Book Review: Bob Dylan’s “Philosophy of Modern Song”

By Scott McLennan

The point of Bob Dylan’s project is emotional rather than definitive: to probe the power of song to influence us, make us feel, and ultimately transform us.

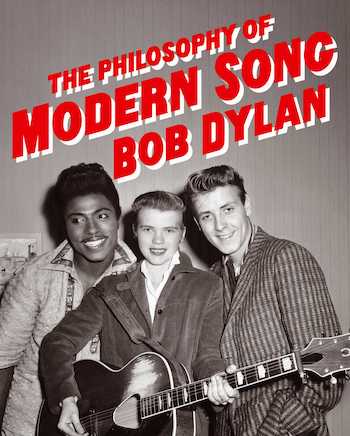

The Philosophy of Modern Song by Bob Dylan. Simon & Schuster, 352 pages, $45.

If you have ever wanted to argue about music with Bob Dylan, his new book, The Philosophy of Modern Song gives you the chance.

If you have ever wanted to argue about music with Bob Dylan, his new book, The Philosophy of Modern Song gives you the chance.

Dylan serves up essays on 66 songs, each piece sparking conversation of the sort you could imagine hearing in the aisles of a vinyl-packed record store or at the bar of a nightclub that keeps a small stage in the corner for the benefit of local musicians and the people who still love it live.

This effort is by no means Dylan’s catalogue of what he thinks are undeniably great songs. Rather, The Philosophy of Modern Song is a ramble through tunes that Dylan loves for all different kinds of reasons. The point of the project is emotional rather than definitive: to probe the power of song to influence us, make us feel, and ultimately transform us.

The essays vary in length and intensity: the book’s 340 pages are padded with photos and graphics germane to the speculative vibe.

Of course, a book like this, written by a songwriter who has inspired a cottage industry devoted to analysis of his work and his life, will feed right into said bloated industry: What is Dylan offering up about himself when he comments on other songs? Criticism as a form of autobiography.

Ironically, beginning with the opening piece on Bobby Bare’s “Detroit City” and through the rest of the book, Dylan pushes against the conventional notion that art is inevitably autobiographical. When it comes to songs, the listener’s reception and reaction are far more important to him.

And boy, does he have some interesting receptions and reactions to the songs he chose to write about.

Dylan imagines that the narrator of Webb Pierce’s “There Stands the Glass” is a war veteran who has been mentally and physically ravaged by his experiences in battle. There is nothing in the lyric to suggest that, but Dylan lets the song take his mind in that direction. He imagines who that person might be, looking at a glass of whiskey that promises to ease his pain and take away his memories. The essay also breaks into a side discussion about the creation of the flamboyant Nudie suit and its importance in country music. On the one hand, you can’t help but wonder how Dylan got to these conclusions. But you are grateful because they encourage the book’s sections of electrifying prose.

At 81, Dylan remains an arch, dissident critic of his surroundings, sounding no less defiant than he did on his early albums that served as beacons for other restless thinkers, activists, and artists who gravitated to his work in the ’60s. But this is a Dylan who has moved from the remonstrations of 1963’s “Masters of War” to supplying a laudatory list of military generals who “cleared the path for Presley to Sing/ Carved the path for Martin Luther King” in 2021’s “Mother of Muses.”

Bob Dylan is not an angry old man. Photo: David Gahr

By no means has Dylan simply become an angry old man feasting on Fox News all day. However, his discourse and perspective are firmly rooted in an admiration of the music that emerged between 1950 and 1970. Throughout The Philosophy of Modern Song Dylan bemoans America’s cultural and intellectual decline from that period. “This is the sound that made America great,” Dylan enthuses about the urgency heard in early Sun Records singles. He toys with today’s political vernacular again when writes in an essay triggered by “Saturday Night at the Movies” (which does not deal at all with that Drifters song) that “People keep talking about making America great again. Maybe they should start with movies.”

