Poetry Review: “One Hundred Visions of War” — Haiku in No Man’s Land

By Jim Kates

This is a grim and uncomfortable book to read because it forces us to contemplate each small poem separately and then take them all together, a hard but necessary exercise.

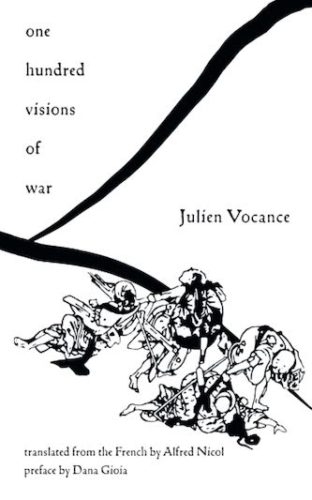

One Hundred Visions of War by Julien Vocance. Translated from the French by Alfred Nicol. Wiseblood Books, 122 pages, $12.

One country may embrace a culturally specific form of art that conforms to an aesthetic rule and may even have a ritual use. And then people from far away may appropriate it for their own uses, distorting it sometimes, usually watering it down, at other times wrangling about its “authenticity.” In our poetry we have done this most recently with the Central Asian ghazal and, during the last century — more notoriously and more deeply replanted into our own culture — with Japanese haiku.

One country may embrace a culturally specific form of art that conforms to an aesthetic rule and may even have a ritual use. And then people from far away may appropriate it for their own uses, distorting it sometimes, usually watering it down, at other times wrangling about its “authenticity.” In our poetry we have done this most recently with the Central Asian ghazal and, during the last century — more notoriously and more deeply replanted into our own culture — with Japanese haiku.

We will not deal with the original Japanese intricacies of the form. In its most simplistic form, taught to third graders, the American version of haiku is defined as 17 syllables divided into three lines. Slightly more sophisticated versions capture something of the ephemerality and nature-worship of its indigenous provenance. Occasionally an accomplished poet will use the form as a stanza in a longer piece — as Richard Wilbur did more than once.

Julien Vocance (the pen-name of Joseph Seguin) appropriated his own French version of the haiku to record the Great War in an ambitious sequence of 100 poems “written in 1916, in the mud of the trenches.” The verse’s reverberations have an iron ring. (When haiku is used ironically, focusing on human behavior, it is usually called senryu, a term Vocance did not employ, sticking with the French haikai.) The war poet was conscious of the dissonance of form and content: Vocance (1878-1954) gave his sequence the title Cent visions de guerre, with direct reference to Hokusai’s 19th-century series of prints, One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji.

Alfred Nicol has now brought these into English as One Hundred Visions of War. It’s a short book, and one small regret is that Nicol could not find space to include the original French alongside his translations, to enable us to read easily both the original artistry and his own.

Only a few of Vocance’s French texts match our English numerical formality of haiku, the 5/7/5 syllabic count, but Nicol hews much closer to this line with the majority of his versions. Thus, “Sentir / Que tout l’être s’effondre / Dans la faim, le froid et la peur” becomes in English,

To be made aware

that all existence ends in

hunger, cold, and fear.

As far as I have noticed, there are only a couple of missteps in interpretation, one of which occurs in the last poem in the book: “Deux levées de terre, / Deux réseaux de fil de fer: / Deux civilisations.” Nicol renders this as

Two rows of trenches,

Two lines of barbed-wire fences:

Civilization.

The dead triple repetition of “deux” and the resonance of two civilizations are both lost in Nicol’s strict preservation of the syllable-count.

It has been estimated that the French front in World War I stretched through more than 6,000 miles of trenches. It is this “Troglodyte World” (the term and statistics taken from Paul Fussell’s The Great War and Modern Memory) that Vocance documents in his verse.

Some of the poet’s perceptions are prosaic and simply documentary:

Far off

dogs howling at death …

They’re getting closer …

Others are far more evocative. “When all is said and done,” the English poet Siegfried Sassoon wrote about his own life in the trenches, “the war was mainly a matter of holes and ditches.” For Vocance,

The shell left a hole.

Reflected in its water,

heaven. All of it.

(“Un trou d’obus / Dans son eau / A gardé tout le ciel.”)

As a unified work, the collection is Nicol’s own, not Vocance’s. “I arranged the pieces according to a narrative I thought I saw in the work as a whole,” he wrote me in a personal note. I wish he had included this information in his introduction, because it makes a difference in determining how we read the book. In spite of the translator’s imposition of a narrative, the volume remains fragmented, as haiku should — capturing moments rather than eternal truths. How these moments coalesce into an eternal truth or two is left ultimately to the reader.

Overall, in tone, One Hundred Visions of War reminds me in its stark lack of compromise of Bertolt Brecht’s later War Primer (Kriegsfibel), without the latter’s photographs and far closer to the earth. A grim and uncomfortable book to read, it forces us to contemplate each small poem separately and then take them all together, a hard but necessary exercise.

J. Kates is a poet, feature journalist and reviewer, literary translator, and the president and co-director of Zephyr Press, a nonprofit press that focuses on contemporary works in translation from Russia, Eastern Europe, and Asia. His latest book of poetry is Places Of Permanent Shade (Accents Publishing) and his newest translation is Sixty Years Selected Poems: 1957-2017, the works of the Russian poet Mikhail Yeryomin.

An interesting take on Vocance. Why do you think he is not as well known as other WWI “trench poets”?