Book Review: “Look at the Lights, My Love” — Meditations in a Superstore

By Pat Reber

Can Nobel laureate Annie Ernaux lend literary dignity to a big-box store?

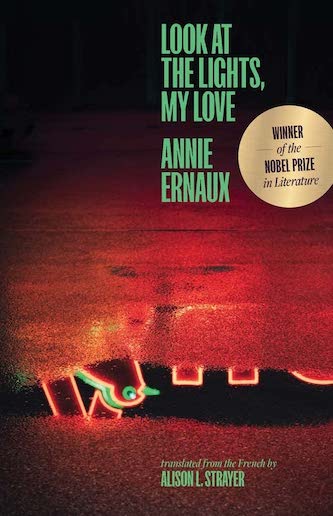

Look at the Lights, My Love by Annie Ernaux. Translated from the French by Alison L. Strayer. Yale University Press, 96 pages $16.

When you first see the title of Annie Ernaux’s newest book in English – Look at the Lights, My Love – the last thing you expect of this 2022 Nobel Literature Laureate is a year-long journal of her visits to a shopping mall in the north-west suburbs of Paris.

When you first see the title of Annie Ernaux’s newest book in English – Look at the Lights, My Love – the last thing you expect of this 2022 Nobel Literature Laureate is a year-long journal of her visits to a shopping mall in the north-west suburbs of Paris.

But this French writer’s ability to mine her everyday experiences for broader sociological, cultural and in this case economic significance comes through in nearly every page of this slim volume, first published in France in 2014.

Ernaux, 82, has written more than a dozen books since the ’70s delving into the highly structured nature of French society and its social and cultural prejudices, where a woman like her from a working-class family in a small Normandy town is still regarded as a novelty for having achieved “intellectual gentrification,” as she calls it.

One could say most of her works are memoirs, and yet Ernaux is often an abstract “we” or “she” in her writing. Her books have focused on abortion, middle age love affairs, divorce, her first awful sexual experiences, bulimia, raising her family, among other themes. She has been called the Simone de Beauvoir of her generation for the frankness and honesty with which she writes about women in the country’s life, society, and culture.

Why, then, would Annie Ernaux grab a shopping cart and head to the “superstore” in her favorite shopping mall – Trois-Fontaines – in the suburban town of Cergy for this book?

Her aim is to explore yet another realm of women that she says has gone largely ignored in French culture and literature.

“Superstores and supercenters continue to be extensions of the domain of women, of a domestic world that women keep in good working order by pacing through the aisles with mental lists of everything missing from the cupboards and the fridge …,” Ernaux writes.

Yet superstores have rarely appeared in published novels, largely written by bourgeois writers in Paris, Ernaux notes. She asks how much time might be required for superstores to “achieve literary dignity.”

In this search for “literary dignity” for the French equivalents of Target and Walmart, Ernaux takes the reader along as she shops the aisles, notes the store’s efforts at manipulating consumers with items priced one penny short of the next euro, and wonders what family could subsist on pork priced at 1 euro per person.

At first read, it’s not clear whether Look at the Lights achieves that dignity.

The Auchan superstore in the Trois-Fontaines mall is a cultural crucible, she writes, where “our unconscious minds are shaped;” where traditional gender roles in the toy aisles are perpetuated; where shoppers drawn by discount bins become clearly identifiable as economically needy; and where young men staff the electronics department with technical arrogance.

As critical as Ernaux is about all of this, she relishes the escape it provides from her writing and into the larger community. Going out to shop at the mall is a form of entertainment, she writes, in the way people in the old days would take walkabouts around town, to see what was going on. There is no other public or private space, she writes, “where so many individuals so different in terms of age, income, education, geographic and ethnic background, and personal style, move about and rub shoulders with each other.”

Seasonal festivities are heralded at the mall. On December 18, 2012, Ernaux approaches Trois-Fontaines with its holiday lights and garlands “hanging down like necklaces of precious stones.”

A young woman in front of her pushes a stroller with a little girl, looks up, smiles, and leans down toward the child.

“Look at the lights, my love,” the mother says to the child.

Annie Ernaux in 2017. Photo: Wiki Common

It’s nothing new for Ernaux to weave supermarkets into her writing. In one of her most seminal books, The Years, whose English translation was shortlisted for the 2019 Man Booker International Prize, supermarkets are part of the book’s head-spinning cultural rush from 1941 to 2006, from the time of her girlhood in the post-WWII “scarcity of everything” and the “time of the dead” to today’s affluence and terrorism. Supermarkets and the way family and friends flocked to them in the ’60s represented the country’s embrace of mass commercial development.

In some ways, the Trois-Fontaines mall and its Auchan superstore represent the culmination of that trend. Is it possible, Ernaux asks, that the time will come when today’s children, ever more accustomed to online shopping, will remember Saturday at the malls and superstores with the same sort of nostalgia people over 50 now remember “the pungent grocers’ shops of the past?”

