Music Commentary: The Place Between “Classical” and “Jazz” Becomes a Destination

By Steve Elman

2022 was a year in which hybrid musical forms reached more Boston audiences than ever before. 2023 promises to open even more doors. The Place Between is no longer dangerous territory, a detour, or a side road. It has become a destination in itself.

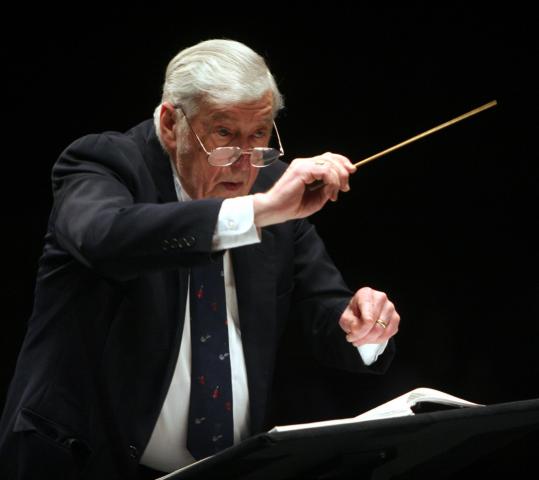

Gil Rose, music director and conductor of the Boston Modern Orchestra Project, whose recordings and concerts offer some great examples of cross-genre excellence. In 2022 he began a multiyear BMOP series of operas by composers of color with Anthony Davis’s X. Photo: Liz Linder

It may not be a trend, but it is far more than a trickle.

The Boston Symphony Orchestra continues its series of concerts spotlighting performers and composers of color, which sometimes include works that involve improvisation by the soloists, often conducted by Thomas Wilkins.

A department of the New England Conservatory evolved from Third Stream to Contemporary Improvisation to Contemporary Musical Arts, recognizing that music that crosses the artificial boundaries of genre needs a home and a proving ground.

Pianist Donal Fox creates an entire career innovatively mixing music from the classical and jazz traditions without fear or apology.

Mark Harvey and Darrell Katz continue their quests to bring music that combines composed and improvised elements — Harvey with his army of generals Aardvark, and Katz with art songs based on his late wife’s poetry, and concerts with his colleagues in the Jazz Composers Alliance.

The Boston Modern Orchestra Project inaugurates a series of operas by composers of color with Anthony Davis’s X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X, which includes notable improvised solos by trombonist David Harris, a member of the Jazz Composers Alliance.

Boston Lyric Opera presents Terence Blanchard’s opera Champion, which includes significant portions using jazz rhythm.

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum continues its series of chamber music concerts, which include at least one concert annually featuring performers of color who include works that cross genre boundaries in their programs.

Those examples are only the most notable ones offered recently in eastern Massachusetts. What’s even more significant is the way audiences have responded to these performances with enthusiasm for the one-shots and keen loyalty to the continuing efforts.

Things are changing throughout the music world, not just in Boston — where, truth be told, shifts in the artistic landscape happen more slowly than they do in other markets. Here and elsewhere, 2022 was a year in which hybrid forms came to larger audiences than ever before, and 2023 promises to open even more doors.

There is now such a significant body of work in the space between genres, such a long track record of tentacles stretched from one ocean to another, that a significant audience has grown for music that crosses boundaries. The potential listenership today for composers and performers of hybridized art music is greater than it has ever been.

Artists resent labels, but labels help listeners.

Artists want to follow their inspirations, but they do so at the risk of making music only for themselves. Even the most rigorous academic classical composer, secure in tenure at a major music school, must at some point engage with the audience — even to the point of suggesting (as Milton Babbitt has done) “voluntary withdrawal from this public world [of mass-audience performance] to one of private performance.”

Pianist-composer Donal Fox, whose entire career has been an adventure in the Place Between. Photo: Lou Jones

Consumers of music approach it in an entirely different way. Their attitude (even the attitude of very astute listeners) may be crassly summarized as “give me what I want when I want it.” Labels help them sort the music they might like from the music they want to rule out.

One of the essential facts of consumer behavior is that people tend to choose new things that are similar to things they already like or things they already value. This is what drives the programming of the algorithms that create online “personal playlists” for the music streaming services — they compile what you have previously chosen to hear, and then try to match your choices with those of similar users, or with selections that curators have put in baskets that they think approximate the baskets you have chosen.

