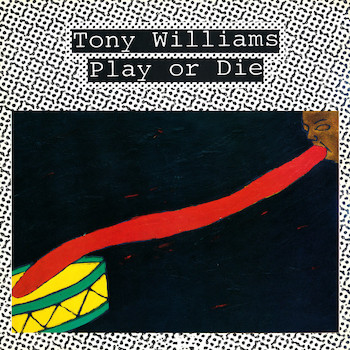

Jazz Album Review: Tony Williams’s “Play or Die” Gets Full Release, 40 Years On

By Steve Elman

The shadow of Weather Report looms over this groove session of consonant harmonies, the only documentation of a short-lived band that should have had the chance to burn more brightly.

You always hope for a long-buried archive to yield untold riches when it’s finally unearthed. Sometimes your hopes are rewarded. Sometimes what you get is a handful of gems, a few valuable coins, and a collection of historic trinkets.

You always hope for a long-buried archive to yield untold riches when it’s finally unearthed. Sometimes your hopes are rewarded. Sometimes what you get is a handful of gems, a few valuable coins, and a collection of historic trinkets.

It’s the second result with Play or Die, the only documentation of Tony Williams’s last power trio, recorded in February 1980. The original release had extremely limited distribution and almost immediately disappeared. It has finally come to the wider market in the past month thanks to Germany’s M. I. G. Music.

Not that this recording is not welcome – and Williams fans will be delighted by his ever-fertile drum accompaniment, and two examples of his superb soloing. But if anyone hopes for the blazing fire of Emergency!, the debut of Williams’s still-iconic band Lifetime, they will not find it here.

The title of this album suggests a hell-bent-for-leather go-for-broke workout. Instead, this is primarily a groove session of consonant harmonies and agreeable playing, with Tom Grant colorfully decorating the music with keyboards and synth, and Patrick O’Hearn providing a steady anchor on electric bass. Of course, Williams is the reason you keep listening, because whatever he plays is fascinating. But the shadow of Weather Report looms large over the whole proceeding, maybe to its detriment.

It’s useful to think of the context. Three years before the Play or Die sessions, in 1977, Weather Report recorded and released Heavy Weather, the only one of the band’s releases to reach platinum sales, and the LP that introduced “Birdland,” which was ubiquitous on jazz radio that year and became the band’s signature tune. Their followup, Mr. Gone, came out in 1978, and it, too, sold very well, with “River People,” another tune of ear-tickling grooves, getting the most radio play.

Williams himself may have collected some ideas from WR”s Joe Zawinul, since he participated in two of the tracks on Mr. Gone, the title tune and Jaco Pastorius’s “Punk Jazz,” where he really shines.

A new jazz group in 1980 could hardly avoid the biggest success story of the past three years, a success story that Williams had seen first-hand. What Grant and O’Hearn took from Weather Report’s track record was that concept of the tuneful groove, and bassist O’Hearn, who is most responsible for the foundation of the first three tunes on Play or Die, served up the right kind of lines over which good solos can be built.

Unfortunately, those bass lines are the beginnings and ends of the structures in the first 28 minutes of the CD. There are no alternate themes introduced to enrich the foundations of “The Big Man,” “Beach Ball Tango,” and “Jam Tune,” and the harmonic shifts are minimal. Grant does the lion’s share of the harmonic work and he makes no attempt to stretch his solos beyond the given harmonies into more challenging territory. He does evoke Joe Zawinul’s keyboard work in the first strokes of “The Big Man,” but he simply does not have Zawinul’s Ellington-like imagination and understanding of the vast colors available to the keyboard “orchestrator” which made Weather Report’s music so kaleidoscopic.

However, “Beach Ball Tango” has one of the two drum solos on the CD, set up over a strong vamp, and Williams builds considerable power here, making this the most satisfying of the three openers.

However, “Beach Ball Tango” has one of the two drum solos on the CD, set up over a strong vamp, and Williams builds considerable power here, making this the most satisfying of the three openers.

With the last two tunes, both Williams compositions that had been previously recorded, the CD goes into richer territory.

“Para Oriente” began life the year before. Williams played it electrically in March 1979 in his one-shot Trio of Doom (with Jaco Pastorius and John McLaughlin) and acoustically in July 1979 with Herbie Hancock’s VSOP band. The tune was remarkably resilient, working well and funkily in both contexts. But in both previous outings (neither of which had been released in 1980), Williams was working cooperatively with others, and both of those earlier live recordings have loose, spontaneous realizations, for better or worse. This studio version gives more than a hint of how Williams wanted it to sound.