For a reluctant box-store shopper like myself, this is hard to imagine. I still miss the butchers and bakers and cheese makers from my past life in city centers. At some point, Ernaux’s superstore journal became both overwhelming and tedious to me, and I almost stopped reading.

But there was something in Ernaux’s manner which kept me going. She concedes a sort of love-hate relationship with the superstore experience. She finds a “violence” in the controlling force of mass production, in “the colorful profusion of yogurt flavors,” in the reinforcement of social stigmas through the conspicuous accommodation of low-income shoppers. Yet she likes losing herself in “the crowd of shoppers and idlers.”

During Ernaux’s year of documented shopping, she records the Bangladesh factory disasters that killed 112 workers in November 2012 and 1,127 in May 2013. The victims were the poorly paid workers who produced 7-euro T shirts for the French, she writes, adding: “We who blithely reap the benefits of that slave labor cannot be counted on to change anything at all.”

The “extinction” of cashiers and clerks through the self-checkout line angers her. She writes about the “perversity” of this cost-cutting device, describing how the irritation that one used to feel standing in line behind a slow cashier is now aimed at a fellow customer fumbling with the machine.

Despite the long checkout lines, Ernaux relishes the opportunity for voyeurism. Here “we are closest to each other” and she can observe the standard of living, family structure, “eating habits, most private interests,” as someone else’s goods move along the conveyor belt.

Then the table turns. When another shopper recognizes her as the famous author and insists she go ahead in line, Ernaux hesitates. Of a sudden, she realizes her own shopping cart has become the “object” of observation – her bottles of champagne and wine, organic Emmental, crustless sandwich bread.

Trois-Fontaines in the suburban town of Cergy. Photo: Paul Grundy

Trapped like “rats” in a checkout line snaking through the cookie aisle, Ernaux wonders “Why don’t we revolt?” She toys with digging into the sweets and nibbling to avenge the store’s cost-cutting staff reductions.

She admires a new fashion in headscarves being worn by some women, noting how this commercial center has adapted to the cultural diversity of its shoppers to keep pace not just with Christmas and Easter but also with Ramadan.

Ernaux dismisses men who go through the store with cell phones pressed to their ears for help. She recalls a radio dialogue between two male journalists who joke about how their mothers still fill their refrigerators. “They laughed with satisfaction. At having remained, in some way, infants,” she recalls.

Women are the adults here and receive through this book visibility for the “subsistence” they labor to take home. It is their business to check each item to see if they can afford it.

Whether or not superstores achieve “literary dignity” through this book is another question. But the women she portrays and the children they shepherd past all the temptations reminded me of my own travails of shopping with children, so women do achieve this status through her book.

Would English readers have had an English translation of Look at the Lights had Ernaux not joined the elite circle of Nobel laureates?

Her translation history answers “yes.”

All but six of her 23 books have been translated into English, sometimes with a lag of decades, other times much less. Happening, about her illegal abortion in France in 1963, appeared in France in 2000 and reached English readers a year later. (Arts Fuse review) They are variously published by universities (Nebraska and Yale) or Seven Stories Press – a New York-based publisher she helped found in 1995 along with Octavia Butler and other writers.

Translator Alison L. Strayer. Photo Jean-Philippe Cresceri

In the 2016 memoir, A Girl’s Story, Ernaux writes about her long-buried and traumatic coming-of-sexual-age journey as a naïve 17-year-old camp counselor. Although it took her 60 years to write about it, she confesses it was this experience that set her course as a writer.

“I started to make a literary being of myself, someone who lives as if her experiences were to be written down someday,” she wrote.

So yes, Annie Ernaux goes to the Auchan superstore and records her experiences for a year. She has mined another personal experience for a book.

In the end, she admits that the Auchan store, empty of customers one morning, gives her a “hallucinatory feeling of excess” and that she is often “overwhelmed by a sense of helplessness and injustice” when she leaves the store.

“But for all that, I have not ceased to feel the appeal of the place and the community life, subtle and specific, that exists there,” she writes.

I for one will never go through another checkout line – automated or not – without thinking about Annie Ernaux.

Alison L. Strayer translated Look at the Lights as well as some of Ernaux’s other works, including The Years and A Girl’s Story.

Pat Reber, 76, a retired journalist living in Maryland, has worked as a reporter and editor in New York, Washington DC, Germany, Kenya and South Africa. She covered the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings in South Africa for the Associated Press and served as deputy bureau chief in Washington for Deutsche Presse-Agentur (dpa) during the Bush and Obama years. She last wrote commentary for ArtsFuse on Annie Ernaux’s award of the 2022 Nobel Literature.

Tagged: A Margellos World Republic of Letters Book, Alison L. Strayer, Annie Ernaux, Look at the Lights My Love

Interesting and informative review. I think I’ll skip this book but look at some of the others!