This basic consumer fact works against artists’ impulses to use all of the things that may inspire or interest them.

The curse of any hybrid music — music that fogs or confounds a listener’s expectations of what a genre is “supposed to be” — is that it works in exactly the opposite way from how the creator expects it to work. Instead of attracting listeners of both genres, the combination repels those who are not interested in (or even put off by) the genre they do not know. The appreciating audience for any hybrid is thus exponentially narrower than the audiences for either of the genres that are part of the hybrid.

That fact is one of the most heartening things about the growing audience willing to go to the Place Between: a large number of listeners now accept the value of hybridity. They may not even think of works in the Place Between as crossing boundaries.

The ground for this change has been well-plowed by classical composers, though their audiences have not always been receptive.

It has been noted, to the point of tedium, that many of the sacred composers of classical music — Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven, just to name the most famous — were also great improvisers. Audiences accepted and applauded them as virtuosi-composers. During performance their double identities were completely intertwined.

But music from classical composers that reached beyond the accepted and conventional idioms did not become a phenomenon until the 20th century, despite the iconoclastic works of Charles Ives (1874-1954) in the nineteenth century. Harry Partch (1901-1974), Alan Hovhaness (1907-2000), John Cage (1912-1992), György Ligeti (1923-2006), Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928-2007), David Amram (1930- ), and others sought to broaden the materials available to the classical composer by using instruments of their own design, art and folk streams from non-Western cultures, chance elements, new systems of notation, and electronic devices.

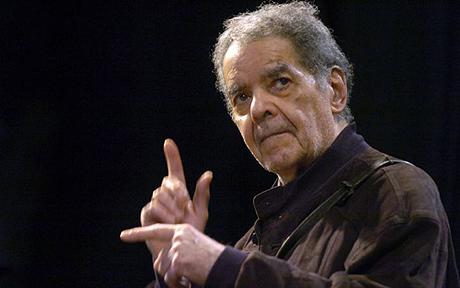

Composer Gunther Schuller, inventor of the term “Third Stream” and

exemplar of cross-genre experimentation from the classical side. Photo: Bruce Duffie

Most importantly to the jazz tradition, Gunther Schuller (1925-2015), a passionate lover and scholar of jazz, crusaded for the genre to be imported into composed classical works. He put his pen where his mouth was with a series of pieces that incorporated improvisations by the world’s best jazz musicians. Schuller’s Third Stream pieces were met with scorn — initially from classical critics — but with at least a kind of grudging curiosity from jazz aficionados. These pieces were primarily marketed to the jazz side of the market because of their performers.

These hybridizing efforts were always seen by classical listeners to be experimental, marginal to the classical music “mainstream.” What has really changed the collective mind of the classical world is the way that crossbreeding has become essential in popular music.

The appetite of popular musicians to reach large audiences has led to a proliferation of genres and subgenres. Hybrid ideas have become categories in themselves. Critics try to keep up and find names for what they are hearing, but there are now so many shades of popular music that an outsider needs a field guide to begin to understand what is meant by each neologism invented to define a new style.

This churning on the popular music side has tantalized the imaginations of composers and performers in the worlds of jazz and classical. But these two forms have dealt with hybridization in very different ways — or at least their audience reactions to the new amalgamations have been very different.

Both audiences still have a large majority of listeners who want “more of the same but different,” but jazz listeners accept a greater degree of experimentation. Because its players have never felt bound by what critics might decide is “traditional,” jazz, amoeba-like, has soaked up music genres of all sorts. From Louis Armstrong to Charlie Parker to Betty Carter to John Coltrane to Steve Lacy to Albert Ayler to Snarky Puppy to Maria Schneider — somehow all of the amazingly diverse musics these artists have made have ended up being perceived by their listeners as jazz.

Jazz musicians who have ventured deeply into formal composition are a special case unto themselves. Once a swing pulse disappears, or it is not easy to discern where the improvisation begins, a lot of jazz listeners find themselves at sea. When Charles Mingus and Ornette Coleman and George Russell pushed the boundaries, they brought passionate fans with them, but left many others behind. Those with the biggest ears have accepted even music that has a sort of “jazz scent” as part of the jazz tradition.

