Book Review: Exile, Violence, and Cunning — Two Russian Authors After the Invasion of Ukraine

By Peter Keough

“It’s easy to see why we have such a lousy life and such great literature.”

Kilometer 101 by Maxim Osipov. Translated from the Russian by Boris Dralyuk. NYRB Classics, 296 pages. $17.95.

Telluria by Vladimir Sorokin. Translated from the Russian by Max Lawton. NYRB Classics, 352 pages. $16.69.

Russia has always been hard on its artists. Its harshness breeds geniuses, whom it then tends to oppress, imprison, murder, or force into exile. As Maxim Osipov puts it in Kilometer 101, his artfully conventional, Chekhovian collection of tales and essays, “It’s easy to see why we have such a lousy life and such great literature.”

Russia has always been hard on its artists. Its harshness breeds geniuses, whom it then tends to oppress, imprison, murder, or force into exile. As Maxim Osipov puts it in Kilometer 101, his artfully conventional, Chekhovian collection of tales and essays, “It’s easy to see why we have such a lousy life and such great literature.”

A cardiologist and public health activist as well as a writer, Osipov had long endured working under the inequities, stupidities, and cruelties of a system that glorified warfare. As a character in his story “Cape Cod” (written in 2013) says about the 1979 invasion of Afghanistan:

Can we even call it a war? Genocide, carnage, punitive action – take your pick…I’ve seen my fair share of sadness, even shame, in my time…but in such acts we can have no part.

But then came the invaision. Osipov packed up and left for Germany days after Putin’s would-be blitzkrieg crossed the border. However, as this collection shows, the idea of flight, of exile, has never been far from his mind. In the story “Little Lord Fauntleroy” a cardiologist much like Osipov moves from Moscow to a town just far enough away (the 101 kilometers of the title refers to the distance from the city that undesirables were restricted to in Soviet times) to escape the capital’s decadence, corruption, red tape, and cynicism.

Like Osipov, the story’s protagonist sets up a clinic to heal the neglected. At first he feels liberated, free to practice his profession among those who deserve it most, despite their alcoholism, ignorance, and petty prejudices. But his attitude changes radically after the police chief’s son puts a Tajik youth into a coma with a baseball bat. The thug had been inspired by similar scenes in Aleksei Balabanov’s 1997 post-Soviet gangster film Brother. (Osipov archly notes that bats but not gloves or balls are available in Russian sporting goods stores.) But when the doctor’s attempt to help the victim insidiously backfires, he realizes that not only has he not escaped the systemic evil but he has become a complicit part of it.

In “Luxemburg,” Sasha, a young man with a troubled marriage, has no career expectations. He moves from Moscow to the village of the title (named not after the country, but after Rosa Luxemburg, the revolutionary murdered by right wing thugs in Germany in 1919). He settles into a house owned by his recently deceased mother, a forbidding figure who survived decades of service to the party. Sasha’s move, in part, was to escape the oppressive shadow of his still living father, a failed musician. But he has also relocated for more existential reasons — he was shaken when he witnessed a mob hit unfold on a crowded street in the middle of the day.

But his new residence proves to be problematic when someone steals the rosebush he planted on his mother’s grave. Then it is desecrated – his mother, though a gentile, kept the name of her late Jewish husband and Sasha’s stepfather. Someone had scrawled swastikas on the headstone and defecated on the plot. He reports the crime and, after meeting the incompetent and unenthusiastic local police inspector, has little hope that justice will be done. But to his surprise they catch the culprits – a couple of ignorant yokels. Yet he is torn about pressing charges. What will it accomplish? Certainly the Russian prison system will not rehabilitate this pitiful pair.

In his essays Osipov is less forgiving of the faults of his countrymen. He lists them in “My Native Land.”

The first and most dreadful one is this…a fear of death and a dislike of life.

…

Second: power is split between money and alcohol, i.e., between two manifestations of Nothingness, emptiness, death.

There are more, but they all follow from these two. Who is to blame? And, to quote the title of Lenin’s 1902 novel, what is to be done? Osipov doesn’t say. He could heal the hearts of his patients, but not their souls.

Vladimir Sorokin, the popular author of such transgressive novels as Day of the Oprichnik (2006), has also left the country and now lives in Berlin. He had visited there by chance shortly before the invasion but is unlikely to be returning soon. Long a gadfly stinging the powers that be, he has escaped censorship or worse by setting his wildly violent, perverse, scatological, and savagely satiric works in an unspecified future. In a sense he has found a kind of temporal exile in his invented future histories while Osipov has done so geographically by living outside the 101 kilometer “forbidden zone.”

