Visual Arts Review: “Fired Up: Glass Today” — Remarkable Beauty

By Peter Walsh

The dignified design and subtle lighting of the Wadsworth installation manages to keep the diversity, frenetic variety, and colorist’s dream of this exhibition from being overwhelming, while highlighting the individual qualities of each piece and of the glass medium itself.

Fired Up: Glass Today, a survey of contemporary studio glass at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art on view through February 5.

Caroline Landau, Archiving Ice (Svalbard 2), 2018. Blown glass, glacier water, and silicone. 3 ½ x 7 ¾ x 7 ½ inches. Collection of the artist.

Glass is arguably the most dangerous and difficult of visual arts media. “Glass is a really demanding, unforgiving, and kind of dangerous process,” says glass artist Kiva Ford. “It’s like a mediation almost. Really the only thing that limits you with making glass is your imagination.”

Over the last half century or so, the collective imagination of glass artists has expanded enormously. The American studio glass movement — which took glass out of its traditional environment of industrial mass-production and its focus on everyday practical and decorative objects — started, it is said, with two famous glassblowing workshops in 1962 at the Toledo (Ohio) Museum of Art. Organizer Harvey K. Littleton, a ceramics teacher at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, had been experimenting with new ideas about glass for several years. Littleton worked with glass research scientist Dominick Labino to develop a small, inexpensive furnace in which glass could be melted and then worked on in an artist’s studio. Back in Madison, Littleton started a glass program within his ceramics department. Among his early glass students were Dale Chihuly, Marvin Lipofsky, and Fritz Dreisbach, all of whom became key figures in the Studio Glass Movement.

Fired Up: Glass Today marks 60 decades of this remarkable effort, which has made glass into a full-fledged, independent artistic medium. The year 2022 is also the United Nations International Year of Glass, which celebrates glass as a useful, historic, and recyclable material with events around the world.

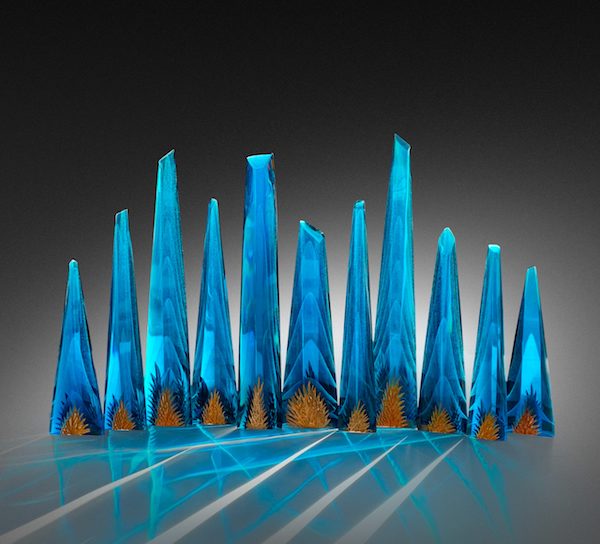

Alex Bernstein, New Spring Blue Group, 2021. Cast, carved glass, and steel. 25 x 45 x 6 inches. Collection of the artist. Courtesy of Habatat Galleries

A bit disappointingly, presumably because of transportation logistics and lack of space, the Wadsworth show omits the monumental glass works that have become so visible a part of studio glass in recent years: for example, the towering columns and cascading chandeliers produced by the Chihuly workshop and installed in public spaces like museums, concert halls, and casinos, or the elaborate floor installations that can fill entire galleries with hundreds of individual objects. These works usually require large loft spaces or the sort of specially designed galleries found at the Corning Museum of Glass in upstate New York.

What the show does contain, though, is a rich cross-section of the Studio Glass Movement’s members and a deeply satisfying selection of beautifully conceived, immaculately crafted, and brilliantly colored glass objects. Most of the selections are domestic in scale and have absorbed and digested a huge range of influences: from inside the glass world, from contemporary science and research, including biology, digital technology, and climate research, from trends and ideas in the wider range of contemporary art, and from pressing social issues — race and identity to the climate crisis.