Conductor Thomas Wilkins, who has been at the podium for some of the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s most important concerts of music in the Place Between. Photo: Kaylor Management

The classical audience has been much more resistant to hybrids than has the jazz audience. As I noted earlier, those classical composers who dared to defy expectations dramatically, along with those who would not adhere to familiar forms and harmonies, have suffered indifference at best and walkouts at worst for more than a century. It is to the great credit of symphony orchestras and music directors in the major metropolitan areas that, since the ’40s, they have continued to champion composers with iconoclastic ideas — though, even in 2023, you have to look long and hard in the programs of orchestras in smaller markets to find anything beyond mainstream repertoire.

That perseverance on the classical side is finally gaining traction with audiences. What’s more, composers who have emerged from the jazz tradition are bringing enough listeners along with them to build a new audience from the other side. Partly because of what has happened in popular music, the Place Between is no longer dangerous territory, a detour, or a side road. It has become a destination in itself.

It isn’t all sweetness and light.

This writer, at least, has some questions, or perhaps they are merely topics for deep thought. How important is the reproducibility of a formal compositional conception, either in jazz or in classical?

More fundamentally, how significant, how valuable, is a work that depends so much of a composer’s personal involvement, either as player or as mentor? Is something universal being sacrificed when interpretation in the moment is so crucial?

Future generations may well wish to reinterpret music made in our time. But music which relies so much on improvisation and/or interpretation of nontraditional scoring will present considerably more problems to future interpreters than music written with conventional notation. Surviving recordings will allow any interpreter of the future to compare a score as written with how the music was actually performed. But when the composer is dead, a score is only as effective as future interpreters know how to read and understand it. And that fact puts in jeopardy the long-term survival of any particular work in the Place Between.

George Russell conducting in 2005. One of the greatest of all jazz composers, whose harmonic insights revolutionized jazz and whose large-scale works set standards that have rarely been equaled.

In the jazz tradition, this problem is already seen in music that has been conventionally notated. Jazz composers have always understood traditional notation as an approximation: a framework for the improvised portions that are so important for full impact. In our own time, we are seeing the music of Duke Ellington and Charles Mingus and George Russell wither away — not their recordings, or their written scores, or their popular tunes. What is disappearing are listeners’ memories of the performers’ idiosyncratic interpretations of their own music, which were so vital, fascinating, and essential. These living performances were expressions of the composers’ own restless personal artistic quests. The most dedicated revival ensembles — the Mingus Dynasty Band directed by Sue Mingus, the Duke Ellington Orchestra led by Paul Mercer Ellington, the Ellington Legacy Band led by Edward Kennedy Ellington II, the Gil Evans Project led by Ryan Truesdell, the revivals of George Russell’s pieces at the New England Conservatory led by Ken Schaphorst and others, and even Wynton Marsalis’s Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra — are the exceptions that prove the rule. When one hears them, one is hearing other people’s interpretations of the original ideas, no matter how “authentic” the interpreters may want them to be.

How are these reinterpretations different from modern reinterpretations of Beethoven’s or Mozart’s musics? To some extent, as the original instrument movement has shown, performances of these works by contemporary orchestras have refashioned these masterpieces gradually and radically. There may be no intention of violating their original spirit — in fact, the intent may be the exact opposite. The sound of the modern orchestras playing Bach, Vivaldi, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert — and all the other composers whose works were written for premodern instruments and ensembles — inhabit a different auditory world from the worlds of the originals. Although the emotional impact of modern performances of these works may be similar (or even greater, depending on your point of view), they are indubitably different.

In the case of music that emerges from the jazz tradition, the comparisons with original performance are more immediate and more startling. One can compare a recording of Ellington’s work with a performance by any of the subsequent Ellington family ensembles. Even if the performances are identical note-for-note, the spirits of the two will be very different — the originals are irreproducible examples of creativity in process; the moderns are homages.

Composer Wadada Leo Smith. Photo: Jimmy Katz

So contemporary composers writing music that involves so much interpretation of graphic scores and/or improvisation are taking a great risk. If these works are recorded — as many are today, privately or commercially — they could be transcribed or approximated using conventional notation and preserved after a fashion. But the original spirit of the works could not be captured in this way. Some of these modern composers, like Wadada Leo Smith, seem to be particularly courageous: it appears they want musicians of the future to be creative, to discard an obsessive devotion to “what the composer wanted.” If hybrid works live to be played another day, future interpreters may have to follow that path as a kind of default, with at least some precedent.

