese colonial rule decades earlier; sub-Saharan Africa; Australia; and Oceania.

So why did Isabella so restrict herself to territories firmly under the control of European colonial powers or already well known to Westerners? She never says explicitly, but likely priorities included comfort, convenience, and safety. Colonized countries had established transportation networks and tourist routes, useful consular staff, Western style accommodations, and, if a particular side trip seemed a bit more risky than usual, colonial troops or diplomatic staff as escorts. Friends, allies, and social peers, based in local businesses or the colonial bureaucracy, smoothed the way. These arrangements meant that Isabella never had to leave her comfortable bubble of wealth and privilege.

Visiting notable sites around Canton, center of some recent antiforeigner riots, the Gardners were escorted by the American consul under the protection of staff members from the largest American trading enterprise in China, Russell & Company. In Shanghai, they stayed at the residence of another American merchant and his wife and then at the American legation. Their base in Hong Kong was the grand Rose Hill estate built by the Russell & Company partner Warren Delano Jr., maternal grandfather of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who had built his first fortune by smuggling illegal opium into China. In Hong Kong, Isabella joined shopping trips and dinners organized by Delano’s daughters. She and her husband also enjoyed an informal lunch at Government House, the stately official residence of the colonial governor, Sir George Bowen, who later took them out in his steam launch.

Isabella Stewart Gardner and Jack Gardner at a lunch party in Seville, Spain. From Isabella Stewart Gardner’s Travel Album: Spain and Portugal, Volume II, 1888, page 13.

This sort of thing went on month after month. In Cambodia, the Gardners traveled to the famous temple complex of Angkor Wat with the help of French colonial forces, there apparently to dine “amid the ruins” on elegant French cuisine accompanied by wines and champagne. In Japan, the Gardners socialized with Bostonian William Sturgis Bigelow, a major collector of Japanese art and MFA patron, rich enough not only to fund his years-long collecting sojourn in Japan but to subsidize other Boston scholar-collectors there as well.

Even in the furthest reaches of her Nile voyage, on an Egypt trip mentioned only in passing in Fellow Wanderer, Isabella is following in the footsteps of wealthy Boston friends. At the southernmost point in their trip, the Second Cataract and Rock of Abusir, she “hunted amongst the carved names for those of friends and found several, as well as the historical ones. Whilst [Jack] was busy scratching ‘Gardner’ I had the top of the mountain all to myself.”

Easy as it is to romanticize this sort of travel from its picturesque moments, upper-class Gilded Age tourism, possibly aside from the long ocean voyages, would probably not appeal to most modern Americans, who are used to traveling far less formally. Isabella’s sort of travel, steeped in conspicuous consumption and status, not only involved huge sums of money and months of dedicated time, it required elaborate planning, intricate social introductions, complicated arrangements for suitable transportation and accommodations, numerous servants and local guides, lavish luncheons, and, night after night, long formal dinners with their hosts of the evening. This was not carefree backpacking. Hauling around huge steamer trunks stuffed with the heavy, complicated, constrictive Victorian costumes needed for several changes a day throughout the trip was part of the standard experience.

Edith Wharton’s roughly contemporary grand progress through Europe, described in more detail than Gardner’s, involved long, touristic days in a chauffeur-driven car, visits to ruins, gardens, and villas, servants sent ahead to prepare the hotel staff and to draw baths, and massive extravagance at every turn. Wharton’s trips, far less wide-ranging than Gardner’s, exhausted even her close friend Henry James, who was no stranger to elite socializing. (It may be worth noting that high-status travel for Anglophone males at the time was more or less the opposite of this; compare, for example, the self-consciously dangerous and physically challenging — and ultimately near fatal — adventure expeditions of Theodore Roosevelt.)

Fellow Wanderer catalogues 28 travel albums but details Isabella’s travels much more selectively, with essays by different authors for Spain, India, China, Japan, and the western United States. In their introduction, Greenwald and Riley try to frame the albums as “the most important and understudied archives of [Isabella’s] experiences, relationships, and ambitions.… Because they were assembled in concert with her traveling, Gardner’s albums represent her immediate responses to a range of world cultures, training her for the collection and arrangement of the disparate works she would eventually display in her eponymous museum.”

Nevertheless, they acknowledge that intensive travel and collecting belong to two different phases of Isabella’s life: “She collected very few works of fine art while traveling abroad between 1867 and 1897.” What she did bring home were mostly standard tourist mementos: “fans in Spain, opium bottles in China,” and bottles of sand from Egypt.

Isabella’s serious art collecting didn’t begin until after 1891, when the death of her father left her the funds to compete with millionaires like J.P. Morgan and Henry Clay Frick in the most elite reaches of the world art market. The exceptional works she pursued couldn’t be bought on the fly; they typically required months of delicate negotiations with European owners through intermediaries like Bernard Berenson and sometimes with foreign governments, who were increasingly restricting the kinds of art that could leave their borders. As plans for a museum matured, she shed other properties and expenses to concentrate on her life’s monument.