The setup is ear-catching, with Grant choosing some tight electric piano chords and a repeated high note, like a sonar signal. O’Hearn gets his one bass solo of the date, which builds nicely and segues smoothly from rockish feel to swing tempo; however – and no slight intended – he is not Jaco Pastorius. Grant’s electric piano solo sounds like a first take, and he should have had the chance to really dig into the music.

Comparing it with the Trio of Doom version from nearly a year before illustrates what is missing. The difference, quite simply, is guitarist John McLaughlin’s understanding of harmony. In the earlier version, McLaughlin augments each of Williams’s basic chords with higher notes that add density and interest to the harmonic structure. If Williams had added them to his chords when the tune was recorded in the Play or Die sessions, they would have given it a spiky punch and possibly inspired Grant to something more substantive.

In Grant’s notes to the new issue of Play or Die, he calls the sessions “grueling and fast,” which suggests that the band was working on a tight schedule. This track suggests that the whole session could have been much better if the trio only had had the time.

The surprise gem of the album is the closer – a reprise of one of Williams’s neo-dada songs with vocal, “There Comes a Time,” which dates from the 1971 Tony Williams Lifetime release Ego. In Williams’s vocals on earlier releases, his thin tenor has a shaky relationship to pitch: it is either obscured by poor recording (as on Emergency!) or intentional studio tinkering (as on Ego). Play or Die has his best vocal on record, and Williams has clearly learned much about singing in ten years. He is on pitch, and sings the words with conviction, even the enigmatic lines, “I love you more when it’s over” and “I love you more when you’re spiteful.” This version is also more thoughtfully structured than the original, with a drum solo over a clean vamp of electric piano chords, which snaps and pops beautifully and leads to a satisfying stop.

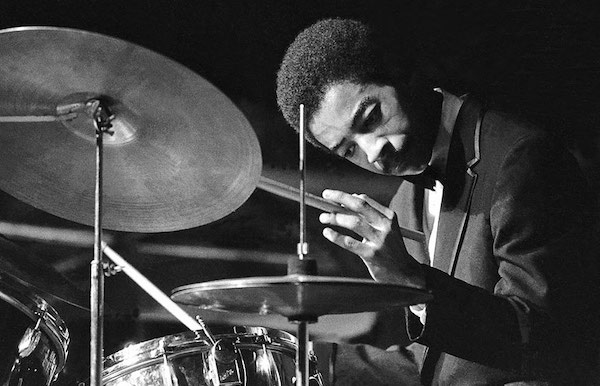

Drummer Tony Williams in action. Photo: Jan Persson & CDJ.

This version also illuminates two other versions of the tune, recorded by Williams’s disciple Cindy Blackman Santana on her debut CD Another Lifetime (2010, Four Quarters) and with the cooperative band Spectrum Road, on their eponymous CD (2012, Palmetto). It seemed when Blackman Santana’s CD appeared that she had come up with a strong new arrangement of the tune, but now it’s clear that she had access to the original release of Play or Die, and built her arrangement on what she heard there — and then brought it along when she became part of Spectrum Road. Now we can hear it too, and we can say without reservation that this version is The One to Have.

Many of Tony Williams’s releases seem in retrospect to be unfinished business, whether because his ideas were too idiosyncratic to be realized fully or too advanced to be appreciated fully in their time. This is yet another example, but it is a genuine rediscovery, and it deserves a respectful full-volume hearing; at medium volume, it will serve as pleasant background and challenge no one’s thinking. There’s no question this group turned the amps up when they played live, so, when listening to Play or Die, at least once you should take the advice Williams gave in bold type on the back cover of his 1970 CD, Turn it Over: Play it Loud.

More

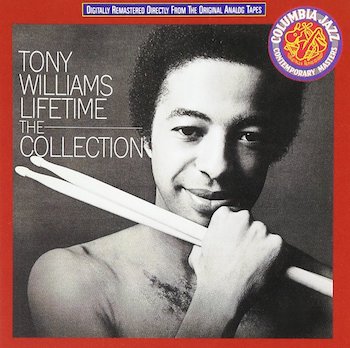

So much of this post looks back to the Tony Williams Lifetime of 1969 / 70 and its many tribute / successor groups that a companion post on the original trio and its impact seemed appropriate, even inevitable. Here it is.

Credit where it’s due: Curt Bianchi’s encyclopedic “Weather Report: the Annotated Discography” provided some valuable insight (and good anecdotes) about Tony Williams’s participation in the Mr. Gone sessions.

Steve Elman’s more than four decades in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host on WBUR in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, 13 years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB.

Tagged: M.I.G Music, Play or Die, Steve Elman, Tony Williams