Book Review: Steve Reich’s “Conversations” — Something Special

By Jonathan Blumhofer

At its best, Steve Reich’s Conversations is illuminating and engaging, an honest discussion of the creative process by one of the major composers of our time.

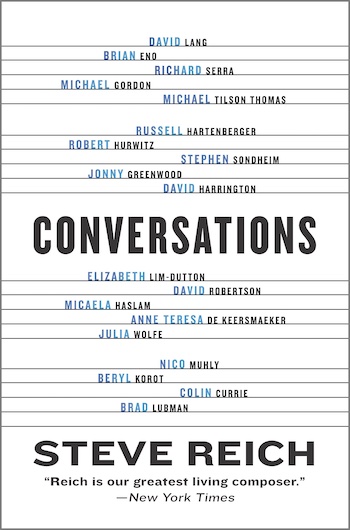

Conversations by Steve Reich. Hanover Square Press, 352 pages, $27.99.

“You have to be a megalomaniac in order to be a composer,” the composer Ralph Shapey once said. And one could be forgiven for thinking, off the bat, that Conversations, a 300-plus-page book of autogenic chats between Steve Reich and 19 friends and luminaries he’s influenced is the posthumous fulfillment of Shapey’s prophetic genius.

But that might be an unduly cynical, knee-jerk response. Reich is, after all, a significant composer and that to a degree no other classically trained figure — not even his contemporary, Philip Glass — can claim. He’s been a fixture in the contemporary music scene since the ’60s and, if his style and techniques remain somewhat controversial (particularly in academic circles), well, even there he’s making inroads (as a long chat with Professor David Lang from Yale University attests). In other words, Reich’s earned the benefit of the doubt.

And, in fact, Conversations isn’t the hagiographic, self-congratulatory pander-fest that, in lesser hands, it might have been. Sure, there’s some gushing, especially from performers: violinist Elizabeth Lim-Dutton loses no opportunity to praise Reich and express gratitude for the opportunity to play and premiere his music. Others, like Lang and vocalist Micaela Haslam, suggest they’re similarly in his debt. That said, all three have long working relationships with the composer and the insights they bring from those experiences (Lim-Dutton playing Music for 18 Musicians, for instance, or Haslam learning Tehilim) largely compensate for any other excesses.

The overall structure of the book is more straightforward than that of its obvious forebear, Igor Stravinsky’s eponymous 1959 publication (Reich acknowledges his debt to the older work in his Preface). That volume was notable for its candor as well as a good bit of name-dropping and the subtle political mission of reinforcing Stravinsky’s avant-garde bona fides in the aftermath of World War II. As guided by the composer’s amanuensis, Robert Craft, it followed a somewhat discursive path.

My, how times have changed.

Reich’s Conversations is the opposite, basically tracing his career chronologically (he does a good job, making sure just about each discussion doesn’t wander too far off-track), touching on all the major (and some minor) works, as well as the composer’s recorded career and his Jewish faith. Throughout, it carries its baggage lightly: there’s no need to settle scores or prove points; in these pages, Reich is perfectly comfortable in his own skin.

The most familiar materials are covered early on, in dialogues about the development and impact of the ’60s-era “phase music” compositions Reich has with Lang, Brian Eno, and Michael Gordon. If Reich aficionados (and casual acquaintances) may be acquainted with their broad strokes (experiments with tape loops, live performance with/against taped recordings, and the like), a chat with Richard Serra provides a welcome bit of cross-disciplinary context, anchoring the musical developments of the period in a broader, thriving, postwar Manhattan arts scene.

Also striking is a long interview with Michael Tilson Thomas, who, in his apprentice years with the Boston Symphony, led Reich’s Four Organs in a legendary 1973 performance at Carnegie Hall that provoked a near-riot. That occasion (“a really startling cultural event,” as MTT labels it with gleeful understatement) and the lead-up to it are thoroughly discussed here, as is the conductor’s larger experience with Reich’s music (he’s recorded nearly all of the orchestral works).

