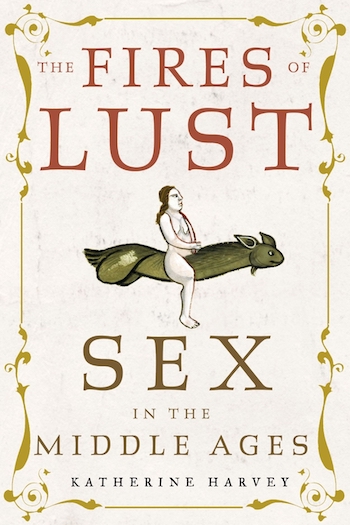

Book Review: “The Fires of Lust” — Copulation in the Middle Ages

By Thomas Filbin

Historian Katherine Harvey’s well-researched and lively book shows that in the Middle Ages lust had its way. Big time.

The Fires of Lust: Sex in the Middle Ages by Katherine Harvey. Reaktion Books. 296 pp. $27.50.

Every generation likes to imagine it discovered the joys of sex. Their parents might have indulged, but it was passionless employment for the sake of procreation. The Victorians put up considerable barriers against coitus, believing that buttons, buckles, and corsets would frustrate physical intimacy — lovers were supposed to be kept at bay until matrimony. The strategy’s success was … problematic. So, what of the Middle Ages? In those days they must have known how to squash desires of the flesh? Medieval historian Katherine Harvey concludes in her well-researched and lively book that, like today, lust, in all its myriad forms, had its way. Big time.

Every generation likes to imagine it discovered the joys of sex. Their parents might have indulged, but it was passionless employment for the sake of procreation. The Victorians put up considerable barriers against coitus, believing that buttons, buckles, and corsets would frustrate physical intimacy — lovers were supposed to be kept at bay until matrimony. The strategy’s success was … problematic. So, what of the Middle Ages? In those days they must have known how to squash desires of the flesh? Medieval historian Katherine Harvey concludes in her well-researched and lively book that, like today, lust, in all its myriad forms, had its way. Big time.

Garden variety lust is well surveyed because it occurs in marriage as well as before. As a rule, medieval people married young — it was the only acceptable way to channel urges. Is it any surprise that the double standard was up and running? Girls were expected to be virgins up until marriage, while boys, well, boys will be boys. Courtship was a family matter: the wealthy and titled wanted their children to marry into the same class but, even among the common folk, clan approval was vital. That meant that others had a say in who you were going to have sex with, not you alone. A late 15th-century Londoner, Margery Sheppard, clearly articulated the restriction: “I will do as my father will have me; I will never have none against my father’s will.”

Attraction was not unimportant, of course. Breasts were featured performers. Interestingly enough, men of the time preferred small, firm breasts. The French poet Eustache Deschamps (1346-1406) favored tight dresses with wide necklines that pushed the bosom and throat forward. Harvey cites a German poem in which a stepmother advises her daughter on how to seduce a man: leave her bodice unlaced, thus “causing his courage to rise” (among other things!). Large and loose breasts suggested ample sexual experience and that impression might damage a single woman’s reputation. A Spanish text insists that moist armpits were a desirable feminine feature. Of course, the ladies had their preferences. Tall, strong men with fair skin were generally thought to be superior. Body hair and a mane were marks of masculinity (Oh, Fabio, you missed your moment). Large and hard penises were preferred because they were signs of abundant sperm.

Celibacy requirements for the clergy were in force. They were not only barred from marriage but encouraged to remain chaste. Was it Bertrand Russell who opined that, of all the sexual possibilities, the most perverse was abstinence? Harvey provides evidence that priestly chastity was honored as much in the breach as the observance. Some priests bribed bishops to turn a blind eye to their behavior. In 1072 the Archbishop of Rouen had to flee a synod when the assembled clerics stoned him because he attempted to take away their concubines. Living up to the no-sex standard was difficult. The popular suspicion was that priests, having no wives of their own, copulated with the wives of others. When a woman complained of her husband’s impotence to St. Hugh, Bishop of Lincoln, he allegedly quipped, “Let us make him a priest and the power will immediately be restored to him.”