But most contemporary composers are too active in their own quests for self-exploration to be very concerned with these hard issues. The truth is, they must consign them to the strategies of future interpreters anyway, no matter what they may think or say during their lifetimes.

A final question, and a challenge: where is the iconic work that will open the Place Between to listeners who don’t even know it exists?

There is a paradigm — one that is so well-accepted now that almost no one remembers it once was controversial: George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” (1924). The incorporation of what was thought of as “nonclassical” harmonic elements (and — horrors! — jazz inflections) in “Rhapsody” outraged defenders of the genre boundaries of the time. It took decades for “Rhapsody” — and the much greater work that followed, Gershwin’s Piano Concerto in F (1925) — to migrate from Pops programs to the regular seasons of symphony orchestras in the US.

But “Rhapsody” took the world by storm. Its obvious appeal and its jazz feeling were immediately accepted in Europe as expressions of the American character. It found widespread acceptance in concert halls as European performers became comfortable with how to play it. It also inspired European composers to begin incorporating jazz elements in their works even before American composers did.

There are other paradigms. Igor Stravinsky’s “The Firebird” (1910) and “The Rite of Spring” (1913) were different kinds of hybrids, ballet scores with harmonic language that was new to many listeners. But they so lifted hearts and spirits with their drama and earworms that they became part of the mainstream repertoire.Today they are performed more often as stand-alone music in the concert hall than with the dance elements.

West Side Story (1957) by Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim (with Jerome Robbins and Arthur Laurents) fused Shakespeare, the American musical, jazz, modern dance, and classical music into a work beyond category. The 2021 film revival, updated by Stephen Spielberg and Tony Kushner, showed just how much life is still in it.

Otto Preminger conferring with Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn on the score for Anatomy of a Murder. Ellington is the Godfather of the Place Between. His imagination never limited itself to “jazz.”

On the jazz side, the paradigms are also landmarks:

Duke Ellington’s Black, Brown, and Beige (1942) was the first jazz symphony, so ambitious in its scope and form that it continued to be questioned by critics for decades, as the composer reinterpreted and refashioned it and found new ways to invigorate its ideas.

Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue (1959), which included classics like “All Blues” and “So What,” introduced millions of listeners to unusual extensions of the traditional solo framework and to George Russell’s innovations in modal harmony. But the music was so immediately communicative that no one needed a guidepost to understand it, and the recording is now the most popular jazz album in music history.

The Miles Davis-Gil Evans collaboration Sketches of Spain (1960) not only put Spanish traditions forthrightly into combination with jazz, but introduced classically oriented orchestration to the broader jazz audience and created the first genuine classical-jazz fusion, an interpretive refashioning of themes from Joaquin Rodrigo’s “Concierto de Aranjuez.”

John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme (1965) incorporated more extensive modal improvisation than Kind of Blue had done, but its powerful spiritual message and heartfelt emotion made it a work that transcended categorizing.

And any list of paradigms has to include some of the gorgeous miniature masterpieces, like Scott Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag” (1899); Duke Ellington’s “Black and Tan Fantasy” (1927) and “Ko-ko” (1940); Thelonious Monk’s “’Round About Midnight” (1957); and Charles Mingus’s “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat” (1959).

Works that broke through the genre boundaries (and still speak to a large audience) share something essential — in a phrase, that something is melody that strikes the heart and opens the spirit. And this is the kind of work that is needed now from composers working in the Place Between.

Some composers may feel that singable melody is too easy, too obvious, too simple. But if such a goal is so easily achieved, where is another work with the limpid purity of Frédéric Chopin’s Prelude in e-minor (Op. 28 No. 4, c. 1839) or Claude Debussy’s “Clair de lune” (1905)?

Some composers have left their hearts on the field of battle, seeking intellectual profundity (or the plaudits of a Pulitzer committee) at the expense of direct communication. It takes courage to buck the opinions of your peers. And not every composer has the greatness of spirit to make the attempt to be profound and direct at the same time. In fact, finding something so essential that it cannot be denied, and finding the means to fully express that something, are some of the hardest tasks facing any artist.

Is the mass audience even capable of being reached by such a work of art music at this time and in this ethos? The only answer to that question is to make the work that will find popular acceptance.

