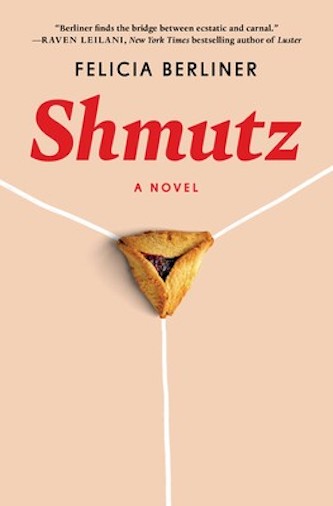

Book Review: “Shmutz: A Novel” — Hasidim in Heat

By Preston Gralla

A young Hasidic woman addicted to Internet porn? Oy vey, who knew?

Shmutz: A Novel by Felicia Berliner. 260 pp, Simon & Shuster. Hardcover, $27

Hasidic Jews – the most ultra-Orthodox of Jewish sects – have had their moment in the sun the last several years, with the internationally popular Israeli TV series Shtisel, the Netflix series Unorthodox, and The Rabbi Goes West by Cambridge filmmakers Gerald Peary and Amy Geller.

Hasidic Jews – the most ultra-Orthodox of Jewish sects – have had their moment in the sun the last several years, with the internationally popular Israeli TV series Shtisel, the Netflix series Unorthodox, and The Rabbi Goes West by Cambridge filmmakers Gerald Peary and Amy Geller.

But nothing you know, have seen or read about the Hasidim will prepare you for Shmutz, a filthy, funny novel about Raizl, an eighteen-year-old, unmarried Hasidic woman addicted to Internet porn. Hasidic women aren’t normally allowed to own or use computers. But Raizl attends college and helps support her family as an accountant, so an exception is made.

What starts innocently enough – Raizl Googling “G-d” and then the word “kiss” — soon leads to a full-on pornography habit. And this being a book in which much Yiddish is slung with much abandon, it also leads to full-on comedy.

Before we continue, an aside about the meaning of the Yiddish word shmutz. It translates as “dirt.” In my Jewish childhood it always meant a particular kind of dirt – the oily, nearly impossible-to-clean kind that builds up behind a young boy’s unwashed ears, or on delicate parts of his face. There’s only one way to clean it: A mother or aunt licks her thumb and uses it to rub the shmutz so hard, it feels as if your skin is being torn off. Squirm as you might, you’ll never escape until the shmutz is gone.

Poor Raizl. If only she could get rid of her shmutzy porn obsession that way. But she can’t and struggles to escape her addiction.

The very sound of Yiddish makes it a funny language. (Try saying shmegegge without laughing, or at least smiling.) It’s filthy as well. (Consider the infinite variations of its words for “penis” — schmuck, putz, shvantz and shmeckel among countless others. ) Berliner puts it to use with such hilarious, dirty intent that she rivals Philip Roth’s depiction of young Portnoy fulfilling his adolescent lust with a pulsating slab of raw liver. Just listen to Raizl’s eye-opening discovery during the early days of her addiction: “So this is what a woman does! Shaves her shmundie, takes a man in her mouth, eats without saying a blessing first.”

Raizl is sent to a therapist by her mother, not to conquer her addiction, of which her parents are unaware, but because Raizl refuses to visit the matchmaker to set up meetings with eligible Hasidic men. Raizl tells her therapist that she’s frightened of meeting them for several reasons, including being frightened of sex. Raizl also tells her about her addiction.

The therapy sessions propel the plot. It becomes clear to the reader, if not to Raizl, that her porn addiction and fear of meeting young men hint at something else: the wish of a sheltered young woman to be free of the constrictions a married Hasidic life would require. As part of her fight against those restrictions, she befriends a group of Goths at her college who see in her an outsider soulmate. Over time, the book, which starts out as pure comedy, deepens into something far more moving.

I won’t give away the resolution, other than to say that as in all good comedies, all’s well that ends well.

