Poetry Review: “Burning at the Same Time” — José-Flore Tappy’s Mysterious Poem-Portraits

By Alina Stefanescu

Deeply indebted to her relationship to persons and places, José-Flore Tappy uses poetry as a way to revisit them, honoring the absent through poems co-created by memory and imagination.

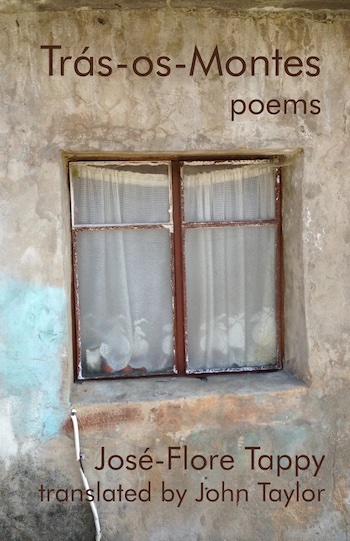

Trás-os-Montes: Poems by José-Flore Tappy, translated by John Taylor. MadHat Press. 189 pp.

Trás-os-Montes, which means “on the other side of the mountains,” is a remote, mountainous area in northern Portugal on the border of Castile. Swiss poet José-Flore Tappy titled her 2017 poetry collection, Trás-os-Montes: Poems, after this region. In an interview with translator John Taylor, she calls Trás-os-Montes “a country within a country, consisting of small communities gathered together into villages or small towns, which are today getting old and which have no future, communities that are confined by their poverty, by their ancestral mores as well as by brutal conflicts with tenacious roots.”

Trás-os-Montes, which means “on the other side of the mountains,” is a remote, mountainous area in northern Portugal on the border of Castile. Swiss poet José-Flore Tappy titled her 2017 poetry collection, Trás-os-Montes: Poems, after this region. In an interview with translator John Taylor, she calls Trás-os-Montes “a country within a country, consisting of small communities gathered together into villages or small towns, which are today getting old and which have no future, communities that are confined by their poverty, by their ancestral mores as well as by brutal conflicts with tenacious roots.”

Deeply indebted to her relationship to persons and places, Tappy uses poetry as a way to revisit them, honoring the absent through poems co-created by memory and imagination.

“To live one / must know nothing of the shadow / that falls into decay,” Tappy writes in the three-poem opening, which functions as a sort of prefatory invocation of a Virgin Mary icon known as “Dewy Virgin.” This icon is housed in the church of the Panagia Drosiani, the oldest Christian church on the Greek island of Naxos. According to local legend, the image sweats when the village is in danger. The icon works her miracles by labor, by sweat, promising that she will bring a cool breeze to protect them. One finds this in the name, drawn from the Greek word, drosiá meaning “coolness,” or “cool breeze.”

By italicizing the three prefatory poems, Tappy sets them apart, evoking the elegant permanence of words engraved on stone at the base of statue plinths. Despite the illusion of permanence, statues, like mountains, are ruined by time, eroded by “decay,” and this temporal tension, this desire to defy time’s linearity, may account for the sparse use of periods or closing punctuation marks.

The first section, Before the Night, is set in Trás-os-Montes and is dedicated to a peasant woman named Maria, whom the poet met on various trips to the region from her own native Switzerland. Focusing on the small, daily actions of village life as experienced by the peasant woman, the speaker seeks to paint a sort of mirror-portrait of her which serves as a light that illuminates Tappy herself.

The poet’s sparing yet luscious language relies on synaesthetic imagery and personification. “While the light outdoors / slumbers / under vanilla-colored broom plants”: the scent of vanilla infects the broom; the light slumbers; the surroundings absorb events and actions. Light is personified — it slumbers, it sleeps, it decides when villagers sleep, or what they do. Emotions and abstract states are also communicated through object-oriented metaphors: peace “has four wooden feet / and customary gestures” but peace does not have “a face.” Taylor’s translation makes skillful use of assonance — “the courtyard is a big misshapen / mouth / into which surges the shouting” — to thicken the images.

The absence of titling for individual poems adds to the dreamlike texture, and to the blurring of boundaries between portrait subjects, between Maria and the landscape.

