Doc Talk: Three Portraits of Artists — One as a Young Woman and Two as Old Men

By Peter Keough

Three recent documentaries explore the worlds of three masters of disparate but complementary art forms: photography and cinema, sculpture and painting, and toilets.

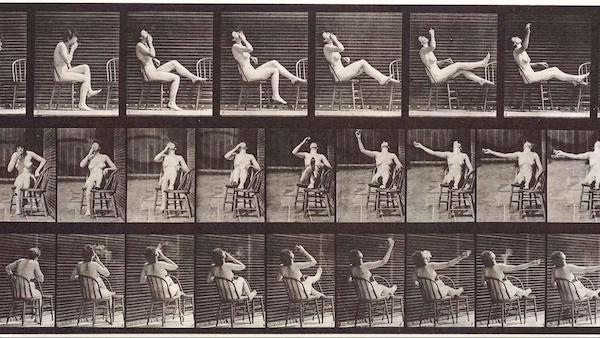

A scene from Exposing Muybridge.

Perhaps in the spirit of one word being worth a thousand pictures, director Marc Shaffer asks some of his expert talking heads to choose an adjective to describe the subject of his engaging and insightful Exposing Muybridge (2021; available on demand –go here.)

“Daring,” says University of Chicago professor emeritus of film history Thomas Gunning about the 19th-century photographer and motion picture pioneer. “I almost said crazy.”

“Duplicitous,” offers Rebecca Gowers, author of The Scoundrel Harry Larkyns and His Pitiless Killing by the Photographer Eadweard Muybridge (2020). Her book is about one of the more infamous scandals in Muybridge’s eventful life in which he shot his young wife’s lover but was acquitted of the murder by a sympathetic all-male jury.

The effervescent actor and Muybridge collector Gary Oldman gets to slip in more than his share of modifiers. “Temperamental, volatile,” he says. “Sharp, talented.” Holding up a photo of a bearded, wild-eyed Muybridge huddled under a giant redwood, he adds, “For an actor, if I were to play Muybridge, that’s gold dust.”

Muybridge seems to have been something of an actor himself, in search of a role to play, his identity protean. Born in 1830 in Surrey, England (he died in 1904 at 74), as a young man he told his grandmother, “I am going to make a name for myself. If I fail you will never hear from me again.” He emigrated to America and soon achieved that goal — literally — changing his name several times and settling on the eccentric final version in 1865.

By that time he had worked as a bookseller before venturing into the daguerreotype trade. As a landscape photographer he visited Yosemite and other wild locations, creating sublime images in which towering monoliths dwarf human figures like in Chinese paintings or Caspar David Friedrich canvases.

His work drew the eye of the US government, who sent him in 1868 to the newly purchased Alaska territory, where he photographed the indigenous Tlinkit people, and then in 1873 to California to capture the army’s response to an uprising of the native Modoc tribe. Richard Jackson, a Tlinkit clan leader and activist, examines a group portrait of his ancestors made by Muybridge and describes how the image moves him as an artifact linking him to his roots. But photographic experts analyze a Muybridge picture titled A Modoc brave on the Warpath and determine that it is a staged reenactment. Thus Muybridge’s earlier work demonstrates photography as a medium for recording historical reality and perpetrating historical fraud.

But Muybridge is best known for the animal motion studies, and Shaffer indulges in his own staged reenactments in demonstrating the process by which these were accomplished. Hired by the railroad mogul and keen equestrian Leland Stanford in 1872 to prove that a galloping horse will at some point have all four hooves off the ground, Muybridge set up a series of cameras to capture the action and broke it down into a sequence of split second images. He not only proved Stanford’s premise but pursued further such studies. These he presented to audiences by animating the sequences with a device called the zoopraxiscope — a landmark in the development of motion picture technology that has probably now reached its apotheosis on social media as the GIF.

A scene from 2016’s Eva Hesse.

While Muybridge employed photographic methods to delve into the nuts and bolts of animal locomotion, Eva Hesse fashioned nuts and bolts and other commonplace materials into minimalist sculptures expressing an antic and troubled soul. Marcie Begleiter’s stolid and engaging Eva Hesse (2016; available on Kino here) provides an introduction to her meteoric life and career (she died of a brain tumor in 1970 at 34).

But the film’s style and approach, given the determinedly unconventional subject, is sometimes disappointingly conventional, consisting of talking heads, archival footage and stills, brief split screen glimpses of artworks, and voice-over recitations of correspondence (Hesse’s letters to and from lifelong friend Sol LeWitt are especially poignant and illuminating).

The film begins with a montage of encomiums from experts and Hesse’s friends, associates, and family members and the artist’s own gung-ho self-assessments and nagging self-doubts (read by a surprisingly insipid Selma Blair), a device that, as seen in Shaffer’s film, is becoming a kind of documentary cliché. One interviewee claims that Hesse is “One of the 20th century’s greatest artists.” Another, with less hyperbole, says that Hesse’s life and art merged, that “she wasn’t just manipulating material, she was the material.”