We have the opportunity in the coming years to see many more works in the Place Between. It is the result of composers’ inspirations as well as audiences’ growing familiarity with the territory. We can and should revel in what may come to be seen as the first golden era of hybrid art music. Everyone who loves the experience of spontaneous creation in a performance space should make it a point in the coming years to hear and think about the works that are going to be produced. They are and should be living testaments to the triumph of creative energies over the artificial boundaries of genre.

But composers and performers of hybrid music must not become complacent in the glow of standing ovations. They must hear the urges in their own hearts to find a universal that will speak beyond time and genre. They should reach for the stars, and sing.

MORE

Note and caveat: This essay contemplates music in the Western traditions. I am well aware that there are vast musical traditions of the Far East, Africa, and the Subcontinent where oral communication and person-to-person teaching are primary modes of transmission and preservation — and now these forms are developing hybrid paths of their own — but these musics go well beyond my scope here.

Ran Blake at the piano. Photo: Andrew Hurlbut

In 2014 and 2015, I explored (some would say exhaustively) the Place Between in a series of Fuse posts about jazz-influenced piano concertos. This essay is a summary of the conclusions I reached as I moved through the dozens of works I found.

Ran Blake, that indefatigable pioneer of the Place Between, read a draft of this essay and noted a host of visionaries who inspired and continue to inspire him. He counseled me that I should not fail to mention them, so I will list some of these great names here: Duke Ellington, Billy Strayhorn, Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln, Gil Evans, Wynton Marsalis, and Blake’s colleague Hankus Netsky, who (among others) spearheaded the revival of klezmer music, itself a venerable hybrid form.

In connection with this essay, I have provided a companion post with a calendar of 2023 concerts spotlighting hybrid art music in Boston. (In the works is a look back on Milestones in the Place Between — significant past events, landmark concerts, and recordings that have stood the test of time.) Your suggestions for these posts will be much appreciated — feel free to send ideas to steveelman@artsfuse.com.

Thanks to Doug Briscoe for comments and ideas which helped to shape this essay.

Steve Elman’s more than four decades in New England public radio have included 10 years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host on WBUR in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, 13 years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB.

Tagged: Boston-Lyric-Opera, Donal Fox, Duke Ellington, Gil Rose and the Boston Modern Orchestra Project, Gil-Rose, Steve Elman

Steve, thanks for your excellent piece. I wanted to mention early explorations, pieces for piano, written by Bix Beiderbecke (or rather, improvised and transcribed by Bill Challis): “In a Mist,” “Candlelights,” “Flashes,” and “In the Dark.” Had Bix survived, I’m sure he would have expanded his forays in this area.

Nice article, but hey man, it’s hard to imagine that someone could look at genre and style surfing, particularly related to classical and jazz, and omit John Zorn, the most prolific of all.

Quite an exhaustive piece; but, like one commentator, I miss Mr. Zorn and also Morton Gould, whose “Boogie-Woogie Etude,” at the very least, caught something that Gershwin himself may have missed in the Three Preludes.

Yes, John Zorn is indeed an important figure in the Place Between. Mea culpa, and I thank Gary and Paul for mentioning him. The Gardner Museum is celebrating his 70th birthday in a series of concerts this season. Already gone by is a three-guitar show with Bill Frisell, Gyan Riley and Julian Lage playing Zorn’s “Teresa de Avila”. Zorn himself will play with his New Masada Quartet (Lage, Jorge Roeder, and Kenny Wollesen) on 10/22 (sold out already). The series concludes with pianist Stephen Gosling playing Zorn’s “18 Studies from the Later Sketchbooks of J. M. W. Turner” on 11/19. Kudos to the Gardner for doing this, and may the success of this series inspire them to do more.

Gary’s mention of Morton Gould gives me the chance to tip my hat to Gould as a perennially underrated figure. I would point listeners especially to his “Interplay” aka “American Concertette No. 1” (1943), which Gould himself recorded playing the piano part in 1947. It’s a brief but fascinating piece, showing a real gift – a debt to Gershwin, but a lot more, too.

Thanks, Steve P, for mentioning Bix. The four lovely impressionist-influenced piano pieces that he wrote are part of the landmarks in the Place Between, without a doubt. I wonder how much they are really improvisations that Bill Challis formalized. Bix had piano training, and I suspect he thought of these pieces as his (first) contribution to the classical tradition. He probably worked with Challis to clean them up but I believe the pieces were more than improvs.

Challis said Bic never played it the same way twice. He just made a choice about what to set in stone.

Who’s Bic? Bix.