Many of the exhibition labels mention the influence of Murano glass craftsmen who helped train them. Venice’s “glass island” of Murano has been home, for centuries, to generations of innovative glass workers whose technical skills and virtuoso productions were famous around the world. In 1968, Chihuly worked with a luxury glass manufacturer and school in Murano. When he returned to the US, he brought with him the idea of piazza, or glas- blowing team, which he introduced into his practice and teaching. Since then, the idea of team creation, in which glassmakers work together heating, blowing, rolling, and shaping glass pieces, has become an important part of the studio tradition, as have the intricate techniques of the Murano workshops, passed down for generations. Chihuly’s 1981 piece, Etherial White Sea Foam Set with Opal Lip Wraps, with its characteristic shell-like waves and ridges and pale, mysterious color, was made by a team and reflects the delicate designs of 20th-century Murano glass.

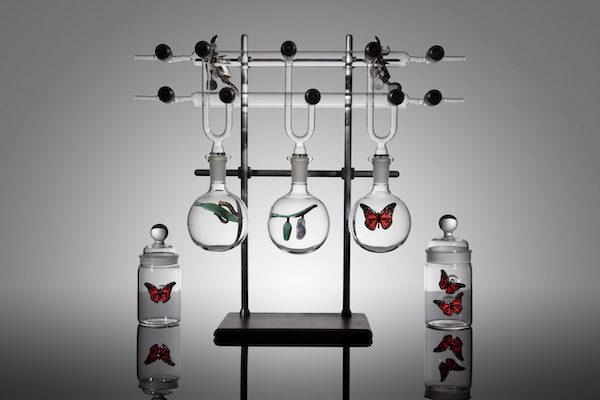

Kiva Ford, Metamorphosis I, 2015. Borosilicate glass and stainless steel. 14 x 22 x 8 inches. Collection of the artist. Courtesy of Chesterfield Gallery

Another important, if less expected, thread in the movement is the cannabis glass pipe (also known as “functional glass”). Its increasingly elaborate bent and embellished tubes were originally created and marketed originally for smoking pot, but were later admired for their aesthetic and technical virtuosity. “The glass pipe is American,” says David Colton. “I grew up immersed in hip-hop — Eric B. & Rakim, Public Enemy, the Beastie Boys. That’s when I started to do graffiti, and with spray paint, I’d spend every day doing my name, doodles, and that kind of stuff. My sculpture is rooted in this history of early graffiti influences, traditional Venetian glassware, and improvisational music.” Colton’s backlit Untitled (2022) features glowing streaks of red and lavender glass like the strokes of a graffiti tag come to life. In 2019, his piece for the Rakow Commission at the Corning Museum of Glass became the first glass cannabis pipe to enter a museum collection.

Glass, like ceramic, is also appreciated for its uncanny ability to imitate other objects and materials. Shayna Leib’s Patisserie: French Series (c. 2017-18) and Patisserie: American Series (2018-20) are spectacularly convincing renditions in glass and ceramic of dessert treats, peach pie à la mode, red velvet cake, macarons, mille feuille, and eclairs among them. They look more than good enough to eat but are, alas, forever unobtainable. Because of her food sensitivities, the real things are inedible for Leib, so, for her, “this body of work started out as a therapeutic exercise in deconstruction and a retraining of mind to look at dessert as form rather than food.” These creations in glass and ceramic “utilize nearly every possible technique in both mediums; glass blowing, hot sculpting, lamp work, fusing, casting, and grinding in glass, as well as the ceramic techniques of hand building, throwing, and using a good old-fashioned pastry tube.”

Jason McDonald’s Black Figure Number 1 (2018) imitates a classic Greek black-figure vase. The name of the original denotes a ceramic decorative technique, not a race. But the imagery of McDonald’s sleek and elegant glass version suggests an African American in a jail cell. “By making this work I hope to shed light, for myself and my viewers, on what it means to be a Black person in America today and a product of four hundred years of racist ideology and policy making.”