Dylan strongly challenges political correctness, extreme conservatism, and the ease with which a song or a movie is decontextualized and demonized. In Dylan’s eyes, the result sanitizes our cultural conversation. The purpose of the well-meaning muzzling may be to create a harmonious society, but setting up such limits ends up shutting down the kind of invaluable critical thinking that dares to challenge authority.

Dylan discusses how Pete Seeger’s “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy,” a sharp criticism of the Vietnam War, found a wide listenership because he performed it on the Smothers Brothers TV variety show at a time when “variety” meant exposing different kinds of art and entertainment to a mass audience drawn from all income levels.

Today, people are encouraged to gravitate toward their own self-designated tastes and beliefs. There is no longer a hunger to be confronted by the unknown, the unfamiliar, the possibly confrontational. Dylan pointedly argues that it “turns out, the best way to shut people up isn’t to take away their forum — It’s to give them all their own separate pulpits.”

Dylan is at his most acerbic in an essay that is ostensibly about the Johnny Taylor-sung “Cheaper to Keep Her.” He immediately veers into a screed about divorce attorneys that is filled with standard male chauvinistic tropes. Dylan sizes up the criticism he anticipates for his views and doubles down on the patriarchal taunts. In other parts of the book, Dylan’s anger, disgust, and disappointment spawn provocative observations and opinions that you may or may not agree with, but you can at least reasonably consider. In “Cheaper to Keep Her,” Dylan’s take is just plain ugly.

Aside from irrational ramblings, Dylan can be scholarly and passionate in digging into the mechanics of the songs he writes about. He makes many astute observations, such as how The Who’s primal “My Generation” contains the seeds to the grand themes of the rock opera Tommy. Or how The Clash, singing about making a home by the river, strike a universal chord of dissatisfaction — among those who see the Thames outside their window and those who live by the Mississippi. Both long for an escape from the bullshit raining down on them.

Still, Dylan cautions against over-analyzing songs to the point of neutering their artistic force. He celebrates the mystery of a masterful song, when the right words are combined with the right music. There is no predictable way to make that happen — which is why you can only admire, and learn, from those who have pulled it off.

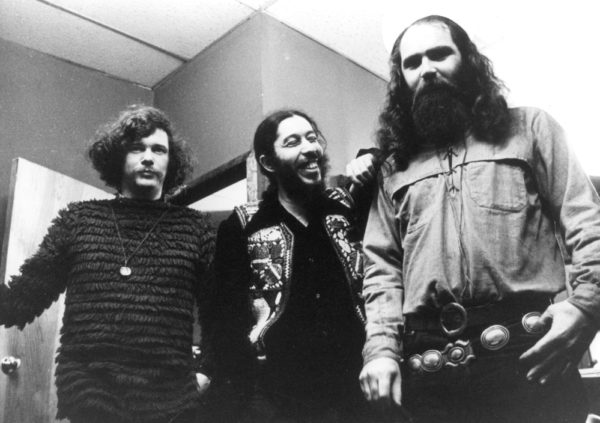

The Fugs — Dylan prefers the Fugs’ raunchy proto-punk “C.I.A Man” to Johnny Rivers’s catchy and slick “Secret Agent Man.”

Dylan, no surprise, embraces the heartfelt and authentic over the polished and precise. He much prefers the Fugs’ raunchy proto-punk “C.I.A Man” to Johnny Rivers’s catchy and slick “Secret Agent Man.”

Sometimes, as in the case of Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard’s version of Townes Van Zandt’s “Pancho and Lefty,” it is a matter of bringing all the elements, including performance, together. The chemistry of that writer’s work meeting those voices in that production — these elemental ingredients, on that occasion, create the monumental.

No stranger to protest music, Dylan lifts up the Temptations’ “Ball of Confusion” and Mose Allison’s “Everybody’s Cryin’ Mercy” as examples of how similar critical broadsides can be effective in completely different ways. Both the Temptations’ frenzy and Mose’s bemusement are equally effective in provoking outrage.