As a work of literature, Shmutz is a delight. But it raises a larger question: Does the book say anything about the world outside itself? Could such things happen to a young Hasidic woman, or is it just a convenient literary trope?

That question is made more complicated by Berliner’s portrayal of Raizl’s older brother as a pot-smoking semi-slacker and her younger brother as someone who takes far too much pleasure in dressing up in women’s clothing during Purim for a Hasidic family’s taste. Is all that simply a setup for a good novel? Or does it reflect the real world – to paraphrase Tolstoy, is it an instance in which “Happy families are all alike; every meshugenah family is meshugenah its own way”?

It’s a particularly difficult question for a secular Jew like me to answer. I have a built-in bias against the Hasidic community for its support of Netanyahu and the Israeli right wing, and for backing Trump and the U.S. right wing. There’s also its anti-vaccination sentiment that has made fighting COVID more difficult and led to finding polio virus in New York state’s wastewater.

The question is personal for me. I grew up just north of New York City in Rockland County’s Spring Valley, where Hasidim voted several years ago as a unified bloc to elect a majority of Hasidim men to the school board. They then gutted the public school system, which primarily serves poor minority students, while their own children attend tax-subsidized private yeshivas.

The book poses a basic question for me: Can I put my political feelings about the Hasidic community aside, and see each person in it as an individual with their own personal hopes, dreams and fears? When I see a young Hasidic woman, will I see the cardboard cutout I’ve seen before reading this novel, or will I see a fully formed human being, a Raizl or someone like her?

As a non-believer, I don’t put my faith in religion. I do, however, put my faith in literature. It’s a tribute to the power of this book to inhabit Raizl’s mind that I will try – and I hope, succeed – in seeing the humanity in every Hasid, as I try to do for everyone else. For secular Jews like me, sympathy and compassion are among the core tenets of Judaism. It took this book, shmutz and all, to remind me of them.

Preston Gralla has won a Massachusetts Arts Council Fiction Fellowship and had his short stories published in a number of literary magazines, including Michigan Quarterly Review and Pangyrus. His journalism has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Dallas Morning News, USA Today, and Boston Globe Sunday Magazine, among others, and he’s published nearly 50 books of nonfiction which have been translated into 20 languages.

A nice persuasive review, though could you tell us something about the author beside her name? Among other questions, is she/was she Hasidic?

A link to the author’s website.

A good question, and one that I tried to answer before writing the review. All I could find out are her academic accomplishments, which are impressive, and that she attended a yeshiva high school in Los Angeles. (I garnered that from her personal website that Bill links to in his comment.) However, I don’t know which yeshiva, or anything about her personal beliefs. Clearly, she knows the Hasidic world well, although that doesn’t mean she’s Hasidic.

Raizl comes from a tradition that strives for the individual to know God; that adheres to strict rules of behavior and a regimen of reminding one of God’s blessings through prayer and study. The study also tries to gain knowledge that guides one’s behavior to be in accord will God’s will.

The problem, in varying ways and degrees, for the individual is that just about everyone has to deal with emotions and thoughts that, by the guidelines of their tradition conflict with ideal behavior. Raizl’s predicament in this regard is magnified by the nature of her obsession with online porn….the indulgence in viewing prohibited sexual behavior. Sex desire is a powerful force that, like any powerful thing can be a strong influence for good, for evolution towards progress or, if abused is a powerful negative factor in that regard.

Unfortunately, the intellect is a weak means of dealing with emotions, the thoughts that arise from emotions and ultimately the resulting actions. The intellect can warn us and even prevent acting on unwanted emotions, but as a means to obliterate impulses that plague someone, the intellect is not comprehensive enough to root out those impulses. And the intellect cannot be a reliable guide to consistent holy behavior as the world presents an infinite medley of circumstances that each require nuanced reactions that qualify as actions that do no harm to the individual and the environment. Raizl navigates her life with one foot in her tradition that strives for Holiness with inadequate tools and another foot in the carnal, sinful world of on-line shmutz. The book gives no resolution to this predicament, and the ending begs for a follow up novel to see how Raizl fares in the future.