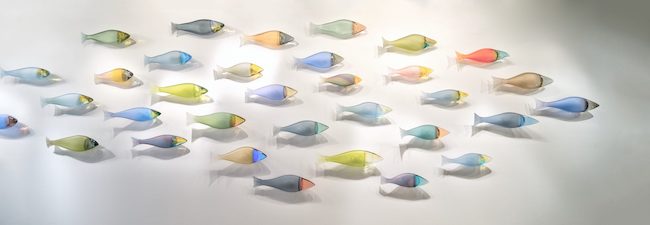

Dan Friday (American, Lummi Nation), Schaenexw (Salmon) Run, 2020. Blown and sculpted glass. Approx. 24 x 116 x 7 inches overall. Photo by Ian Lewis. Courtesy of the artist

Dan Friday is a member of the Lummi Nation of the Pacific Northwest coast, where many glassmakers congregated around the studio of Dale Chihuly. His great-grandfather was a totem pole carver whose work was featured in the 1962 World’s Fair. His own talents moved in a different direction. “When I saw glassmaking for the first time, I felt like I grew an inch! That is to say, a huge weight had been lifted off my shoulders. I finally knew what I wanted to be when I grew up.”

Friday went on to work with Chihuly and other artists in the Seattle glassmaking community. His Skanaexw (Salmon) Run (2022) is one of the largest installations in the show. Created specifically for the Wadsworth exhibition, the work is partly a return to his Lummi roots and pays homage to the migratory salmon fishing that was a major food source for the coastal tribes of North America, around which much of their lives and rituals were created. Now threatened by overfishing, both the salmon and the communities they supported are fading.

Friday’s bright wall work, in which each fish has its own glowing color scheme, is not naturalistic. The glass salmon have a distinctly modern feel, their surfaces, varying from translucent to transparent, matte to polished, and their abstracted shapes and uniform size suggest the taste and modernist charm of mid-century American designs. “With works like this I hope to raise awareness as to their fragile existence,” Friday says of the glass salmon. “I believe our fates are intertwined.”

Other artists in the show link themselves to the natural world through glass. Kiva Ford, who is well known for his scientific glass, created in collaboration with physicists and biologists for use in specific cutting-edge research, displays butterflies inside a lablike array of clear glass tubes and vessels. Nearby, the glassmaking team of Demetrius Theofanos and Dean Benson have created a wall display of delicate glass leaves in Flying Under the Sky (2022), also created for the exhibition. A series of intricately detailed insects, which seem about to fly or crawl off their perches in a glass case, were created by Wesley Fleming, who speaks of bringing “fantastic realism of the microcosmos to life in glass.”

Megan Stelljes, Neon Wallpaper III, 2022. Neon with sculpted glass. 36 x 60 x 5 inches. Courtesy of the artist, Arlington, WA

Many of the Wadsworth glassmakers work with climate change or extinction as part of their creative inspiration. Kelly O’Dell’s Long Before Us (2022) brings back to life a large, coiled ammonite, a species that went extinct 65 million years ago — “we learn from the past to be responsible in our future.” Others — Matteo Silvanio, Amber Cowan, Hannah Gibson — call attention to one of the primary social virtues of glass: it is one of the most recyclable of all human-created materials.

The focus of artists like Alex Ubatuba, Daisuke Takeuchi, Michael J. Schubert, Sidney Hutter, Tim Tate, and others in the show is largely to master glassmaking skills to create beautiful, mysterious objects that dazzle with color and form. “It can take a lifetime to master the craft of blown glass,” Ubatuba says, “and I plan to do so as long as I exist.”

The dignified design and subtle lighting of the Wadsworth installation manages to keep the diversity, frenetic variety, and colorist’s dream of this exhibition from being overwhelming, while highlighting the individual qualities of each piece and of the glass medium itself. Many new to glass will be delighted, but I get the sense, given all the many technical and historical references, an experienced member of the movement would get a lot more out of the show. It could have used, for example, a glossary of terms, especially one illustrated with real pieces of glass, to show just how remarkable so many of these creations really are.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in scholarly anthologies and has lectured at MIT, in New York, Milan, London, Los Angeles and many other venues. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than 100 projects, including theater, national television, and award-winning films. He is completing a novel set in the 1960s.

Tagged: Fired Up: Glass Today, Studio Glass Movement, glassmaking, peter-Walsh