Dylan delves into the importance of nailing arrangements. He contrasts the intricacies of Marty Robbins’s “El Paso” with the predictability of Johnny Cash’s “Don’t Take Your Guns to Town” — and sees that both are of equal value. Dylan considers the skills of particular singers (big fan of Ricky Nelson and Bobby Darin) as well as the archetypes we identify with (outlaws, we like; criminals, not so much. And everybody loves a fool). He also goes into all manner of minutiae in explaining why a certain song leaves a lasting impression. For example, in cataloging songs about shoes, “Blue Suede Shoes” reigns supreme for many, many reasons.

Dylan U, if you choose to enroll, offers lessons in sociology, history, political science, religion, language, economics, psychology, and geography. And the coursework, aside from downward slides into misogyny, is humorous, expansive, and informative. Dylan authoritatively throws down controversial assessments and analyses here, but he invites agreement on just about everything. Aside from a shared understanding that, for our survival, songs are as important as air. If you disagree, you deserve neither.

Scott McLennan covered music for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette from 1993 to 2008. He then contributed music reviews and features to the Boston Globe, Providence Journal, Portland Press Herald, and WGBH, as well as to the Arts Fuse. He also operated the NE Metal blog to provide in-depth coverage of the region’s heavy metal scene.

Tagged: Bob-Dylan, Scott McLennan, Simon & Schuster

A wonderful take, Scott.. Interesting that Dylan makes a point of praising an idol of his early teen years, Ricky Nelson, since in his first book, “Chronicles,” he says that hearing Nelson’s likable, but slickly shallow “Traveling Man” in a Greenwich Village coffeehouse in spring of 1961 made him think the time had come for a deeper music.

Fascinating. There was one Christmas morning, six or seven years ago, when I was not speaking to my brother, and was alone dog sitting at a neighbour’s house. I scrolled Facebook and Bob’s site came up. It said ‘write a message to Bob’s… I did. I can’t remember what I wrote. Immediately a response came back, and then a sort of explanation in the ‘we are happy you are a fan’ kind of vein, then it shifted to private messaging. Somebody wrote ‘its me, Bob Dylan ‘… So now I was engaged in private correspondence with either Bob, or someone else saying they’re Bob. I shivered, gulped, and wrote my best ‘ honesty test’ by telling whomever that I had been on a bicycle trip in 1998 through Duluth, and had looked for clues to his early life there. In a camera store, some staff informed me that an old friend of his had an Italian restaurant nearby and Bob still kept in touch. ( I’m being as brief as I can here). The messaged wrote back and said, “you’re right; I do have a friend who owns, and runs an Italian restaurant in Duluth. You are a true fan from a long time ago.” He/ they also wrote ” I’ m reaching out across the world this morning to my fans…” I wrote excitedly that I had taken a sketchbook to a Toronto concert in 2008 and drawn him and the band from the third row. He replied that if I came to one of his shows that next summer he’d be happy to receive the drawings. He said ” we’ll be in Montreal and Toronto for sure”

I pushed on and said how moved I was by Patti Smith’s performance at his Nobel prize ceremony where she sang Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall. He said that ‘Patti is a very philosophical person who has lifted many souls’…

I’m Jewish, agnostic, but still sensitive to the tingly feeling of Christmas. Was I really engaged in conversation with Bob? Was it a hoax of some sort? After some sentences politely framed to not gush too much, I returned to the Facebook public site, publicly messaged that I’d just maybe, or maybe not, been messaging with Bob Dylan. Another subscriber replied to me “yep, that was really Bob. Nice exchange.. ” and this stranger was some dude named Marshall Tackett. That name struck me. Was he possibly a relative of Fred Tackett? Could this be a clue as to the authenticity of my Christmas morning exchange with my lifelong idol? I will take this mystery to the end, I am sure. Other phrases in our total exchange seemed like Bob- style diction.

I’m sharing this now, wondering if anyone out there has verification or de-verification information for me. I can handle either possibility. Sometimes I think it doesn’t matter whether it really was him or an imposter.

I did go to the Toronto concert. I brought a drawing. I coaxed security into taking it from me to try and deliver it to Bob, with a letter, of course, explaining everything. I haven’t had a response. It’s okay; it left me changed on that morning, for the better. Thanks ‘Bob’. God bless.