Vladimir Sorokin, the popular author of such transgressive novels as Day of the Oprichnik (2006), has also left the country and now lives in Berlin. He had visited there by chance shortly before the invasion but is unlikely to be returning soon. Long a gadfly stinging the powers that be, he has escaped censorship or worse by setting his wildly violent, perverse, scatological, and savagely satiric works in an unspecified future. In a sense he has found a kind of temporal exile in his invented future histories while Osipov has done so geographically by living outside the 101 kilometer “forbidden zone.”

The madcap, Swiftian Telluria, his most recent novel translated into English, is set in a period that is post the post-post-Soviet era of the ultra-hedonistic Oprichnik. A self-devouring Russia made an attempt to isolate itself behind an enormous wall. The wall failed and the country collapsed: the ruins of the unfinished barrier have become a popular tourist attraction. Meanwhile, as Europe barely survived waves of catastrophic jihadist conquests, the world has disintegrated into a patchwork of nation states, dictatorships, communist satraps, the fiefdoms of futuristic crusaders, and even a Stalinist theme park.

It is a postmodernist Dark Ages. Ironically, the breakdown of basic social structures has been paralleled by irresponsible leaps in technological innovation, including the invention of a phantasmagorical iPhone called a ‘smartypants” and genetically designed servant monstrosities.

Those in privileged positions laud the new state of things. Says one,

Take a look at the Eurasian continent: after the collapse of ideological, geopolitical, and technological utopias, it was finally plunged back into the blessed and enlightened Middle Ages.

Reflecting the fragmentation of this civilization, Sorokin has divided his book into 50 chapters written in styles ranging from manifestos to newscasts, from Beckettian dialogues to monologues in varying polyglot argots that must have challenged the considerable skills of Max Lawton in his outstanding translation. Episodes feature different characters, ranging from bio-engineered, walking and talking phalluses, to the Prince of Telluria, who heads a nation that enjoys the vast wealth brought in by its monopoly of the production of tellurium. A nail composed of this metallic element, when hammered into one’s skull by an expert craftsman, induces ecstasy, visitations from the dead, visions of blue kittens, and sometimes death.

How is tellurium different from the alcohol that Osipov lists among the top vices of the Russian people? Sorokin discusses the matter in a playlet that includes two biomorphic, dog-headed vagabonds, a poet and a philosopher. The pair cooks and eats the severed head of a warrior found in a battlefield full of rotting corpses. They come across two metallic objects in the dead man’s brain: a bullet and a tellurium spike. Says Foma, the philosopher, pondering this latter-day Yorick,

Yes! Two metals met in the head of this warrior – one noble and one not. And the head could not withstand their collision. The alchemical marriage of these two principles didn’t come off. It’s a tragedy. A sublime tragedy. ‘Twould seem the main battle did not take place near Bugulma, but in the head of this unknown hero.

The image epitomizes the soul of Russia, torn between materialistic greed and spiritual aspiration, both of which are illusory.

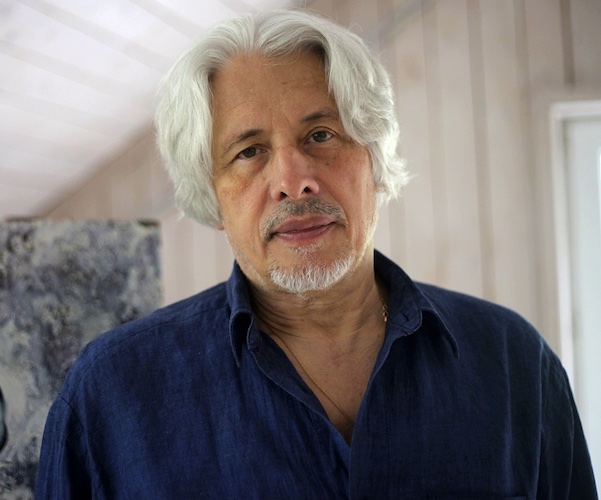

The polymorphously perverse imagination of Vladimir Sorokin is on display in the madcap, Swiftian Telluria. Photo: Maria Sorokina.

“In a single decade Russia changes a lot,” Osipov writes in his essay “My Native Land,” “but in two centuries — not at all.” Except, perhaps, in the polymorphously perverse imagination of Vladimir Sorokin.

And maybe now in real life. On November 18 The Economist reported,

Mr. Putin’s war is turning Russia into a failed state, with uncontrolled borders, private military formations, a fleeing population, moral decay and the possibility of civil conflict… there is growing concern about Russia’s own ability to survive the war. It could become ungovernable and descend into chaos.

It looks like Vladimir Putin’s present may be catching up with Sorokin’s dystopian future.

Peter Keough writes about film and other topics and has contributed to numerous publications. He had been the film editor of the Boston Phoenix from 1989 to its demise in 2013 and has edited three books on film, most recently For Kids of All Ages: The National Society of Film Critics on Children’s Movies (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).