Classical Concert Review: Earl Lee Conducts The Boston Symphony Orchestra

By Aaron Keebaugh

Earl Lee, the BSO’s assistant conductor, pulled off a memorable debut. Let’s have him back in the subscription series again, and soon.

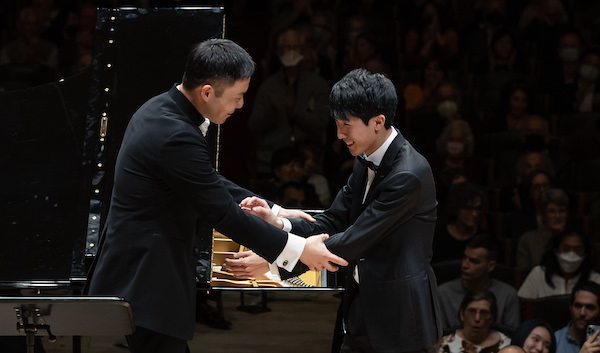

Assistant conductor Earl Lee, pianist Eric Lu, and the Boston Symphony Orchestra at Symphony Hall. Photo: Winslow Townson.

The first rule of conducting: don’t upstage the boss.

But as assistant conductor Earl Lee led the Boston Symphony Orchestra through mostly standard fare Friday afternoon, it became abundantly clear that he possesses the probing interpretive vision of any seasoned veteran.

Leading with bold and precise gestures, Lee walked the wire between grace and urgency in music by Mozart, Unsuk Chin, and Robert Schumann in his subscription series debut.

Since being named assistant conductor in 2021, Lee’s star has continued to climb. He won the Sir George Solti conducting award in 2022 and was named music director of the Ann Arbor Symphony prior to this season. In addition, he continues to fill orchestra podiums around the country as a guest conductor. And, while Friday’s program may have been a safe bet, it offered an opportunity for him to display his intriguing grasp of both poetry and flair.

Conductors are usually resigned to a supportive role in concertos. Yet Lee was an equal presence with guest soloist Eric Lu in Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor.

With its dark lyricism and wide dynamic shading, this music is often performed as if it were a romantic showpiece.

But Lu and Lee teamed up for a delightfully understated reading, where tension roiled beneath the surface. Lu’s elegant flourishes ebbed and flowed in all the right places. His tone flowered over the soft bed of sound Lee cultivated from the orchestra.

This was a performance in which neither pianist nor conductor overshadowed the other. Both traded the tempo changes and shifts in texture in perfect tandem. Lu explored both storm and stress in outer-movement cadenzas by Beethoven, while Lee placed the tuttis and accents with pinpoint accuracy.

The famous Romanza floated like an aria under Lu’s fingers, and the pianist and Lee found a complementary air of freedom during the subtle rubato. If the strings couldn’t always match Lu’s rhythmic precision in the Rondo, the music still generated sufficient drive and vitality.

The audience rewarded this superb joint effort with rapturous applause. Lu answered with a svelte and gently rollicking encore of Chopin’s Waltz in C-sharp minor, Op. 64, No. 2.

The concert opened with Unsuk Chin’s subito con forza.

Written in 2020 for the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth, this score unfolds in five minutes of nervous energy. The composer treats gesture and texture as the inspiration for a wild playfulness.

There’s plenty of Beethoven too. Woven between the stinging dissonances and agitated lines are references to the Emperor Concerto and the Fifth and Ninth Symphonies.

But the style is all Chin’s own, with a powerful momentum that never quite settles. Lee worked like a painter, layering the jagged musical shapes from each section into a colorful collage.

Earl Lee conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Photo: Winslow Townson

The conductor also realized the varied beauties of Schumann’s Symphony No. 2, which came after intermission.

Schumann drew upon past and present for this Symphony in C, reflecting the percolating zeal of Schubert and the evergreen teleological thrust of Beethoven.

Lee raptly conveyed that natural momentum while keeping a firm focus on the passing lyricism. The opening chorale sounded dark and distant against the soft strings. The intricate voicings of the Allegro moved with pleasing vigor.

Details aplenty were drawn out of the orchestra. The Scherzo displayed the ensemble’s piquant woodwinds and serene strings to good advantage in its respective trios. The finale coursed with verve from all forces.

But the gem of this setting was the Adagio, which Lee expressed through lush, vocal-style shapes. The shadow of Bach can be felt here as well, and he wove the fugue into a supple web of sound. Radiant yet intimate, the performance made for a memorable debut. Let’s have Lee back again, and soon.

Aaron Keebaugh has been a classical music critic in Boston since 2012. His work has been featured in the Musical Times, Corymbus, Boston Classical Review, Early Music America, and BBC Radio 3. A musicologist, he teaches at North Shore Community College in both Danvers and Lynn.

Tagged: Aaron Keebaugh, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Earl Lee

Wonderful review! Aaron Keebaugh’s precise and evocative wordings help me “hear” what he heard in Symphony Hall that night. Reminds me of my own years in Boston, hearing the orchestra under Steinberg, Leinsdorf, Ozawa, a young Michael Tilson Thomas–and, at Tanglewood, Leonard Bernstein,

The review also makes me want to get to know some works by Unsuk Chin. Always glad to learn of effective and communicative new (or newish) pieces! There’s lots of vitality in the classical-music world (as I try to point out in some of my own reviews for The Arts Fuse).