Children’s Book Review: “Discovering” Thanksgiving

By Cyrisse Jaffee

Many Thanksgiving myths are dispelled, but the effort to reverse decades of misinformation leads to oversimplification at times.

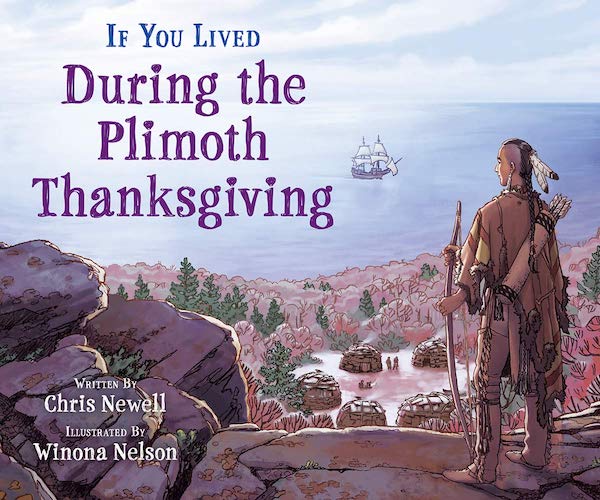

If You Lived During the Plimouth Thanksgiving by Chris Newell. Illus. by Winona Nelson. Scholastic, 96 pages.

As you prepare yourself for Thanksgiving — however you observe it — you might find it helpful to read about the true origins of the holiday. As Chris Newell (Passamaquoddy) explains in If You Lived During the Plimouth Thanksgiving, “the story of the Mayflower landing is different depending on whether the storyteller viewed events from the boat or from the shore.” Illustrated by Winona Nelson (Minnesota Chippewa), the book contains valuable, detailed information about the indigenous people, especially the Wampanoag people, who lived in the New England area for thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans. It also provides an in-depth look at the political, social, and ecological consequences of the resulting clash of cultures, beginning with the early European traders in the 1500s. Equally important is the naming of tribes and leaders so that the Native history is made clear and vibrant, rather than vague and general. We are often taught the names of the “Pilgrims” such as William Bradford, but not of the leaders Ousamequin (also known as Massasoit), Samoset, and Tisquantum (known by some as Squanto), or the Nipmuc and Narragansett tribes. One wishes that some of the “clan mothers” had also been named.

Many Thanksgiving myths are dispelled. Not everyone on the Mayflower was a “pilgrim” (a term used about 200 years later) seeking religious freedom. They called themselves Saints (those looking to separate from the Church of England in order to practice their religion their own way) and Strangers (fortune seekers, indentured servants, and others). The 1621 harvest feast was not called a day of “thanksgiving” until much later and was a misnomer anyway. Earlier encounters by the Native people with Europeans had resulted in disease and enslavement, which caused them to be cautious and/or hostile toward the new arrivals. The Wampanoag of Patuxet (later called Plimouth, then Plymouth) were part of a network of Algonquin-speaking nations who used sophisticated methods to farm, fish, and trade.

Despite the important Native American perspective, the effort to reverse decades of misinformation leads to oversimplification at times. Newell claims that [Native] “people respected one another’s territories and followed certain protocols when going into other people’s homelands.” In fact, there were conflicts and power struggles within and among tribes. Living a life that “followed the natural life cycles of plant and animal life” surely meant occasional shortages or weather-related problems. But the author writes that “there was no shortage of food resources in the Wampanoag homelands. Through their ancestral knowledge, they knew how to harvest and sustain it all.” No one can dispute the devastating impact of colonization, but by its very nature it is not “usual,” as Newell writes, “for people from one country to negotiate with the leaders of another country before settling there.”

The narrative is at times clunky and some words or phrases — curiously, not necessarily the highlighted words defined in the glossary — will be challenging for young readers. For instance, the author characterizes the Native approach to their homeland as “animate life” (as opposed to owning and “improving” the land as the Europeans did). The Mayflower was “at the mercy” of dangerous winds and the passengers were in “dire need” of food and water. More information on today’s Wampanoag people would have been a useful addition, as would a bibliography or list of sources. Nevertheless, one can imagine reading portions of the book aloud at the Thanksgiving table. Not only would it be a worthy history lesson, but it could lead to an interesting discussion of history itself — whose stories get most often told and why. Some now begin the meal by acknowledging whose ancestral lands they live on (see https://native-land.ca/). Perhaps the conversation will lead to the telling of some of your own family’s origin story.

Cyrisse Jaffee is a former children’s and YA librarian, a children’s book editor and book reviewer, and a creator of educational materials for WGBH. She holds a master’s degree in Library Science from Simmons College and lives in Newton, MA.

Tagged: Chris Newell, f You Lived During the Plimouth Thanksgiving, Thanksgiving