Poetry Review: Hannah Sullivan’s “Was It For This” — The Harsh Reality of Our Transience

By Leigh Rastivo

The structure, plot, themes, tone, and diction of Was It For This all combine to consecrate the ordinary alongside the exceptional.

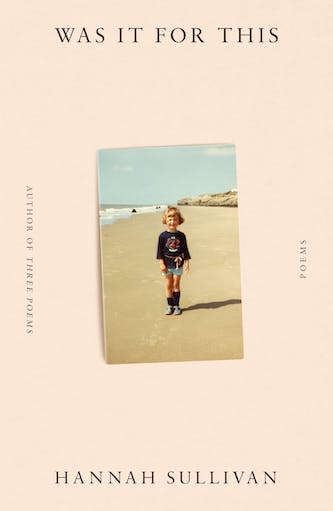

Was It For This by Hannah Sullivan. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 107 pages.

Good storytelling transcends its individual components. Words, themes, and structure might all stand alone as exceptional but, when entwined skillfully, they reinforce the power of the larger vision. The resulting aesthetic unity shimmers, its dazzle overwhelming all. Hannah Sullivan’s new hybrid collection Was it For This is transcendent in this way — the structure, plot, themes, tone, and diction all combine to consecrate the ordinary alongside the exceptional.

When Sullivan’s debut collection Three Poems won the 2018 T.S. Eliot Prize, a judge noted that readers “are so compelled” by Sullivan’s message that the masterful architecture of her writing is almost invisible. This structural dexterity is once again on display in Was It For This. Sullivan adeptly constructs a path of complex associations that resonate via the use of seemingly simple words. For example, the title — Was it For This — is just four one-syllable words borrowed from Wordsworth’s The Prelude. Yet, right up front, it presents the reader with an enigma: What is the “this” in Was It For This? And even if the “this” can be defined, how do we answer such a tantalizingly ambiguous question?

Fortunately, Johnson provides a solid framework in which to explore this difficult mystery. The book is parsed into three sections, each a poetic story with a defined focus. The first section, “Tenants,” is an elegy to the tragic 2017 Grenfell fire in West London, wherein a 14-story tower of apartments burned, killing 72. The section begins with the devastation, supplying an image of impermanence. Beneath the title “Tenants” only these words appear:

…but as

Fishes glide, leaving no print where they pass,

Nor making sound…

That is all. The ellipses at the beginning and end indicate a presence in medias res that may have proceeded into invisibility — a metaphor for any tenant of the planet who has gone on and is forgotten, or for the actual tenants who passed away at Grenfell.

On the second page, the date and time of the fire appear as the heading, and a four-part poem ensues, its sentiments bewildered: “To think of an event, a thing that happened/To understand how vague it was/How confused, uneventful, out of time.” The narrator is close by during the Grenfell fire, but she is absorbed with new motherhood. As the tragedy and its aftermath smolder, she is so focused on her newborn that the neighborhood catastrophe only registers when a friend from America e-mails to check on her. She is: “Cocooned, minutely logging feeds/Self-made servant of [her] selfish genes./A mile away.”

In its fourth part, this beautifully conjured poem dives into the nightmare, challenging us to mull over the fate of the youngest lost in the fire, suggesting what might be gained from the empathetic exercise: “If you can think about the child whose favourite song/ Was run, run, as fast as you can… and “the kitchen as it was” before the fire, and the “rectangle of ash” it became after, “You’ll see the vacancy it always was,/The eagerness with which all things disperse.” Thus the first section leaves us heavy with the harsh reality of our transience.

Poet Hannah Sullivan. Photo: Faber Books.

The next section holds the title piece “Was It For This” (an echo of six lines from The Prelude) and is somewhat lighter, comprised mostly of prose that recounts the narrator’s childhood in London, time in New York and San Francisco, and later life in London again. The section is fixated on concepts of home — childhood houses, the “good investment” value of even “shabby” real estate, grandmothers’ homes, first apartments. Throughout, Sullivan continues to recast plain words in ways that illuminate emotive truths. For example, the essence of homelessness: “The people in sleeping bags outside the station were sleeping rough.” And when the narrator decides to declutter her home, forcing herself to throw out or give away excess things, she begins to experience “a stuckness in time, a clinging on” and questions her perspective. Eventually, she asks: “…why should time only/in taking things, in/handing down, make/what they were all along/flare to brilliance…” Remembering becomes an act of resurrection, wherein a regular object is elevated by a flash — a “flare” — when we recollect it. Within these few lines the narrator, deftly placing the word “why,” also interrogates the idea that “time only” should romanticize or modify memory.

Fittingly, by the end of the section, time is not so much modifying memories as it is completely infused with them. The poet drives out to Oldfield Circus, the place where her life began. She does not even “need to take [a picture]” because she is so “mired” in time, there is no “record of or memory” existing or required. The past now overlaps the present, and narrator sees that as signifying stable order:

When…the once unexceptional post-war consensus is a clearly quixotic

mid-century whim,

When, Europe now over, you trawl around Lidl, and reach for a Spanish-

style platter of ham…

Then the time left to come and the time that has gone will be placed in the

pans of the scale and find balance

The third and last section of the collection, the poem “Happy Birthday,” begins with an epigram of openness to what is coming — “apertique futura” — as well as with an overt declaration by the narrator “…to devote [her] remaining/life to time, this thing we live…” (as opposed to the poet’s earlier preoccupation with space). Sullivan once again jumps from everyday activities and images — caring for children and feeding squirrels — to mammoth existential issues of age and illness. She describes a post-surgical body as “…a curio, a thing that,/having lost its use value, /is taken from the mantlepiece/to polish…” This prayerful juxtaposition of the prosaic and the philosophical continues with the narrator’s mother asking her what she wants for her birthday. The narrator tells herself several times that she desires life “…all of it again to do again,” but when responding to her mother, she says she would “love a chocolate cake.”

Was It For This closes with the poet kneeling to watch a moth spread its wings “in benediction” and asking “Why?” Why the reverence? The answer quickly follows: “No reason other than/each instant’s disregard/ being self-contained, for what might follow,/the flashiness of staring down/tomorrow.” Time is relentless and indifferent to our fate. Nevertheless, Sullivan reminds us there is a brazen alternative to disinterest — pay keen attention to the grace that’s here, in front of us, whether it be commonplace or extraordinary.

Leigh Rastivo is a fiction writer, reviewer, and essayist. Her shorter fiction has been published or is forthcoming in several journals, including the MicroLit Almanac and L’Esprit Literary Review, and she recently attended the Under the Volcano international residency to workshop two novels.