The church (then or now) hasn’t dared to admit just how blatantly ineffective it is to deny basic human needs and inclinations. Harvey notes that “few flouted the rules quite so blatantly as Jean de Heinsberg, Bishop of Liège (1419-1456), who reportedly had 65 children.” She adds that, at the turn of the 16th century, somewhere around 45 to 60 percent of the clergy in Brabant were fined for sexual offenses at some point in their career. Despite the prohibition on clerical marriage, many priests continued to have sexual relationships and even formed long-term partnerships. Monks also enjoyed the intimate company of women. One, the prior of Sant Joan les Fonts, kept a woman named Ermesenda and refused to comply when the bishop ordered that she must go. Harvey notes that “According to the other monks, the elderly pair spent much of their time reading in the kitchen. This relationship was clearly about much more than sex: there is something rather touching about this image of a long-term couple keeping each other company in their old age.”

Fornication was forbidden, though tolerated given what all accepted as the wayward passions of youth. Adultery was a more serious offense, calling for public condemnation and public whippings. Forms of retribution could be over-the-top sadistic: one punishment associated with adultery demanded that the errant couple be stripped naked, bound together around their genitals, and then flogged as they were paraded through the streets.

Fornication, adultery, and incest were plainly off limits, but bestiality was the worst. In Castile Spain both the human and the animal involved in such acts could be punished by death. (The demise of the poor beast eradicated the memory of the sin.) In Venice, a man was accused of bestiality, but in his defense claimed that he had been unable to have relations with a woman or even masturbate. “The judge … required two prostitutes to do ‘numerous experiments’ in order to test (his) claims, … (and this) medical evidence meant that he escaped the death penalty.” Harvey drily tells us that the man was branded, beaten, and lost a hand. The fate of the goat is unknown.

Prostitution, the oldest profession, was subject to condemnation mitigated by understanding. The church was concerned that, because a woman’s clients were not always known, it was impossible to determine if some of the transactions were adulterous. On the other hand, the sex worker’s wages were earned through bodily labor so she was allowed to keep them. A distinction was also made between a woman who had sex for pleasure and ones who did so for financial need and desperation. The latter could be granted forgiveness and do penance. Mary Magdalene, in most scholarly opinions, was a repentant prostitute who became a follower of Jesus. Pope Innocent III asserted that men who married prostitutes in order to reform them were doing good acts that counted toward remission of their own sins. Even in medieval times it was acknowledged that sex work was often a last resort, not a career choice.

A picture of sexual satisfaction in the Middle Ages.

As far as same-gender relationships are concerned, they were forbidden and could be punished by death. Still, same-sex attractions and persons born as one gender who dressed and acted as another were not uncommon. Rolandino Ronchaia (in 14th-century Venice) might be described as intersex, a man who, because of a hormonal imbalance, was more feminine than masculine. He was socialized as a man, even though he had breasts and it was generally agreed that he looked more female than he did male. He eventually dressed as a woman, was known as Rolandina, and had sex with men, hiding as much of himself as would be recognized and allowing penetration so the male partner was often deceived and thought him a woman. This was not a survival strategy that could endure, however, and he was tried as a sodomite and burnt to death. An Englishman named John Rykener in the late 14th century sometimes went by the name Eleanor, lived as a woman for long periods, and had sex with men and women, including priests and nuns. Today he might be considered bisexual, given his activity, but nonbinary, trans, or gender fluid as to his identity.

In her conclusion, Harvey admits that written records about sex in the Middle Ages focused on the sensational rather than the commonplace. As in the contemporary media, the titillating garners the most ink. Most marriages were happy and priests who observed their vows did not make news. The historian cautions that her account of sexual crimes and punishments is somewhat bleaker than the truth. “Just like today,” she writes, “medieval sexual experiences could be horrifically violent or extremely funny, but most fell somewhere in between.” What’s more, many of the period’s representations of sex in the popular culture are suspicious, often not grounded in fact. When it came to copulation, spinning a good yarn was preferred. Harvey’s The Fires of Lust is part of that venerable tradition. She has written an entertaining but thoughtful study, descriptive without becoming didactic or pedantic. Her message is, depending on your perspective, reassuring: “then” is not all that different from “now” — when it comes to sex, plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

Thomas Filbin is a book critic whose work has appeared in the New York Times Book Review, Boston Sunday Globe, and Hudson Review.