Isabella Stewart Gardner, Travel Album: India, Pakistan, Yemen, and Egypt, Volume VI, page 38, 1884.

Aside from some European trips before her marriage, Isabella’s travels were precipitated by two personal crises: first to recover from the early death of her only child, and then, some years later, to escape swirling rumors about her close relationship with a much younger man. Like so much of her biography, though, Isabella’s travel albums are oddly impersonal. They sometimes include her own watercolors, pressed flowers and plants, or bits of print picked up along the way, but most of the album real estate is devoted to commercially produced tourist photographs she bought in local studios along the way.

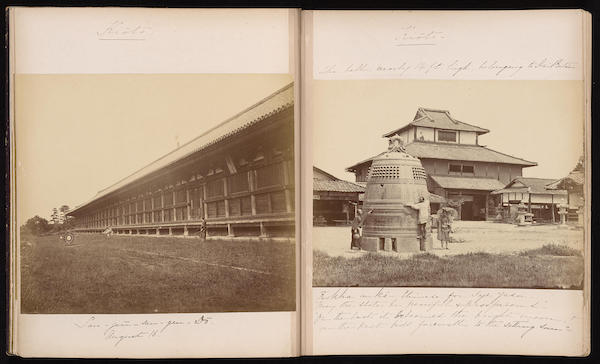

Gardner traveled before the age of the snapshot, when photographic equipment was bulky, complicated, and expensive, and exposing and developing images was tricky and messy and required a certain level of professional skill. The tourist studios that European and American photographers set up in cities across Europe, the Middle East, and Asia provided the tourist trade with hundreds of ready-made visual records. These standard images are primarily what Isabella decided to use to document her travels, adding only brief notes about places visited, arrival and departure times, and occasional notations about social engagements. There are no extended commentaries on what she saw or felt. Although many tourists supplemented the studio photographs with images of themselves taken by professionals hired for the purpose, Isabella added them only rarely, along with a few made by her husband.

Faced with the dual dilemmas of the opacity of the albums themselves and the now painfully obvious narrative of colonialism, wealth, and white privilege, some of Fellow Wanderer’s authors dodge into more easily researched side issues, including information about the many photographs Gardner collected on her travels.

David Odo, a scholar of 19th-century photographs of Japan, attacks the conundrum more directly in his essay, “Deceptive Intimacy: Isabella Stewart Gardner’s 1883 Japan Travel Albums,”

“In her travel albums,” Odo writes, “Gardner achieved a personal documentary style that is deceptively intimate, seemingly allowing viewers to travel along as she made her way but without revealing anything of her inner world.” Initially attracted by this apparent intimacy, Odo later changed his mind: “Now it seems to me that although we learn details such as where she stayed, with whom she lunched and when, Gardner’s notes communicate little if anything of her thoughts and emotions. Instead her notes seem to have arisen out of an impulse to document and record facts about her time in Japan, but little else.”

Odo goes on to describe the development of Western tourism in Japan, noting that by the time the Gardners arrived in the 1880s, “the tourist trail … was firmly established … as the country became a favorite destination for Western travelers.” The photographs acquired by Isabella and other Western travelers, which had roots in Japanese woodblock prints of popular tourist spots, “amplified the stereotyping effect of the tourist gaze rather than merely transliterating print to photograph.… [They] seemed to provide visual evidence to Western viewers that what they were seeing represented facts of Japanese life.”

Isabella Stewart Gardner, Travel Album: Japan and China, Volume II, 1883. Collected photographs, pen and ink annotations, pages 13–14

The concluding essay, Jaclyn M. Roessel’s “Southwest Invention,” goes further in the same direction. “The agenda of settler colonialism is to destroy the existing cultures and societies present in a place for the goal of creating a new society.… What we see in Gardner’s travel albums [of the American southwest] is a lack of inquiry.… We see the arrangements of the pages and some script identifying place but nothing regarding interactions, names, or personal thoughts.”

“What I think the images collected by Gardner lack,” she concludes, “is an awareness of what it means to be in a right relationship with a place, a people, and a culture.”

As a public figure, Isabella Stewart Gardner wanted to be noticed but not known. She hid her possibly transgressive private life and personal opinions behind a sphinx facade of conspicuous eccentricity. The passage of time and change in public values have altered the social context of Gardner’s travel albums. They seem to say so little, yet they now reveal that her attitudes toward race, privilege, colonialism, and entitlement were completely typical of her time and class. It’s hard to imagine that she would be pleased.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in scholarly anthologies and has lectured at MIT, in New York, Milan, London, Los Angeles and many other venues. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than 100 projects, including theater, national television, and award-winning films. He is completing a novel set in the 1960s.

Thanks for alerting us to the existence of this book and for highlighting the issues that it raises, explicitly or not. I’m going to find a copy in a public library right now and read it and think about all the ramifications that the reviewer has raised.