That life was replete with trauma and ambition. She was born to a Jewish family in Hamburg in 1936. Her beloved father managed to shuffle her and her sister off to safety from the encroaching Nazi genocide in 1938 in one of the last Kindertransport trains to the Netherlands. There she was sheltered in a Catholic home (where she was punished for bedwetting) before her father and mother escaped and they all found refuge in New York. But almost every one else in the family perished in the Holocaust. Eva’s mother never recovered from the trauma and committed suicide in 1946. Eva’s schoolmates taunted her about the tragedy.

Nonetheless, her creative, ardent spirit prevailed and found an outlet in painting and drawing (though downplayed in the film, these early works possess a delicate, exhilarating inventiveness, a kind of link between Paul Klee and John Lurie). It was the right time and place for a profession in the arts — New York in the early ’60s was in the midst of a cultural renaissance — demonstrated by Begleiter’s flurry of images of Jasper Johns, Edward Albee, and Susan Sontag.

Unfortunately almost all of those in the visual arts were men. Hesse married one of them — the heavy-drinking, up and coming young sculptor Tom Doyle. When he was invited to a residency in Kettwig Germany in 1964, she accompanied him despite her anxiety about returning to the country that almost murdered her and her family not quite 25 years before.

Her stay there was marked by nightmares of pursuit and persecution (rendered by Begleiter in dour animations), a crumbling marriage, isolation, and a rebirth in creativity. Her studio was housed in an abandoned textile mill and, drawing on discarded machine parts, tools, and other industrial materials, she turned to sculpture, creating in 1965 one of her first major works – Ringaround Arosie, a conical, pink areolaed subversive confection. She had, so the film asserts, reinvented minimalism — no longer the stark, rigid, juiceless monoliths of the macho masters, this was minimalism with a human soul, with a bracing sexuality, a feminine subversiveness, and a dash of madness.

Back in New York she and her friends shopped at the Canal Street market in Lower Manhattan to buy secondhand hardware, which she would transform into audacious installations such as ceiling-hung udderlike bladders and festoons of plaster ropes. These creations brought her recognition, gallery shows, and critical praise.

Meanwhile, though, her personal life was crumbling — her marriage broke up, her father died. Then she had a revelation — fiberglass! She immersed herself in this new medium, creating gossamer-like assemblages of squashed, tipsy geometric shapes and translucent boxes pierced with thousands of plastic straws. Overcoming the patriarchal bias, she became “one of the boys,” as one of her collaborators puts it, and was on the brink of superstardom. But then she developed headaches that got worse and did not go away…

Did Hesse’s immersion in her toxic materials contribute to the brain tumor that killed her? The movie is undecided on this, but she did know that the materials themselves (the fiberglass excepted) were ephemeral. Many of the sculptures have since deteriorated, but some art critics, such as Arthur Danto, have claimed that in so doing they have only achieved a different beauty. When she was told that some of her works would not last long, a friend recalls, Hesse said, “Let them [the museums and collectors] worry about it — I want what the effect is now.”

A scene from Potty Town.

Like Hesse, Hank Robar, an octogenarian Potsdam, New York, realtor, also creates art objects from discarded plumbing fixtures. Both follow in the tradition of Marcel Duchamp, who, as Morgan Elliott points out in his documentary Potty Town (2022; now available online here), scandalized the art world by entering a urinal in an art exhibit in 1917.

But Robar did not get into the art business out of any aesthetic calling. It was more like petulant revenge. Two decades before, the town zoning board had refused to permit him to sell one of his properties to Dunkin’ Donuts. Bad blood ensued. Robar began decorating his lots and premises with toilets — dozens of them — outraging house-proud neighbors. As the town fought back with targeted legislation, Robar hired a lawyer who argued that the porcelain potties were, in fact, art. And Robar started to think the same, garnishing the bowls with plastic flowers and funny signs. He sued for $7 million and the town settled for an undisclosed sum with the promise to leave Robar’s art works undisturbed.

Elliott follows the story with a wry, absurdist irony reminiscent of early Errol Morris films like Gates of Heaven (1978) and Vernon, Florida (1981), ending with a local band performing a song that asks the immortal question, “Is That a Toilet or Is It Art?”

Peter Keough writes about film and other topics and has contributed to numerous publications. He had been the film editor of the Boston Phoenix from 1989 to its demise in 2013 and has edited three books on film, most recently For Kids of All Ages: The National Society of Film Critics on Children’s Movies (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).

Tagged: documentary, Eva Hesse, Exposing Muybridge, Marc Shaffer, Marcie Begleiter, Morgan Elliott

This article is fascinating, thank you! I wonder if you saw the new movie “Nope” which fictionally claims the the protagonists’ great-great grandfather was the jockey on Muybridge’s horse. I like this quote from the Times (7/22) that has ties to your story here:

“Muybridge is the guiding spirit of “Nope,” in which the siblings, along with an electronics-store employee (Brandon Perea) and a cinematographer (Michael Wincott), try to snap a photo of an elusive extraterrestrial presence. They’re attempting to capture an impossible shot, with a subject that, like Muybridge’s horses, is too fast to pin down. And since the U.F.O. scrambles all the electricity in its path, they have to innovate with analog technology, as Muybridge did. (Muybridge was also a chronicler of the American West.)