By far the most unexpected inclusion in the book is the transcription of an evening-long conversation (moderated by John Schaefer) with Stephen Sondheim. What connections — besides the claim to each having studied with a leading avant-gardeist (Sondheim with Milton Babbitt, Reich with Luciano Berio) — do these artistic giants share? I won’t spoil the surprise but will just say: more than a little, as you’ll discover reading this most enlightening of chapters.

While the idiosyncratic connections — particularly Reich holding court with Sondheim or talking shop with Radiohead’s Johnny Greenwood — mark some of Conversations’ narrative high points, there’s a subtler theme of contraries working in tandem that unfolds as one proceeds through the book. Perhaps the most significant of these involves Reich’s long relationship with technology.

We get glimpses of his working methods and how they’ve developed over the years: the physical splicing of tape loops in the ’60s; layering guitars through keyboard samplers while writing Electric Counterpoint in the ’80s; the clutter of wires and audiovisual equipment that was part of the process of writing The Cave with wife (and acclaimed video artist) Beryl Korot in the ’90s, and so on. A throwaway observation to conductor Brad Lubman about listening to pieces-in-progress via MIDI playback will surely resonate with every composer over a certain age who picks up this book.

At the same time, there’s a decided emphasis on the glories of live performance. It’s here, we’re reminded (and particularly in pieces like Music for 18 Musicians and Drumming), that the humanity of Reich’s music really emerges. In his world, technology is an aid — and not infrequently a means to an expressive end, too. Yet it’s conveyed again and again that, by itself, the Machine is no substitute for the visceral, emotional punch only found in good old-fashioned acoustic music-making.

And if that’s not anachronistic enough (particularly coming from one of the leaders of the Minimalist Revolution), surely Reich’s love of all things Medieval and Renaissance — Josquin, Machaut, organum, et al. — is.

Steve Reich — he will be 86 next month, and the composer sounds as fresh, generous, spry, and curious as ever. Photo: Jeffrey Herman

Actually, neither are: there was a communal aspect to Minimalism all along (as Glass and Terry Riley might also attest), and there’s nothing derivative or outlandish about Reich’s fascination with or employment of isorhythm and mensuration canons in his music. (On the other end of the stylistic spectrum, György Ligeti was contemporaneously engrossed by many of these same procedures. On an unrelated note, he even wrote a two-piano piece called “Selbstportrait mit Reich und Riley” in 1976.) Indeed, this enthusiasm for music written up through the time of Bach and picking up again with Debussy and Stravinsky explains a lot about Reich’s particular voice. And to hear (or, rather, read) him articulate the way that influence has shaped specific pieces, from Four Organs to Traveler’s Prayer, is clarifying.

The one thing we haven’t got in Conversations is any sort of contrarian (or, really, just critical) viewpoint on tap. That’s not necessarily surprising — or, in at least one regard, a bad thing. Without anyone to tell you that neither The Desert Music nor The Cave are generally regarded as among Reich’s stronger efforts; or that, say, in veering so closely to the techniques of Different Trains, WTC 9/11 comes off more imitative than fresh, one can at least think about these pieces with minimal bias. Given how consensus for a composer as famous and controversial as Reich will invariably shift, that’s a valuable exercise. But it does mean that certain touchier subjects — like the periodic complaints of cultural appropriation that crop up regarding certain of Reich’s works (like the West African-inspired Drumming) — aren’t investigated.

Even so, the book as it stands is illuminating and engaging. In fact, as Conversations reaches its denouement in chats with Korot, Lubman, Nico Muhly, and Colin Currie, it becomes more: an honest discussion of the creative process by one of the major composers of our times. That’s something special.

Through it all, Reich, who’ll be 86 next month, sounds fresh, generous, spry, and curious as ever. More power to him. If Shapey was right and this is megalomania working its magic, well, perhaps more of us should aim to be composers after all.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Hanover Square Press, Jonathan Blumhofer