Silence is good — silence is when the absent speak. The peasant woman allows silence to exist; she treats it as something watched “without impatience / like something urgent / and endless.” Tension builds between Maria’s small, ordinary actions, between motions, between the modernity of urgency and the timelessness of infinitude.

The poems testify to Maria’s unique, irreplaceable knowledge of seasons, farming tasks, and householding:

“She has always known these places

with their noises, their worries,

a leaking water pipe, the laundry

to fold and the pungent

smell of the kitchen,

her hands even know how to calm

the invectives.”

Mixed metaphors blur and bleed the boundary between Maria and the house: clouds behind the curtainless window “leave stains” which connect with the cherries Maria sorts in her kitchen. All is suffused by its relationship to the surrounding world.

The portrait of Maria evolves into a portrait of the poet, colored by how she has known herself through others. Repeatedly, one is struck by the extent to which Maria’s actions are inhabited by the one who watches her, a feat accomplished through the use of what Tappy has called an “augmented I,” or an “I” constructed from personal experiences and imagined projections.

Poet José-Flore Tappy. Photo: mauricehaas.ch

“Everything I carry attached inside me, somewhere is free,” wrote poet Antonio Porchia, whose lines Tappy borrows for an epigraph for the book’s second section. This part, The Blank Hour, is set in an unnamed location among the Balearic Islands. The object-oriented imagery continues: the speaker “reassures” a “trail” with her feet; the “blossoming trees / unfold their blankets.”

But the first-person voice of the first section expands into a “We” — as in “We knot up phrases” and “our voices crisscross at dawn / like blurry headlights” — which includes a male interlocutor.

The absence of this person is refused by the poem’s insistence on recalling him, or summoning him back into the spaces he occupied with her. Again, the place itself speaks — the place becomes the voice of the missing, the site of invisible reunion — in the rowboat he owned, which is now sleeping.

Taylor’s translation strategy stays very close to a literal rendering. The following passage, for example, tracks the French word for word, and line for line:

What remains of your passage

through my entire life

is this mere flimsy cigarette

lit in the black night

like a tear trembling

and burning at the same time

And Tappy is clear about the way landscape and place speak if one listens closely, if one stands at the edge of a hill to meet “the breathing of the missing, / the painful babbling / of those we have lost” who are now “buried … in the infinite.”

Tappy’s ability to honor Maria without descending into a regressive idealization of the bucolic prevents a facile political reading of her work. The section ends with a dedication to Anne Perrier (1922-2017), and one wonders if this is the name of the woman who inspired “Maria.” In this poet’s hands, the particular becomes panoptic and existential, it looks to be placed and situated, to exist in relation to.

Like the prefatory poem, the book’s final poem, “As the night,” is written entirely in italics. Tappy dedicates it to “Hemingway,” the mysterious interlocutor, presumably the poet’s former, the other “I” in the “We” of the book’s second half. I read this final poem as an extended envoi, a short poem that concludes a work, sending it off into the world like a wave from a departing ship. Here, the envoi addresses the reader intimately, its tone closer to a kiss than a good-bye gesture. It is a coda that seeks to meet the absent again and again, by listening, by writing, by attending the rhythms of silences, and resuming a dialogue with those who have passed from presence into infinitude.

Alina Stefanescu was born in Romania and lives in Birmingham, AL, with her partner and several intense mammals. Recent books include a creative nonfiction chapbook, Ribald (Bull City Press Inch Series, Nov. 2020) and Dor, which won the Wandering Aengus Press Prize (September, 2021). Her debut fiction collection, Every Mask I Tried On, won the Brighthorse Books Prize (April 2018). Alina’s poems, essays, and fiction can be found in Prairie Schooner, North American Review, World Literature Today, Pleiades, Poetry, BOMB, Crab Creek Review, and others. She serves as poetry editor for several journals, reviewer and critic for others, and co-director of PEN America’s Birmingham Chapter. She is currently working on a novel-like creature. More online at www.alinastefanescuwriter.com.

Superb review of deeply moving poetry. It’s rare that

an approach to poems measures and respects their

many qualities. Tappy is a deep imagiste, every word

clear and necessary. My only wish is that you had

connected the “We” section to “Tombeau” which concludes Tappy’s Hangars.